In recent years, the US and other Western economies have grown increasingly alarmed at their dependence on Chinese-tied supply lines, stoked by the US-China trade war launched five years ago by ex-president Donald Trump and accentuated by disruptions tied to the coronavirus pandemic. The realisation has prompted calls to accelerate coordination among USMCA member countries.

“Policymakers are turning in earnest to worry a lot more about the resiliency and security of supply chains,” said Simon Kennedy, Canada’s deputy minister of innovation, science and economic development, at the Brookings event. “The pandemic really brought home this issue.”

Supply-chain concerns have sharpened the economic rivalry between Washington and Beijing, adding to the many other irritants as relations have soured.

“We realised [that] if we can’t get chips, we can’t get cars,” said Jayme White, deputy US Trade Representative. “We have to win the race for the future.”

Of the relatively few export manufacturing sectors that have witnessed a significant shift away from China in recent years, notably semiconductors, most have moved to Southeast Asia, especially Vietnam.

Between 2018 and 2021, as China’s share of US factory imports fell by four percentage points, American imports from other Asian developing countries rose by an equivalent amount, with Vietnam leading the pack.

Not surprisingly, however, many Chinese firms quickly shifted gears, supplying Vietnam and others for onward shipment to North America. In 2017, China accounted for 10.8 per cent of the US-imported content in Vietnam’s exports. By 2021, that figure nearly doubled to 20.3 per cent.

Although some American lawmakers and corporations call for a US-China “decoupling” of trade flows, this is easier said than done, writes Dollar, a former Treasury official with the US Embassy in Beijing – whether from China to North America, from China to other Asian countries, or to less complex supply chains.

Bureaucracy, inadequate coordination and higher costs have impeded broad-based nearshoring to the US, Canada and Mexico, experts said on Tuesday, even as China retains strengths and economic advantages developed over decades that are difficult to replicate.

And while some supply chains are getting shorter, others are getting longer, the report said. Meanwhile, China has better logistics, human capital, specialisation and intellectual property protection than many of its rivals – including Southeast Asian countries, India and Mexico.

“China stands out with relatively good IPR protection,” said Dollar, a former World Bank official. “At the other end of the spectrum, Mexico is rather poor. This hampers the potential for significant near-shoring back to North America.”

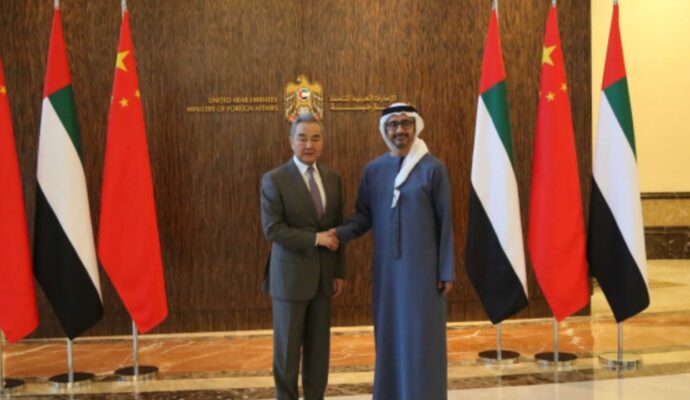

Growing distrust of China in Washington and other Western capitals has also spurred national security concerns, tied to live-fire exercises after then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August and to Beijing’s support for Moscow after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a year ago.

Washington worries that China, as the world’s largest manufacturer and trading nation, has inordinate leverage over several vital strategic commodities, from rare- earths processing and batteries to medical devices and pharmaceuticals.

“China’s potential as a disrupter cannot be ignored,” wrote Bradley Martin, director of the Rand National Security Supply Chain Institute and another co-author. But he added that Beijing was not without its own vulnerabilities.

“Just as China can use its dominance in parts of critical supply chains, the US also has leverage,” particularly in semiconductors, chip-making equipment and other advanced technologies, said Martin. “The intersection between very complex supply chains and national security vulnerability is stronger than it has ever been.”