Good morning. It’s been an eventful week, with a power-packed but chaotic AI Impact Summit in New Delhi. While countries and companies have announced big plans and deals to make the best use of the technology at the gathering, we will have to wait to see how much of this translates into real action. On the capital’s streets, where people have been subjected to hours of traffic delays, there is palpable relief that the summit is coming to an end.

My colleague Andres Schipani and I will be answering all your questions about India’s trade deal, geopolitics, and economy on Friday, February 27, at 5.30PM IST in our Ask an Expert series. Send us your questions here.

A new old plan

The union cabinet has approved a Rs1tn ($11bn) fund to improve urban infrastructure. Called the Urban Challenge Fund, the move signals the government’s intent to shift infrastructure funding away from a grant-based approach to a more market-led model. Projects approved under the scheme must raise at least 50 per cent funding from the market, with the government contributing only a quarter of the project value.

This is expected to translate into Rs4tn of investment over the next five years, helping make Indian cities “resilient, productive, inclusive and climate-responsive” so they can be the key drivers in the next phase of the country’s economic growth. The proposal was first announced more than a year ago in finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s 2025 budget, but consultations with various state governments took longer than expected.

There is no doubt India’s infrastructure needs a massive reboot. Decades of poor planning, poor execution and poor maintenance have rendered most cities challenging, and often dangerous, to navigate. Public frustration has reached a tipping point, with widespread outrage in recent weeks triggered by harrowing accounts of young people falling to their deaths in unmarked construction pits. Tired of dealing with constantly dug-up roads, collapsing bridges and contaminated water, Indian taxpayers are belatedly, but rightly, demanding some accountability for their tax money.

The government’s bet is that market funding for these projects will, in effect, multiply its budgetary allocation fourfold. But even this barely scratches the surface. A 2022 World Bank report estimated that India needed to invest $840bn on urban infrastructure and municipal services in the 15 years to 2036. That is more than Rs4tn a year for the next 10 years, whereas the Urban Challenge fund aims to mobilise a total of Rs4tn over five years.

India’s planned funding is unlikely to resolve the structural problems with infrastructure development. The “smart cities mission” launched in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first term was similar in terms of the central government working with states and the inclusion of public-private models. It aimed to transform 100 cities into sustainable, economically vibrant, citizen-friendly urban centres. But the implementation was less than smart. A 2024 review of the project by a parliamentary standing committee made clear that its progress was unsatisfactory. Even if we set aside the usual problems of delays and budget overruns, the real failure of the mission was its inability to transform even a single city through a coherent, unified and sustainable development framework.

This is at the heart of the issue. Responsibility for infrastructure is split across the central government, states and local bodies, which do not seem to co-ordinate on plans, budgets or timelines. This is a serious problem, and the government recognises this. This year’s economic survey flagged the institutional constraints responsible for poor infrastructure, citing “fragmented metropolitan governance” and cities’ limited fiscal autonomy “to plan, finance and deliver at scale”. The problem is well understood. A solution is less clear.

How can India build world-class infrastructure? Hit reply or email me at indiabrief@ft.com

Recommended stories

Noel Tata struggles to consolidate control at one of India’s biggest groups.

Bank probe reveals Adani associates’ secret investments.

Spain is first to enter the race, as Christine Lagarde is expected to leave the ECB before the end of her term.

Mark Zuckerberg overruled 18 wellbeing experts to keep beauty filters on Instagram.

At Accenture, not using AI could cost you a promotion.

In the US, a jury will decide if bankers can be fired for demanding sleep.

Rough ride

It’s been a bumpy road for electric scooter maker Ola, with an arrest warrant against the founder and an earnings downgrade pushing the stock to all-time lows. On Wednesday, the company saw a brief uptick after clarifying that the arrest warrant issued against founder Bhavish Aggarwal by a Goa court had been set aside by the High Court of Bombay. However, the relief was short-lived, with the stock slipping back on Thursday.

The Goa case was filed by a disgruntled customer whose scooter was not repaired and returned on time. Aggarwal failed to appear for the hearings, after which a warrant was issued. While the case in isolation seems a minor issue, it is one in a long list of problems the company is facing.

Ola Electric’s service record has been consistently poor, something Aggarwal himself recently acknowledged. More significantly, its core scooter business appears increasingly fragile. Quarterly results released last Friday showed a 55 per cent drop in revenue and 60 per cent fall in volumes. Net loss, too, has widened. Most analysts have downgraded the stock. Ola Electric was listed in the markets in August 2024 at Rs76, and the stock has since lost nearly 65 per cent of its value.

Aggarwal first started Ola Cabs — the Indian version of Uber — which became one of the country’s early unicorns, before founding his electric vehicles manufacturing business in 2017. Japan’s SoftBank was an early investor in the cab business, and is also the second-largest shareholder in Ola Electric. But SoftBank too has been trimming its holdings since the company went public.

Amid these challenges, Aggarwal is attempting to pivot to lithium iron battery manufacturing. The company has set up a factory in Tamil Nadu with an ambitious target of being able to produce batteries with 100GWh capacity a year. However, last year it was pulled up by the government for missing key milestones under a production-linked incentive scheme.

So far, Ola Electric has not shown it can resolve its operational shortcomings. Instead, Aggarwal seems to be flitting from one ambitious plan to another. This is a pretty sad state of affairs for what was once one of India’s most promising start-ups.

Go figure

As international concerns mount about overcapacity in the world’s second-largest economy, the IMF has called for China to slash state support for industry. The fund estimated that China spends about 4 per cent of its GDP subsidising companies in critical sectors, and said it should reduce that by 2 percentage points in the medium term.

Read, hear, watch

I am still struggling to climb out of my funk, so instead of attempting something new, I am re-reading Siddhartha Deb’s The Beautiful and the Damned. Published in 2011 and set in the first decade of this century, Deb paints a portrait of the new India that was emerging through the stories of its people. It was a time of audacity and hope, and in reading it now, it’s clear how fragile that edifice was.

I was considering watching Wuthering Heights this weekend. But the reviews are not encouraging.

Buzzer round

Which country will vote in a referendum in June this year to cap its population at 10mn for the next 25 years?

Send your answer to indiabrief@ft.com and check Tuesday’s newsletter to see if you were the first one to get it right.

Quick answer

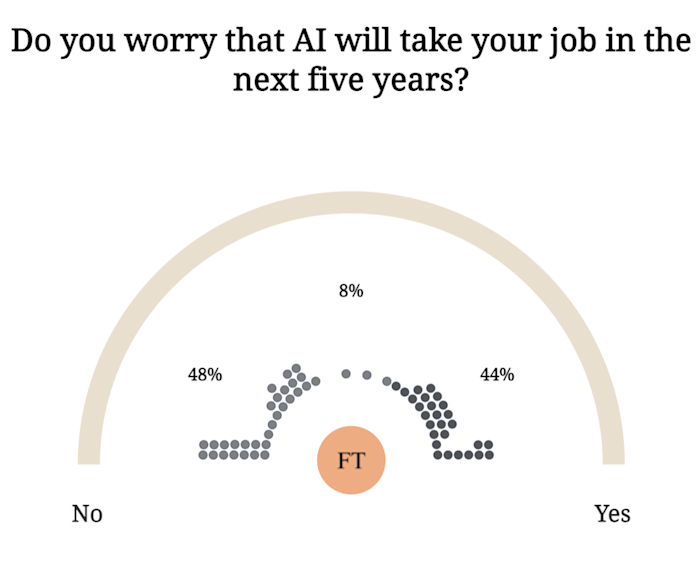

On Tuesday we asked if you were worried AI would take your job in the next five years. Here are the results — and 48 per cent of you are not. Colour me impressed.

Thank you for reading. This India Business Briefing is edited by Mure Dickie. Please send feedback, suggestions (and gossip) to indiabrief@ft.com.