For years the most typical career aspiration for a young Korean would have been to snag a job at Samsung. But a recent survey of young jobseekers showed the country has a new most sought-after employer: SK Hynix.

Lim Hee-jin, a student at the prestigious Seoul National University, calls SK Hynix “a really good company with high future potential. If a friend got hired there, I’d say ‘You got into a great place — I envy you’.”

The chipmaker is enjoying its most successful period thanks to dominance of one of the global economy’s most critical technologies — the high-bandwidth memory chips that are powering AI development.

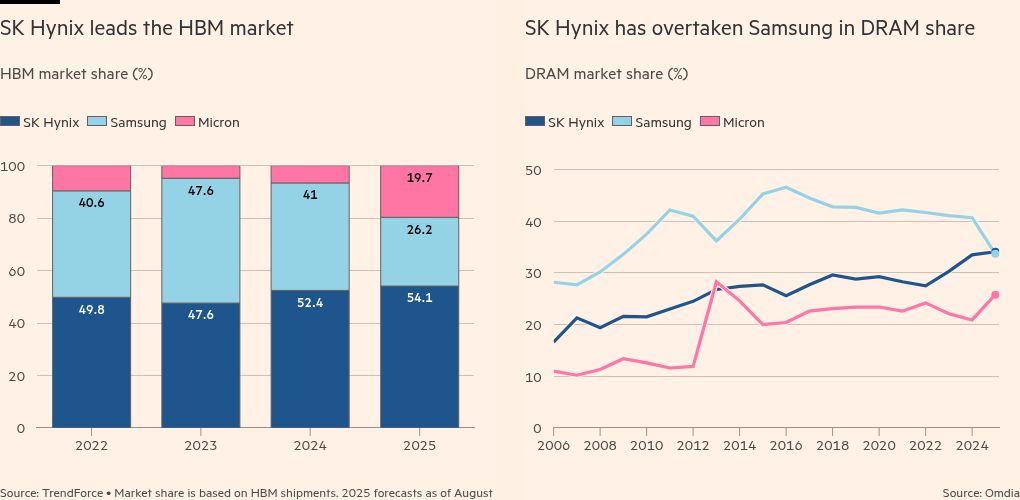

SK Hynix has outmuscled better known chipmakers, including its great rival Samsung, to claim more than half of the global market for HBM chips, which allow the massive volumes of data required for AI to flow at high speeds. The company is the primary HBM supplier to Nvidia and was recently selected by Microsoft for its own proprietary AI chips.

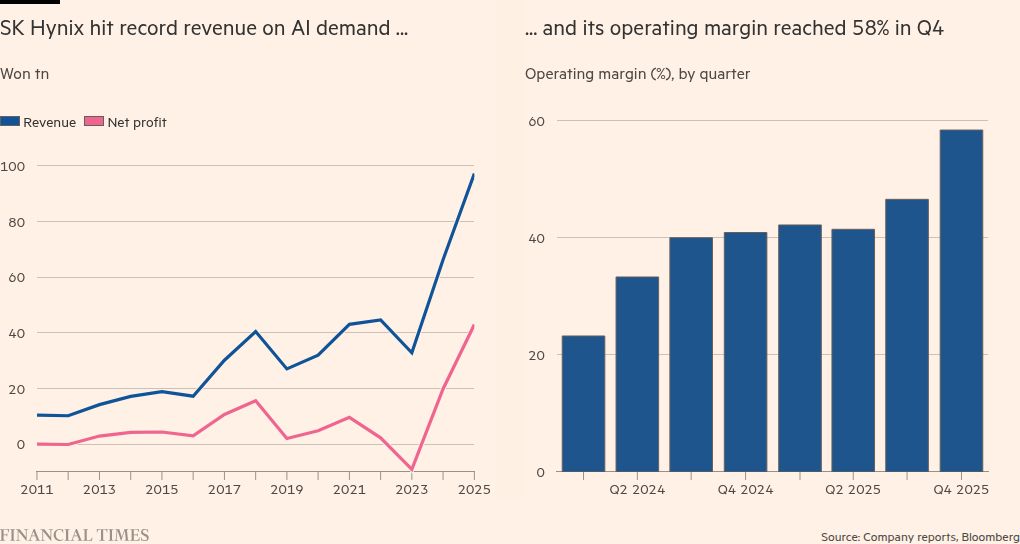

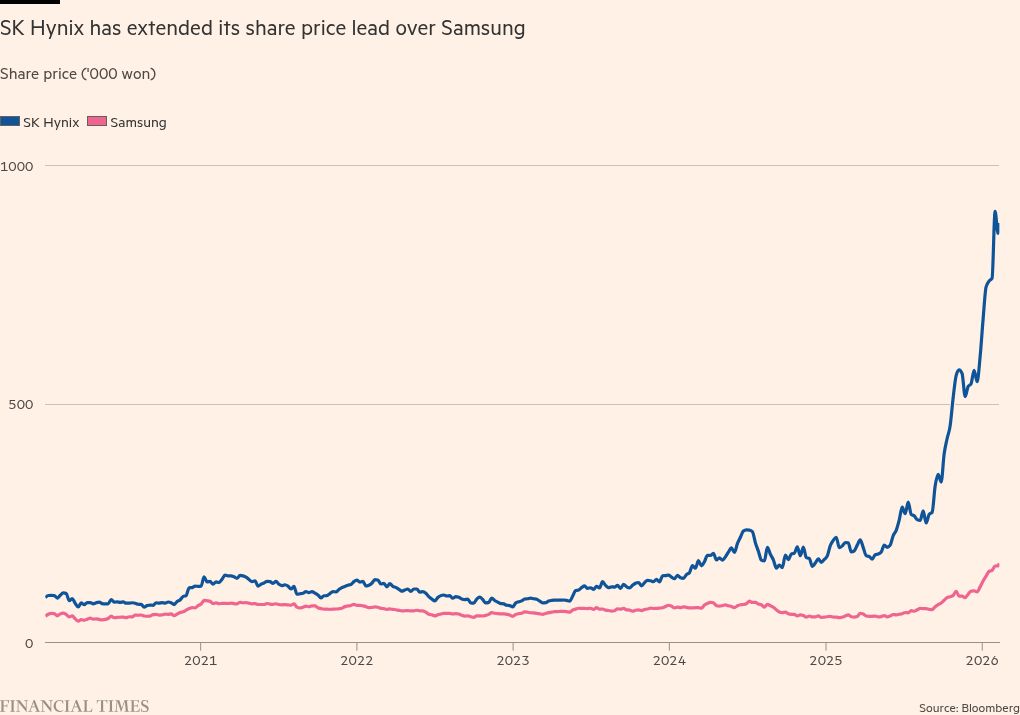

Shortages of HBM as well as less powerful Dram and NAND memory are propelling prices higher, with SK Hynix reaping the benefit. Its fourth-quarter revenues were 66 per cent higher than a year earlier while its operating margins were 58 per cent, better than even TSMC, the world’s biggest chipmaker. SK Hynix’s market capitalisation is up 340 per cent over the past 12 months to Won640tn ($438bn).

Once “a follower”, SK Hynix was “now a shaper” of the chip sector, said Professor Kwon Seok-joon of Sunkyunkwan University in Seoul. “SK Hynix has made the memory constraint its advantage.”

The company is preparing to double down on AI, moving away from just making chips by committing $10bn of capital to an “AI solutions firm”.

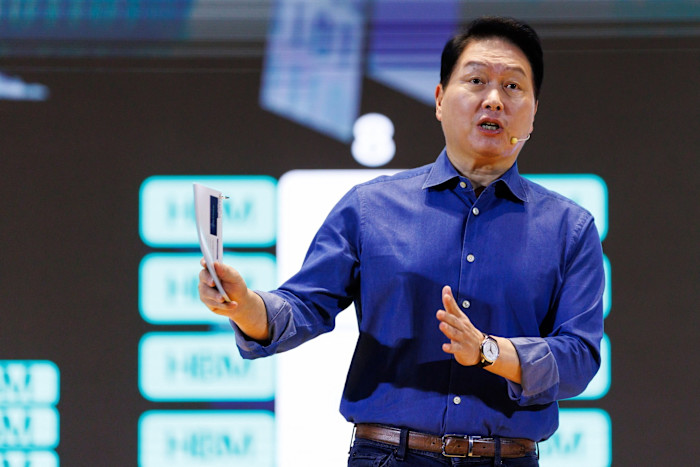

AI would be a “fourth quantum leap” for SK Group, the sprawling chaebol, or large family-owned conglomerate, to which SK Hynix belongs, group chair Chey Tae-won has said.

The chipmaker has become the jewel in the crown of SK, a former textile maker whose growth was built on the purchase of Korea Oil Corporation in 1980 and then Korea Mobile Telecommunications in 1994, which was renamed SK Telecom and became the group’s cash cow.

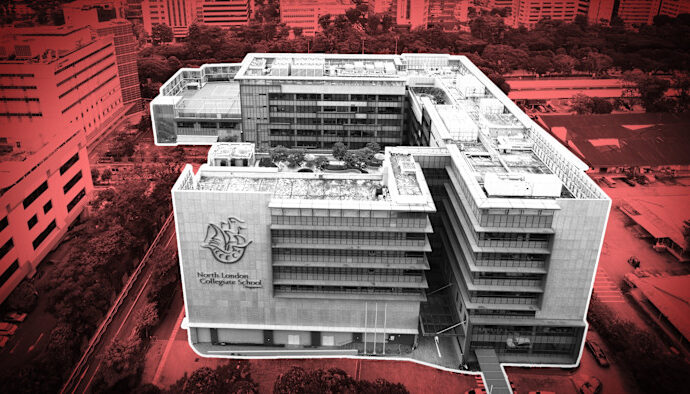

The third transformative acquisition was SK Hynix, but its current success would have seemed a fantasy throughout most of its history. Established under the auspices of the Hyundai chaebol in 1983, Hynix was a creditor-owned “zombie” firm for many years following the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis and an early 2000s Dram glut.

Suitors came and went, including Micron, which offered $3.2bn in 2002 but without agreeing to take on Hynix’s $6bn of debts. The Hynix board rejected that deal. Not until 2011 did SK Group step in when it paid Won3.4tn to end what had become known as “the Curse of Hynix”.

Many internal opponents were horrified by the idea of taking over Hynix. “There was an outcry within SK Telecom,” says Lee In-sook, director of consulting firm Platform 9¾ and co-author of Super Momentum, a book on Hynix published last month. “They said, ‘If we take over that company, we will fail. We will only pour money into it and then we will go under too’.”

Just two months after the deal went through, SK chair Chey was charged with embezzlement of group funds. He would end up serving more than two years in prison before being given a presidential pardon.

Chey however made one wise decision: the appointment of longtime Hynix engineer Park Sung-wook as chief executive. Hynix employees trusted Park and his technical background meant “you didn’t have to explain anything and you couldn’t lie to him”, Lee said in an interview.

While many employees had fled Hynix during its years of uncertainty, those who remained had developed a do-or-die, underdog mentality. At company drinking sessions, according to Lee, staff would shout “Go man go, is man is!” — a ‘Konglish’ expression essentially meaning: “If you’re going, go; if you’re staying, stay.”

Park, who stepped down as chief executive in 2019, encouraged his team to prioritise long-term research over short-term financial performance. They focused on HBM technology at a time when few others believed in it. Its first use was in a prohibitively expensive graphics card aimed at gamers. Hynix barrelled ahead anyway, increasing R&D spending an average of 14 per cent a year between 2010 and 2024.

For years, HBM seemed like a solution looking for a problem, but then came the AI boom. “AI workloads require high volumes of memory . . . it wasn’t until the launch of ChatGPT spurred an explosion in demand for AI servers that Hynix’s multiyear bet finally paid off,” says Chris Miller, author of Chip War.

According to an HSBC research note, the HBM market grew from $1bn in 2022 to $16bn in 2024, and by 2027 it should reach $87bn. Hynix revenue has increased from Won44.6tn to Won97.1tn in the past three years.

According to Prof Kwon the memory crunch is likely to continue until the fourth quarter of 2027. “Forward capacity is being locked up well in advance . . . everybody agrees memory is a chokepoint now,” he said.

While Hynix’s position in HBM production is the result of what Kwon calls “a multi-decade accumulation of knowhow”, there are plenty of potential threats including arch-rival Samsung, which was slower to the AI market for HBM but has since developed formidable capability of its own.

Ray Wang, an analyst at SemiAnalysis, said Samsung’s improvement meant SK Hynix could face a “more competitive environment” for the next generation of HBM.

Kwon believes the power of core customers such as Nvidia is a greater concern in the long run. Nvidia has a market share of 85 per cent in the graphics processing units (GPUs) that use HBM to power AI. With Hynix, Samsung and Micron vying to supply HBM, Nvidia may be able to insist on ever higher standards and customised chips, says Kwon.

Chinese competitors are also making inroads at the cheaper end of the market: Hefei-based CXMT has recently claimed a 5 per cent market share in Dram.

SK Hynix also risks becoming caught up in geopolitical tension around semiconductor supplies, including President Donald Trump’s desire for far more chips to be built within the US. The company has navigated big-power rivalry, maintaining a facility in Wuxi in China where it produces about 40 per cent of its Dram products, while recently announcing investment of $10bn in a US-based subsidiary that will focus on data centres and infrastructure for AI.

US commerce secretary Howard Lutnick this month threatened Korean chipmakers: “Everyone who wants to build memory has two choices: they can pay a 100 per cent tariff, or they can build in America.”

The market has brushed off such concerns, as has South Korean President Lee Jae-myung. “If a 100 per cent tariff were imposed, it would likely result in US semiconductor prices doubling,” he told reporters at a recent press conference.

The greatest fear of all, of an AI bust following the boom, has not quite reached SK headquarters yet. Last summer, group affiliates including Hynix broke ground on Korea’s largest AI data centre, a Won7tn project in the coastal city of Ulsan. SK Hynix would “build the most efficient AI infrastructure by providing everything from semiconductors to power and energy solutions”, Chey said at a company event last year.

Interviewed in Lee’s book, Chey said the past decade had been a journey “to make Hynix capable of fighting on the battlefield”.

“The next 10 years will be about changing the battlefield itself,” he said. “I want to use the AI boom as a trigger to propel SK Hynix on to the global centre stage.”