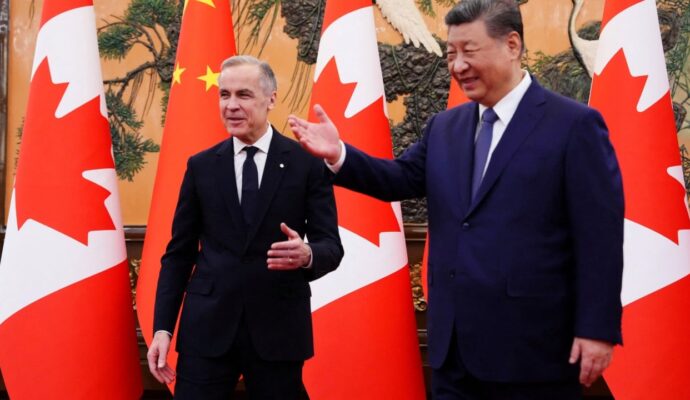

In an age defined by intensifying competition between the United States and China, governments increasingly feel inclined to show where they “stand”. Yet the Greenland episode should prompt a deeper reflection – not only in Denmark, but across Europe and the wider Western world – about the risks of narrowing diplomatic space too hastily.

Advertisement

Confucius Institutes, whatever criticisms one may hold about their governance or oversight, were jointly established by Chinese universities and host universities. Their primary function was to teach the Chinese language, enable cultural exchange and provide institutional channels for engagement. In diplomatic terms, they functioned as bridges: imperfect, contested, but nevertheless useful.

By dismantling these bridges entirely, Denmark did not merely reject a cultural programme; it signalled a broader unwillingness to tolerate even low-risk engagement with Chinese language and culture. That choice went far beyond managing risk. It amounted to closing doors.

Advertisement

The decision appeared largely cost-free. Denmark enjoyed strong transatlantic ties, a relatively stable European environment and little perceived need to hedge. China, after all, was portrayed as a distant challenge best managed through collective firmness rather than selective engagement. But the strategic environment has shifted.