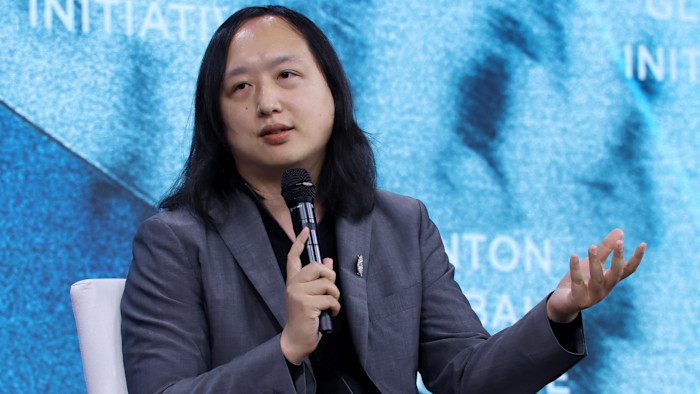

According to Taiwan’s roving cyber ambassador Audrey Tang, social media resembles fire. When contained, it is like a campfire that fosters community and keeps campers warm. Left unchecked, it rages like wildfire, devastating people’s lives. How best to control it?

Around the world, politicians are struggling with how to tame the flames of online extremism, disinformation and deepfakes, now increasingly fuelled by AI.

This week, the EU launched a formal investigation into Elon Musk’s xAI following public disgust at the circulation of deepfake sexualised images. If xAI is found in breach of the EU’s Digital Services Act, the company faces fines of up to 6 per cent of global turnover.

In the US, a Los Angeles court is hearing a landmark case against Instagram and YouTube over whether their services are addictive and harmful for children. The two social media platforms are vigorously contesting the claims — even if Snapchat and TikTok have already settled for undisclosed sums.

These actions reflect Europe’s instinct for regulation and the US preference for litigation. But both expose the fundamental divide between technology companies, which treat people as consumers with narrow interests, and governments, which view them as citizens with broader rights.

Other approaches, though, may offer better ways to bridge that divide. One of the most interesting is Taiwan’s experiment with deliberative democracy, which has generated fast and flexible policy responses to many issues, including social media.

As a student activist who later became Taiwan’s minister for digital affairs, Tang has been central to this deliberative democracy initiative. She points to the island’s success in tackling deepfakes and disinformation by inviting 447 citizens to discuss appropriate responses.

These 45 citizens’ assemblies suggested community notes should be attached to suspicious posts, that social media companies should share liability for deepfake scams and that their services should be progressively “throttled” until they complied with such requests.

As a result of collective efforts, Taiwan’s Ministry of Digital Affairs reported a 96 per cent fall in online scam ads last year and a 94 per cent reduction in identity impersonation.

Asking voters “What sucks?” and adopting their collective solutions has made democracy “fast, fair and fun” and boosted the government’s popularity, Tang tells me. Many other countries, including Ireland, Japan, Germany and the UK have also been exploring deliberative democracy as a way to address knotty problems.

Tang argues that the old “Newtonian” style of democratic politics, which revolves around formal political institutions and set election cycles, is no longer suited to a world of rapid change and mutating online identities.

Nowadays, voters inhabit a “quantum” world, where they live in superposition as both consumers and citizens and can randomly interact with anyone online. “Each aspect of us behaves differently when we are entangled with a different community,” she tells me. “People are only polarised if you measure them in Newtonian terms.”

The theory of quantum politics has also been explored by Armen Sarkissian, the former president of Armenia and theoretical physicist, who has just finished a book on the subject. In his view, political institutions must better adapt to quantum-like phenomena, such as pandemics, terrorist acts and social media-instigated eruptions.

Citizens’ assemblies may well be part of the answer. But their effectiveness still depends on their ideas being scrutinised and enacted by representative institutions, says Jack Stilgoe, a policy professor at University College London. Otherwise they are little more than elaborate focus groups. “Deliberative democracy only works when it is part of a thriving democratic sphere,” he says.

To their credit, some tech companies are themselves trying to harness the wisdom of crowds to improve their design choices. But these initiatives are unlikely to work in isolation because they lack democratic legitimacy.

And, as both consumers and citizens, we all have a responsibility to ensure that campfires do not spark wildfires. As The Washington Post has reported, even an apolitical subreddit group with 844,000 followers sharing videos of cats being played like bongos (yes, really) has now been taken over by anti-ICE protesters. But in their own way, the cat drummers have moderated a lively, and mostly respectful, debate. That rather proves Tang’s point that citizens have multiple identities, not one fixed worldview.