Even if they don’t know his name, most of Singapore’s 6mn inhabitants have reason to be grateful to Liu Thai Ker.

In the eyes of many Liu, who died this month aged 87, was the “architect of modern Singapore”, the man who designed the state-subsidised housing that has underpinned the growth of the former British colony in its six decades of independence.

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong praised Liu as the “father of urban planning” in the city-state, while President Tharman Shanmugaratnam said he “helped make Singapore a liveable city in the tropics”.

Despite the city-state’s credentials as a free-market entrepot, more than three-quarters of its citizen and permanent resident population live in 1.1mn government-built flats, bought at subsidised rates.

Clusters of the sturdy towers, which typically boast leisure facilities, cheap food vendors and grocery stores, dominate Singapore’s inland skyline and have become a defining part of its national character.

“Singapore’s public housing is its national bedrock — it’s a fundamental part of national progress,” said Christopher Gee, deputy director of the Institute for Policy Studies at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Yet while Liu’s death this month was greeted with plaudits for his work, it also raised questions about whether the model is still fit for purpose.

Rising property costs, notably in the resale market, have sparked concern over affordability, while the lottery system for allocating flats, which favours traditional nuclear families, is being tested by changing social norms. Over the longer term, property values are also being eaten away by the 99-year leases on which they are sold.

“The main thing that worries me is that . . . as the lease clock ticks down and as the stock ages, housing equity drops to zero,” Gee added.

Singapore’s public housing system is now facing problems that were not considered when it was kick-started six decades ago with the launch of the Housing and Development Board (HDB), whose initials are typically used as a shorthand for the apartments. The idea was to provide good-quality, subsidised housing for people making their first step on to the property ladder.

“It looks as if this was a system that was very well thought out from the beginning — but this is not the result of a grand vision,” said Chua Beng Huat, emeritus professor at Singapore Management University School of Social Sciences.

The Malaysia-born Liu was then chief architect at the HDB, where he oversaw the development of half a million homes and 20 new towns. He also served as chief executive and chief planner at Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority, which oversees Singapore’s urban development.

Liu was acutely aware that many of the HDB’s first residents were leaving overcrowded slums or villages known as kampongs. He added communal spaces and wide corridors to his designs to create what came to be known as “vertical kampongs”.

He was also wary of creating a drab, utilitarian skyline. Many of the developments were painted in pastel colours to reflect traditional Malay culture. “To me, every HDB block is as beautiful as Miss Universe,” he said.

When Singapore introduced national service after gaining independence in 1965, home ownership was also encouraged as an incentive for conscripts to fight for their country. Today, more than 90 per cent of Singaporeans live in an owner-occupied home — among the highest rates in the world.

Properties are allocated to would-be buyers via a lottery system to applicants who are typically required to be married, engaged or older than 35.

Prices are eased through a raft of government subsidies based on personal circumstances. Singaporeans can also dip into their mandated savings and pension plans and obtain mortgages and loans from the HDB directly.

But critics have said that the lottery system is unfair to singles and non-traditional families, for whom it is harder to get a flat. Singapore’s marriage rate has been steadily falling in recent decades, dropping from 57 per 1,000 unmarried males in 1994 to 42 in 2024.

The HDB system has also been used by Singapore’s government to promote multicultural integration by setting limits on the proportion of different ethnic groups in the same estate. However, this policy has caused problems for some in the resale market by restricting potential buyers.

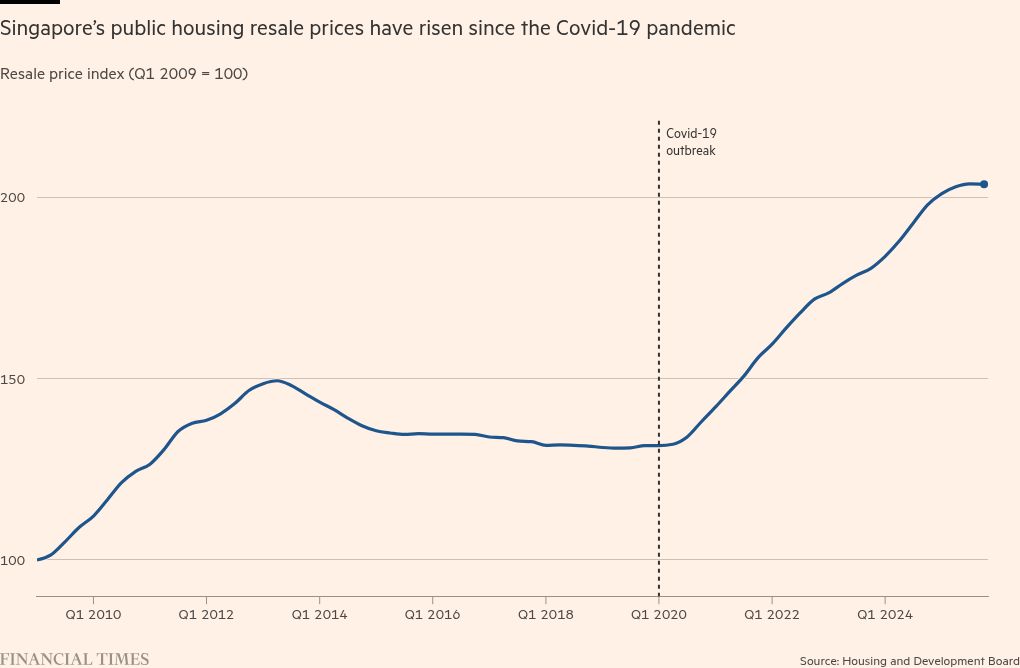

The system has also come under recent strain. Construction ground to a halt during the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting in delays to new HDBs coming on to the market. Wait times to move into a property rose from three years to as many as six.

As a result, more buyers turned to the resale market, where HDB owners can sell properties after five years of occupancy. This led to a sharp rise in resale prices, especially in more desirable estates.

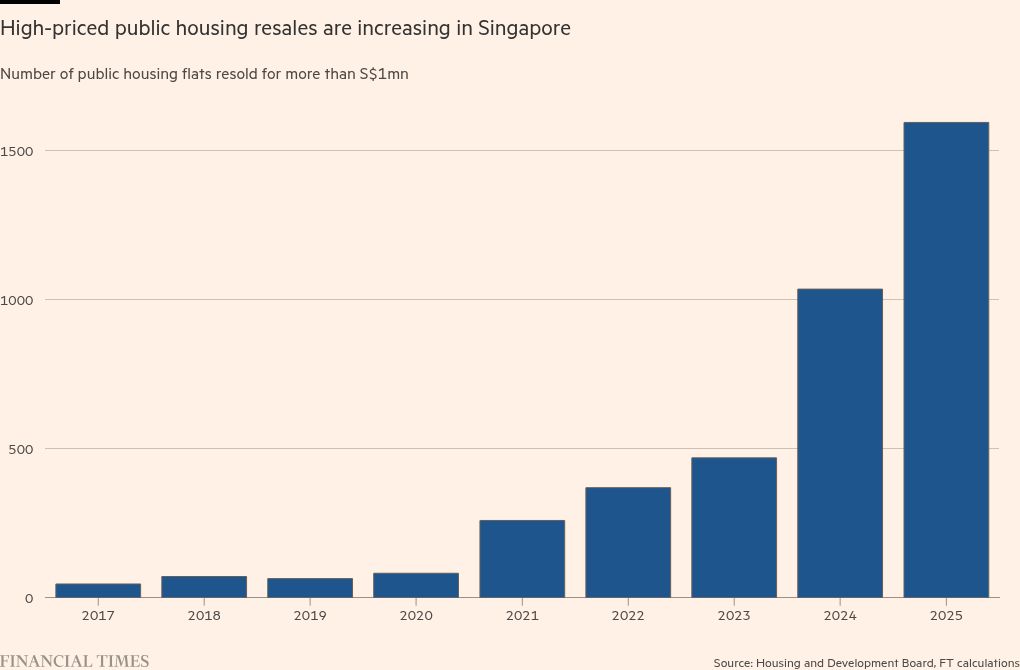

The number of HDB flats that sold on the secondary market for more than S$1mn (US$789,000) has steadily climbed in recent years, from 82 in 2020 to 1,035 in 2024 and 1,594 last year, according to FT analysis of official data.

Rising prices have become a charged political issue in Singapore, where cost of living concerns dominated last year’s general election. The government has pledged to build more than 50,000 new flats between 2025 and 2027, many with waiting times of less than three years. It has also offered more subsidies to lower- and middle-income buyers.

HDBs are still considerably more affordable than private-sector housing. The average HDB was 4.3 times the median worker’s salary in 2024 — one of the lowest rates in major Asian cities, according to the Urban Living Institute. By comparison, the cost of the average private home was 16.9 times higher.

But as Singaporeans deploy savings to fund HDB purchases and resale values rise, the properties have increasingly come to be viewed as an investment asset and a retirement nest egg.

“The asset accumulation idea is very much entrenched,” said Gee. “The system has concentrated people’s personal balance sheets in their housing equity and fosters this notion that property is a pathway towards increased wealth.”

One threat to that model is the 99-year lease terms, after which properties are to be returned to the government. As the oldest HDB units enter their final three decades, that approaching deadline is eroding their value.

“What will happen at that point?” said Chua. “That is a big political issue.”

Liu himself had warned that leaseholders “must respect that at the end of 99 years, the flat goes back to the government”.

He also expressed concern in a 2022 interview that “public housing has become a kind of business venture, rather than actually solving the housing needs”.

“I feel that the implication may not be very good for the economic development of Singapore,” he said.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong