Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

If you want to take a gloomy view of the prospects for trade and globalisation based on the year so far, you’re not short of material. Donald Trump has threatened tariffs against the EU for resisting his desire to annex Greenland, and against anyone trading with Iran or selling oil to Cuba. A brutally frank speech by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney has articulated widespread fears about the fragmentation of the global order.

But it’s difficult to point to hard evidence, even after a full year of Trump in office, that these stresses are causing serious damage to trade in goods and services. His tariff campaign is so badly run and has hit so much resistance it may already have peaked, and the system has proved itself flexible enough to adapt. Longer-term trends towards politicising and weaponising globalisation of course remain in place, but for now the most striking thing about world trade is its resilience.

US imports in value terms surged early in 2025 to get ahead of Trump’s tariffs but have since returned to normal. Despite a downward blip in imports in October, reversed in November, the US shows few signs of ceasing to be a source of global demand.

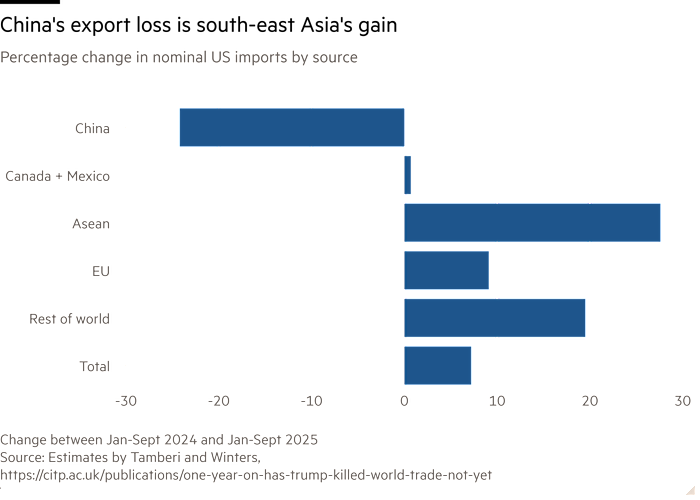

Patterns during Trump’s first term are being repeated. Bilateral tariffs against China have certainly squeezed goods trade between the two economies, with Chinese imports falling by 24 per cent in the year to September 2025. But those from south-east Asia and to a lesser extent Europe have increased, while those from Canada and Mexico have held up surprisingly well.

Trump declared that he would stop China repeating its earlier trick of end-running US tariffs by routing exports through third countries, and promised to block what he calls “transshipment” with 40 per cent tariffs. It doesn’t seem to have worked yet, or certainly not to the point of restricting trade rather than diverting it. Meanwhile, services trade is outpacing goods, the political tensions over US tech not yet having had a material effect.

It’s perfectly plausible that the US has hit peak tariff. Twice now Trump has threatened confrontation with another trading superpower, China in October last year over the trade deficit and the EU in January over Greenland. Both times, faced with the threat of retaliation and financial markets reacting badly, he backed down.

This week, following last week’s EU announcement of a trade deal with India, Trump rapidly promised to reverse some of the massive tariff increases he had imposed on Indian imports last year. India generally welcomed the announcement but did not comment on Trump’s claim it had agreed to buy a ludicrous $500bn of US exports nor stop buying Russian oil as a quid pro quo. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, massively more popular with his voters than Trump is with his, knows the US president would benefit from an agreement more than he does.

That EU-India trade deal may not quite have lived up to its game-changing geopolitical billing, but it certainly underlines that most of the rest of the world is not following the US down the primrose path to wholesale protectionism. Across the world’s emerging economies in Latin America, Africa, south and south-east Asia there are plenty of strains to be managed, especially with Chinese imports, but it is emphatically not a trading environment gripped by a sense of crisis.

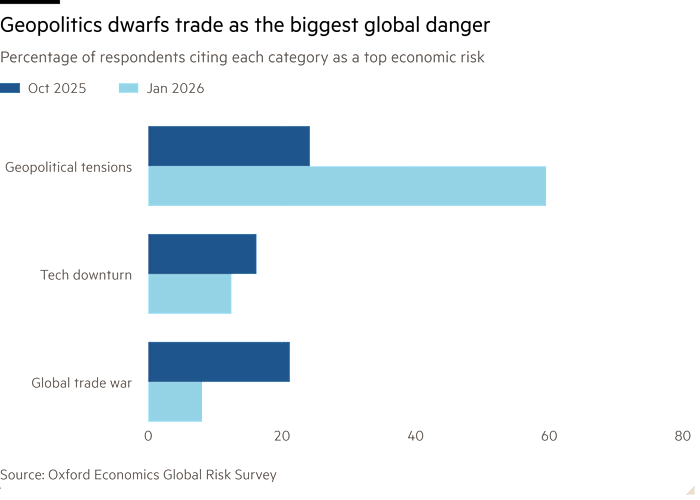

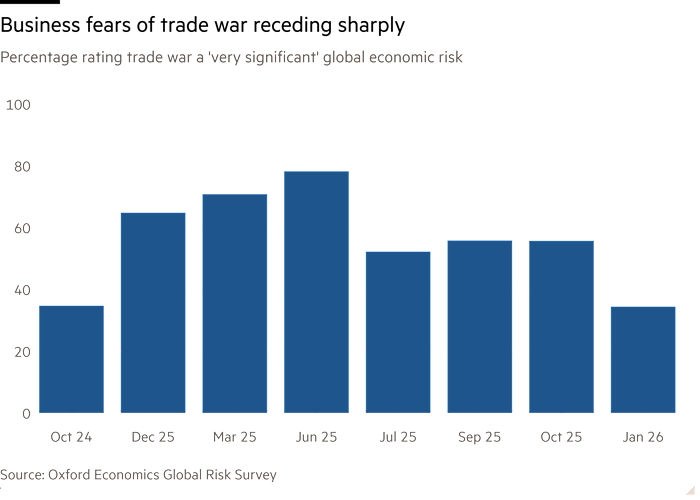

Businesses are also relaxing their fearful crouch. Polling of a panel of businesses by the consultancy Oxford Economics shows that fears of a global trade war over the next two years are back to the levels seen before Trump’s election and less than half their peak of last June. Respondents now rate geopolitics — in the hard sense of outright war or heavy sanctions — in places like Ukraine, Taiwan, the Middle East and Venezuela as a far bigger threat to the global economy than a trade war.

Some of those shocks, particularly China invading or blockading Taiwan, will have massive implications for trade. But companies’ perception of the threat from protectionism itself in the form of tariffs, quotas, local content requirements and so on has sharply receded.

Making predictions is obviously a big hostage to fortune, but trade — particularly in goods — has so far vindicated those of us who habitually point out its remarkable powers of self-correction to economic and political shocks. Of course the longer-term risks remain, and perhaps have intensified, notably the use of mineral export controls, battles for technological supremacy and the politicisation of payments systems.

But the tentative conclusion from a year of Trump is that his antics with tariffs are another shock the global trading system is weathering without catastrophe. The US president is strong, but market forces are stronger.