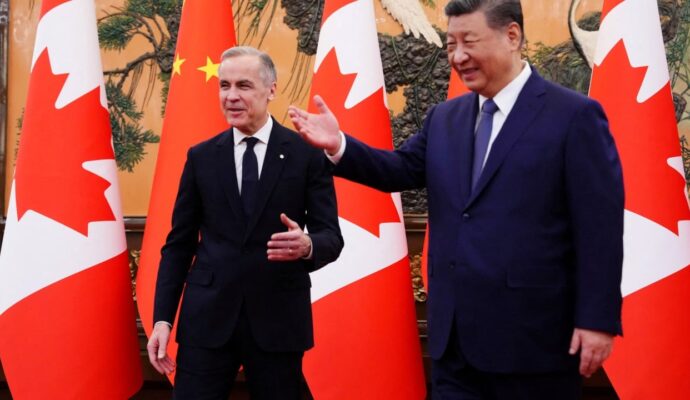

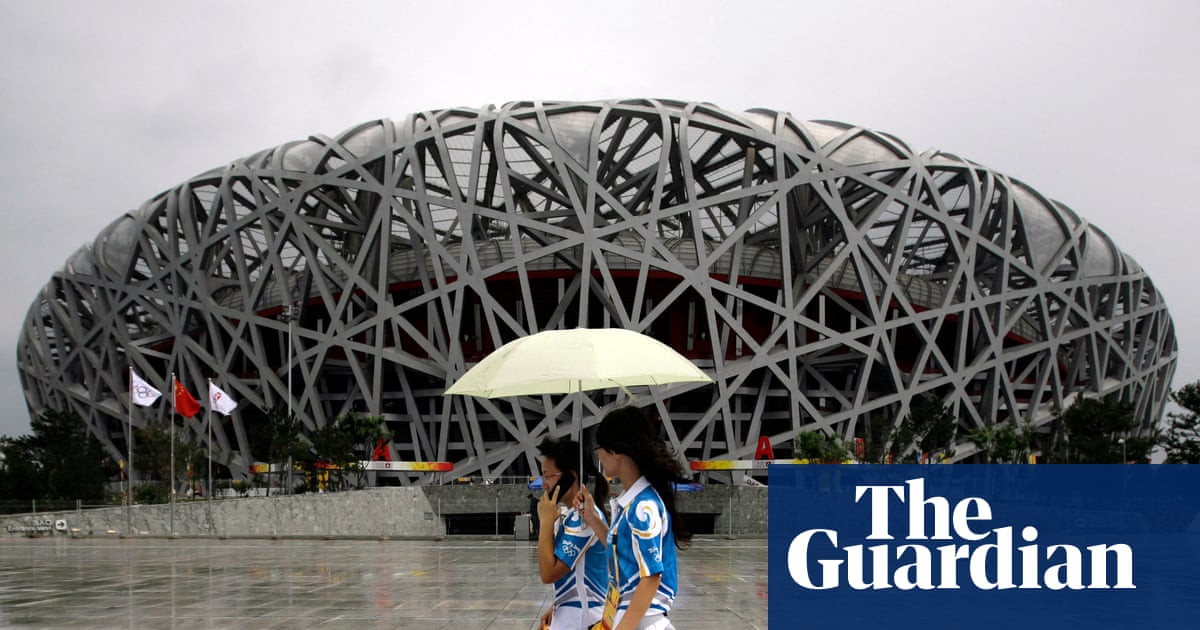

When the legendary Taiwanese rock band Mayday were due to perform in Beijing one evening in May 2023, some fans were worried that the rainy weather could affect the show. Mayday were taking to the stage in Beijing’s National Stadium, also known as the Bird’s Nest, built for the 2008 Olympics. Like the real-life twig piles that give the building its nickname, the stadium is built with an intricate and highly porous lattice, made of steel.

“Don’t worry too much,” reassured an article published by the official newsletter for China’s ministry of water resources. “The Bird’s Nest also has its ‘secret weapon’!”

The secret weapon is a network of capillary-like tubes that weave through the Bird’s Nest’s outer lattice, which are specifically designed to siphon away rainfall. The pipes channel rainwater into one of three underwater storage tanks, where it is filtered and prepared for recycling within the building. According to the water resources ministry, at least 50% of the stadium’s water needs – from flushing toilets to washing the running tracks to watering the lawns – can be met with the reused rainwater. In total, the water system surrounding the Bird’s Nest can treat 58,000 tonnes of rainwater each year.

The Bird’s Nest is one of the most pioneering examples of China’s focus on the practice known as “urban rainwater harvesting” (URWH), but it is not the only one. All over China, major buildings are constructed with a focus on URWH.

Across the road from the Bird’s Nest, the National Aquatics Centre is covered with a specially designed rainwater harvesting system that can collect approximately 10,000 tonnes of rainwater a year, equivalent to the amount used by 100 households.

According to the Beijing local government, the city reuses 50m cubic metres of rainwater each year. Along with other sources, such as runoff from bathrooms, more than 30% of Beijing’s water needs are met by reused water.

It is not just public infrastructure that uses URWH. In 2022 the drone company DJI unveiled a shiny new headquarters in Shenzhen. The two office blocks are topped with sky gardens and include an integrated rainwater harvesting system for irrigating the lawns.

China’s use of URWH is intimately linked to the “sponge city” concept, an urban planning strategy based on ancient water systems that was brought into the modern era by Yu Kongjian, a landscape architect who founded the influential architecture firm Turenscape.

Sponge cities use green spaces, wetlands and permeable paving, along with traditional drainage systems, to help mitigate flood risks, especially in China’s humid south.

But the concept of reusing the rainwater that is captured in sponge city designs is particularly pertinent in China’s dry north, which is blighted by seasonal droughts. Managing water flows across the country has challenged China’s rulers for millennia. From as early as the Qin and Han dynasties, there are records of ponds being constructed to store domestic rainwater.

“China has a special affinity for rainwater,” says Wang Dong, the director general of the ecological city studio at Turenscape. In traditional Chinese homes, buildings are situated around a central courtyard. Wang explains that in ancient times the rooftops of the buildings were designed to collect water, which represented wealth, and divert it into the home’s interior rather than letting it flow away. In this way, wealth from all directions could be stored in the family home.

“Chinese people have long highly valued the utilisation of water resources, it is deeply embedded in our DNA,” Wang adds.

In 1995 the Chinese Communist party (CCP) hosted China’s first modern-day national seminar of rainwater utilisation in Lanzhou, a dry northern city that abuts the Gobi desert. In the following decades, URWH started to be incorporated into official engineering codes, with the 2008 Olympics being the perfect opportunity to showcase these designs. As Yu’s “sponge city” concept grew in popularity in the 2010s, and was adopted as an official strategy by the Chinese government in 2014, URWH became fundamental to China’s national planning. Now, the government’s official target is for 70% of rainfall in sponge cities to be reused.

According to Chinese media reports, the size of China’s URWH industry, including products such as storage tanks and filtration systems, reached 126bn yuan (£13.5bn) in 2023, with further growth expected.

Reusing the rainwater is not as simple as collecting it and pumping it into the building’s pipes. Effectively storing, treating and repurposing the water requires designing buildings with a parallel “grey” water system to keep the recycled fluids separate from purified drinking water.

But it is a challenge that architects relish. In China, designs that absorb and reuse rainwater effectively are “absolutely fundamental to the development”, says Dan Sibert, a senior partner at the architecture firm Foster and Partners, who has worked on several projects in China that incorporate URWH, such as the DJI headquarters in Shenzhen. “It’s not a sort of add-on that comes a bit later on.”

He says: “For us as architects, what’s really exciting is how do you utilise the thing that could be a constraint to make the lives of the people in the buildings and around the buildings much better?”

As well as being good for the environment, Sibert says URWH enhances the experience of people using China’s modern buildings, because they feel they are in an ecologically friendly space. “If you’re flushing the toilet using grey water, it’s good that people know that,” he says.

Additional research by Lillian Yang and Jason Tzu Kuan Lu