This happened quite some time ago, but very late one night, I lent a hand to a young woman who had fallen down the stairway of a pedestrian overpass. This happened in Tokyo, where a major road abuts a residential area. It was dark; there was no one around. She had tumbled down and hit almost every step; she was still conscious but was unable to speak. She was spectacularly drunk, and was crying the whole time. It didn’t seem like she required medical attention, so I had her drink some water and saw her all the way home in a cab. The next day, she must’ve found the note I’d left her with my number, since she gave me a call. “Thank you so much!” she said. “I’m going out again tonight, but I’ll be careful not to get as drunk as last night!” Part of me couldn’t believe this was her takeaway, but at least she was upbeat.

There are, of course, a few distinct varieties of drinking. First, there’s drinking voluntarily, for fun. Then there’s the kind of drinking that isn’t really fun, but feels like the only way to make life tolerable, in what amounts to escapism or self-harm. The third variety is when you drink, or get other people to drink, as a way of making money. If I’m going to write about nightlife in Tokyo, this third one is impossible to ignore.

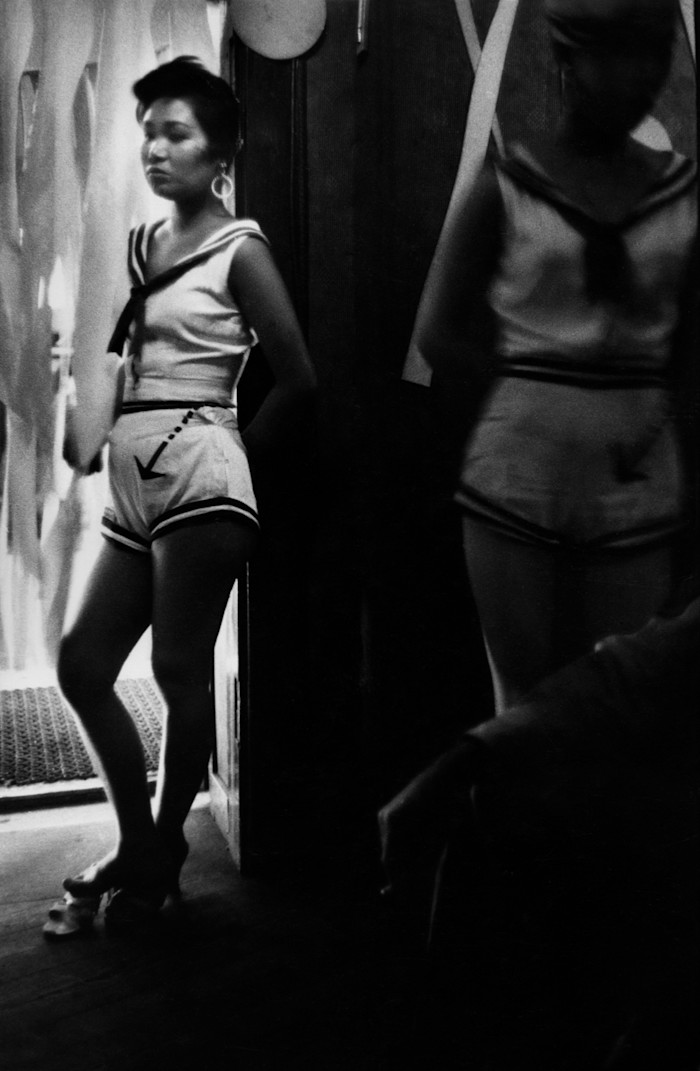

In Japan, there’s a whole universe of places you can have a drink, from izakaya or pubs, to standing bars, micro-bars, girl bars, sunakku or small bars, lounges, kyabakura or hostess clubs, supper clubs, host clubs where men serve women, and luxe members-only clubs. Each has its own specific culture, rules and pricing system. For readers outside Japan, I get the sense that the establishments where women drink with guests are a bit hard to understand.

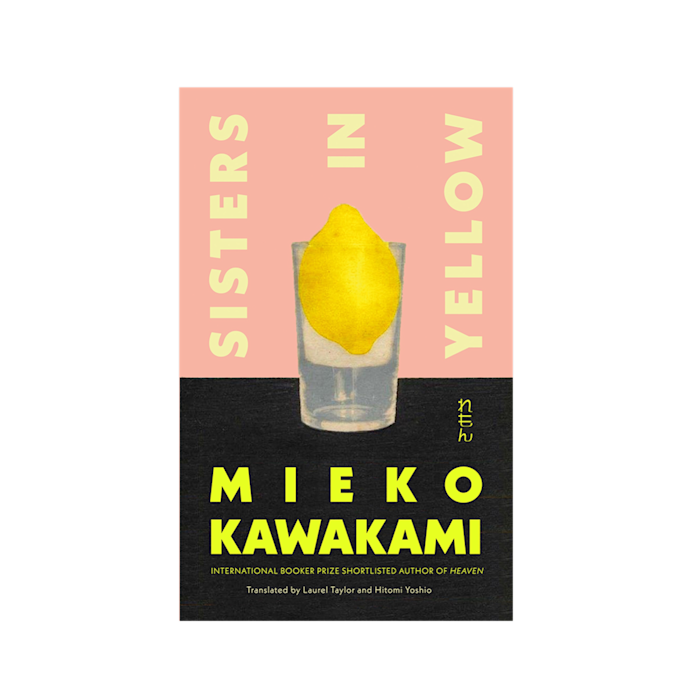

As it happens, my novel Sisters In Yellow features a sunakku called Lemon. You could think of sunakku (which comes from the word “snack”) as a neighbourhood drinking spot run by a group of women, which is the case in my novel. The prices are reasonable. It’s part of the community. On the other end of things, you have the members-only clubs, which charge close to ¥100,000 (about £470) just for a seat. In Tokyo, you’ll find clubs like these clustered in Ginza, while in Osaka, it’s Kitashinchi. Their customers are social elites such as politicians, business owners, celebrities and athletes, and the hostesses, who get their hair done every day, greet guests dressed in immaculate kimonos or dresses, consummately trained. You need to have an in to show up at these clubs; you can’t simply drop by.

When I was younger, I worked at one of these high-class establishments. I was raised by a single mother in a house saddled with debt and my kid brother’s college tuition. But I managed to pay for everything, clearing the books, by working at a club that paid good wages. Granted, my other experiences of work at factories, chain restaurants and bookstores, along with washing dishes and studying philosophy through a college correspondence course, all taught me things I couldn’t have learned any other way. But the night world shows you things that never see the light of day. The women of that world looked after me and offered strict instruction, showing me the ropes as they taught me the ways of the world, including its lack of fairness. I’m not making a joke when I tell journalists that “I graduated from Hostess University”. I get the sense that all that matters about being in – or moving through – society came to me via the people and the ways of this world of the night.

That said, it was a confusing time for me. Friends my age were sheltered by their parents, giving them ample space to think about themselves. From where I stood, it looked like they were basking in their youth. These friends were at a loss to comprehend my situation too. I was living my life, doing my best to thrive, though I felt vaguely ashamed about not having someone to look after me financially. This was more than 30 years ago, and being a hostess was a struggle – even if some women managed to save up enough to open their own clubs, almost everybody came into the profession with some kind of a dilemma.

But times change, and Tokyo’s nightlife as I knew it went through major transformations with the arrival of social media. As these kyabakura and lounges, with their unique pricing systems, reached new heights of prosperity, the women who worked there became a new kind of modern role model, capturing attention with their vital energy. Dressed head to toe in designer clothes, they eat expensive foods, treat cosmetic surgery like just another part of skincare. Regulars compete to see who can spend the most on their favourite hostesses, the top tier of whom can make hundreds of millions of yen per year. But once people caught wind of this kind of thing, they mistook it for the norm.

To girls out in the country, not a penny to their names, the idea of the self-made woman was a source of gleaming hope. Coming from poor families, they might work their tails off at a conventional job and still struggle to clear ¥2.5mn a year, even with a college degree. But here was a different kind of job, one they could only do while they were young, an opportunity to create new connections and save money, turning their life around.

Another place where money and drink cross paths is the host club. The men spending money on the kyabakura girls are the rich guys who’ve succeeded in the world. But at the host clubs, where it’s men doting on women, the customers shelling out small fortunes are mostly lower-class women, many of them sex workers.

The people who partake in, sustain and endure Tokyo’s nightlife represent a vast array – which I’m not pretending to have covered here. Let’s just say that much of the time, your body is the commodity.

To see this at its extreme, just look at the side streets by the Shinjuku Toho Building in Kabukicho, where neglected kids from all over the country, with no place left to go, sit on the ground, asleep or drinking every hour of the day, not even a roof over their heads. Several of them, after overdosing, have even fallen down and died. Sex work happens right out in the open. It’s harrowing to see the ugly side of the desire that comes out at night, along with the sheer power of money. This changes little from one era to the next.

Readers outside of Japan, perhaps, imagine Tokyo nightlife as a scene unfolding on the top floor of a skyscraper, where you might look back from the twinkling city lights just as another perfect dish is placed before you with uncompromising service at a reasonable price. Or perhaps there’s a sense of Tokyo as a place of strangely sophisticated tastes in culture. But underneath it all, down at ground level, you’ll find people who keep tumbling down the stairs, every inch of them bruised and beaten.

Sisters In Yellow takes place in 1990s Tokyo. This was the decade of the Kobe earthquake and the Tokyo subway sarin gas attacks carried out by the Aum Shinrikyo cult. Set at the beginning of what’s now called the Lost 30 Years, it follows the protagonist, Hana, as she survives her teens and comes of age. Thanks to her innate cheerfulness and perseverance, she takes every situation as a chance to tap into what it means to be alive. I wanted to portray the humming energy of someone who is unable to turn away from living, following Hana as far as she would go.

In life, you can only see the path after you’ve taken it, leaving it up to you to decide whether it was actually worthwhile. Maybe we’re all falling in the same way, with the major difference being whether we see ourselves as having “fallen” or “landed” when we get wherever we wind up. It’s all too easy to cast judgment and point fingers at others, gossiping about how hard that guy failed, or how so-and-so really made it far. All we can really say for sure is that what we see on the outside rarely matches what’s going on internally.

Regardless of the way it looks to others, if you feel like you’ve made a landing, that’s enough. No matter how bruised up or worn out you may be: if you can make it to a point where you can tell yourself, I made it, then you’ve made it. That’s a landing, that’s enough. Which isn’t to say that falling is bad, or that landing is some grand achievement, which it’s not. I suppose the thing not every fall can guarantee, but that most landings do, is that you’re still alive.

Now and then, I think about that woman’s voice, the way she sounded when she called me the morning after she fell, clanging down the metal staircase of the overpass, crying all the way. Life isn’t fair. We need money to live, and almost everything we do is painful. I just want the people working through the night, especially the young ones, to keep living.

Sisters In Yellow by Mieko Kawakami is published on 19 March by Picador