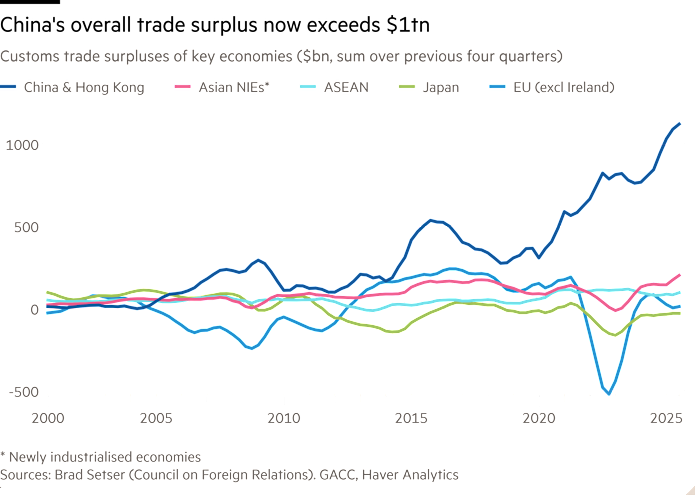

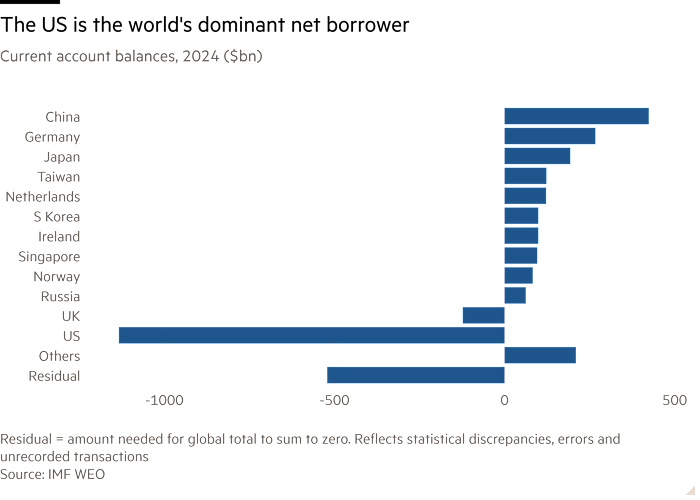

In the first 11 months of 2025, China ran a customs trade surplus of over $1tn. According to Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations, in 2025 as a whole, its “overall goods surplus . . . should — if accurately measured — approach an astonishing $1.2tn dollars (6 per cent of China’s GDP, well over a percentage point of the GDP of all of China’s trading partners).”

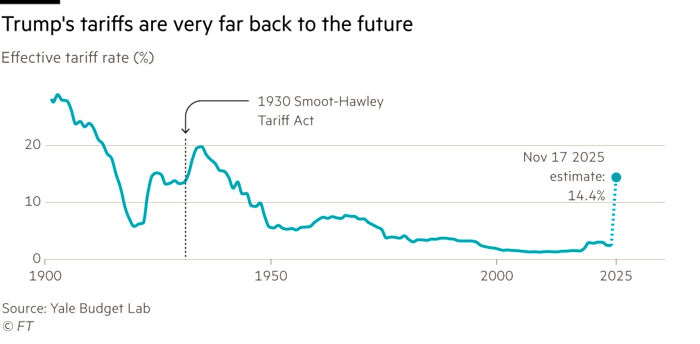

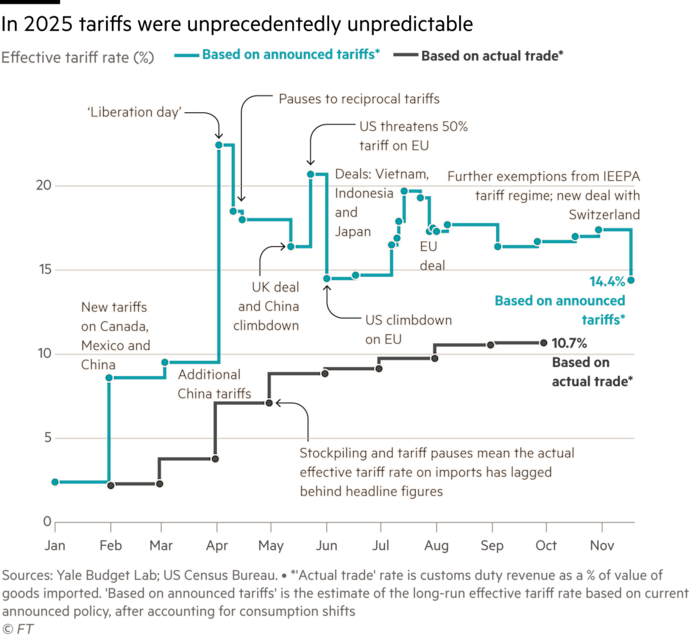

Over much the same period, Donald Trump, obsessed with US trade deficits — both overall and, even more, in manufactured goods — raised average tariff rates to an estimated 14.4 per cent, the highest level since shortly after the second world war.

Why is China running such huge trade surpluses and why is the US abandoning the relatively liberal trade policies of the past eight decades? The answer is the revival of mercantilism.

Mercantilism dominated European thinking on international economic policy in the 17th and 18th centuries. Mercantilists’ underlying belief was that international economic policy is primarily a tool of state power. Since power, unlike prosperity, is relative, mercantilists think of international economic engagement as “zero sum”: you win, I lose. Mercantilists also treasure domestic production and love trade surpluses and protection against imports. Adam Smith, wrote The Wealth of Nations in the 18th century as an argument in favour of free trade, against just such mercantilism.

Mercantilism goes back at least to the 16th century. So, given that we are in the 21st, we should call today’s version “neo-mercantilism”, replacing “neoliberalism” which took a more Smithian view of trade a few decades ago. Yet as the Canadian economist, Eric Helleiner argues, such contemporary neo-mercantilism partly revives earlier neo-mercantilist ideas, notably those of two figures whose ideas were influential in the 19th century — the first US secretary of the treasury Alexander Hamilton and the German political theorist Friedrich List, both of whom argued for infant industry protection.

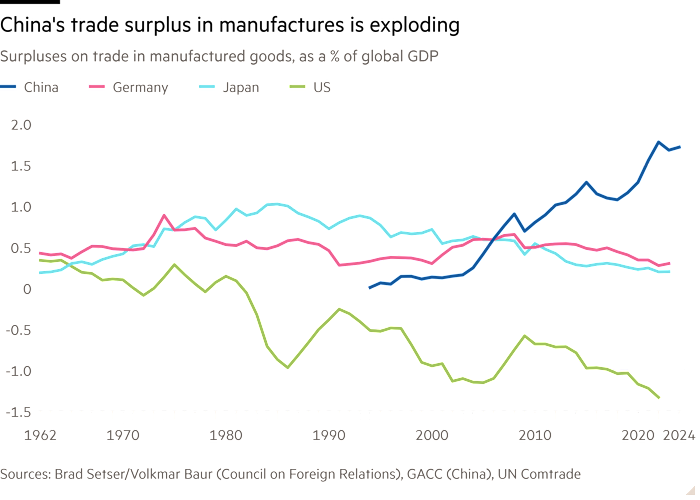

Neo-mercantilism is thriving in China, which has not only embraced infant-industry promotion, but created huge trade surpluses. Trump’s US is no less neo-mercantilist: he is obsessed with the evils of external deficits and the need to protect domestic markets.

Arvind Subramanian, former chief economic adviser to India’s prime minister Narendra Modi, recently argued that “Trump’s long-standing tariff obsession derives from his fury-fuelled conviction that trade surpluses abroad have damaged the US economy, especially its manufacturing sector. In that world view, China, with its consistently large trade surpluses, was the provocateur-in-chief.”

My colleague, Robin Harding, has raised even more disturbing worries about China: the Chinese, he suggests, do not want to import anything manufactured elsewhere. Their aim, he argues, is domination of global manufacturing.

This perspective is consistent with the revealed preferences of Chinese policymakers over decades. Certainly, China has never addressed its long-standing structural problem of excess savings. True, immediately after the financial crisis of 2007-09, its temporary “solution” was to promote a huge domestic property boom. But this has now (inevitably) blown up. More recently, the favoured solution has been enormous investment in advanced manufacturing, which generates excess capacity and even higher exports: China’s mercantilism is embedded, economically and politically.

Trump’s tariffs will now divert China’s exports towards other markets, both other high-income economies and emerging and developing ones. Thus, Subramanian notes that “China’s exports of low-value-added goods to developing countries have been rising sharply, undermining the competitiveness of these countries’ own domestic industries.” The beggar-our-neighbours interaction of China’s mercantilism with US protectionism will spread damage across the world.

Mercantilism’s zero-sum and state-oriented perspective also tends to create international conflict. Mercantilist powers fought one another constantly: England and France, two of Europe’s great powers, were at war, on and off, from 1689 to 1815. The apparently economically-motivated US decapitation of Venezuela is a classically imperialist resource-grab. Maybe, the fear of nuclear weapons will continue to constrain war. But it is not easy to separate intense economic friction from outright conflict.

The triumph of neo-mercantilism then raises two fundamental issues.

More stories from this report

The first is where it will lead. Some argue that the world will fracture. This seems likely. But it is unlikely to be a neat fracturing, because the interests of great powers overlap. It seems unlikely, for example, that the US will just abandon south and east Asia to China.

Again, in the mercantilist era, there was agreement that gold was a politically neutral form of money. Today, the world’s money (like it or not) consists of national fiat currencies, predominantly the dollar. Replacing it would be very messy. Above all, today’s world economy is more integrated, on almost all dimensions, than any that existed in previous eras. The costs of fracturing are likely to be correspondingly high, especially for small and vulnerable countries.

The second question is whether the fracturing can be managed. There is, in fact, an answer that is rational, albeit optimistic. It is to build a new system around the notion of a peace treaty among mercantilists. Surprisingly, perhaps, that would not be a new idea: just such a peace treaty was an important element in the post-second-world-war liberal settlement that China and Trump’s US are jointly destroying.

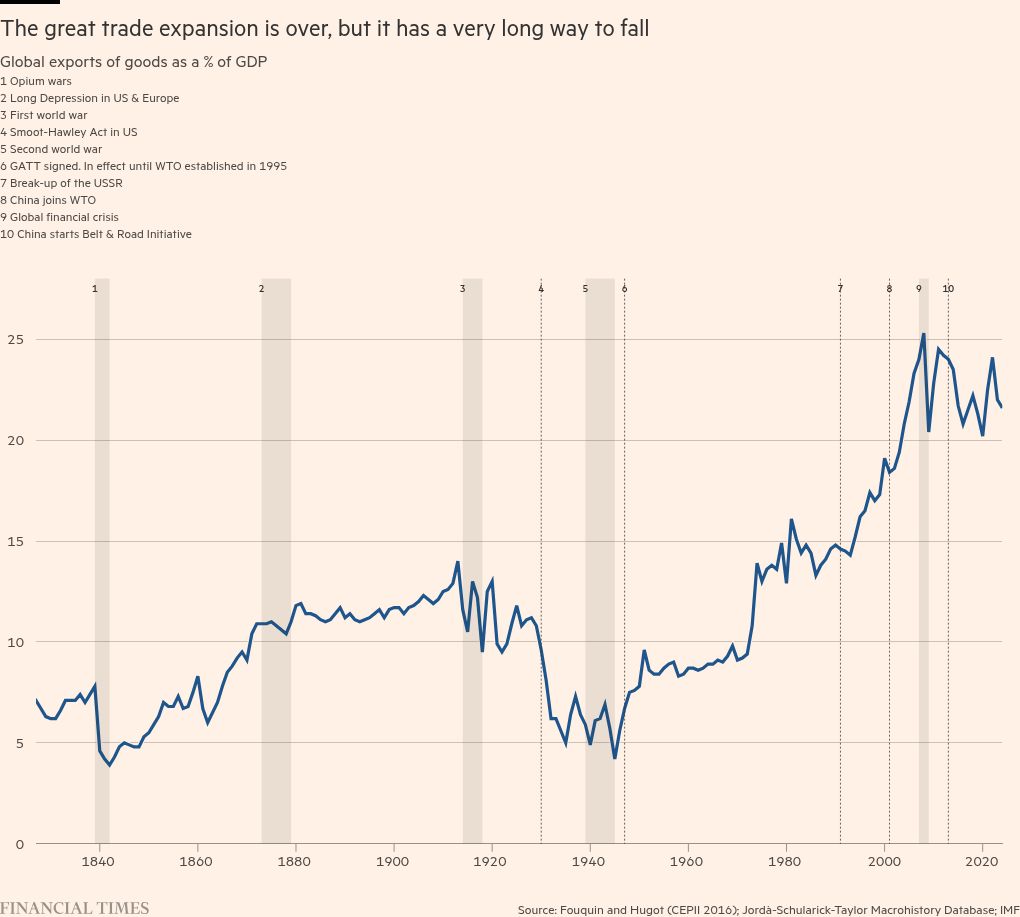

Thus, the underlying principle of trade negotiations in 1947’s General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs was reciprocal liberalisation: you lower your barriers to my exporters and, in return, I will lower mine to yours. This is far from the economists’ case for unilateral liberalisation. But it worked rather well, especially in combination with the more liberal principles of non-discrimination and national treatment.

Thus, one could imagine an effort (albeit not under Trump) to design a new multilateral economic treaty. In the process, one could even include something John Maynard Keynes wanted to achieve at Bretton Woods, namely, a way to combat huge structural trade surpluses. These, he believed, imposed ruinous constraints upon others. In the 1940s he could not persuade the US, then a huge surplus country. Today, not only the US, but perhaps the Chinese, too, might see that its mercantilism creates serious macroeconomic and microeconomic difficulties.

Neo-mercantilism is a reality. But it needs to be managed. Policymakers need to respond imaginatively.