Good morning. The future of Iran hangs in the balance, with Donald Trump weighing military action. India has urged its citizens to leave the country by any available means of transport. My colleagues are keeping an eye on developments in Tehran and Washington. Here is a comprehensive look at the options the US president has in his arsenal.

Labour has emerged as the theme for today’s newsletter. The government has urged quick commerce companies to drop the 10-minute tag because of safety concerns for gig workers. But first, where’s the future for Indian employees?

Job hunt

A challenging external environment is spelling trouble for India’s biggest export: people.

Donald Trump’s America First sentiment has fuelled significant anger against Indians working in the US. Not only have individuals, especially those on H1B visas, been affected by the continued uncertainty and constant changes in rules and regulations, but leading companies such as FedEx, Google and Microsoft with Indian-origin CEOs are also facing anti-India rhetoric. Threats of violence against south Asian people increased 12 per cent in the year to November, according to an analysis by advocacy group Stop AAPI Hate and counterterrorism company Moonshot, and the online use of slurs against them rose by 69 per cent.

The anti-immigrant backlash against Indians is not limited to the US. In recent months, Canada and Australia have tightened scrutiny of Indian visa applicants because of alleged higher levels of fraud. These developments not only impact livelihoods but also have a significant adverse effect on India’s economy, because the country’s biggest exports are its people. For more than a decade, India has been the world’s biggest recipient of inward remittances, and this number has been growing very quickly. In 2025, Indians abroad sent home more than $135bn, according to data from the Reserve Bank of India — a number that has more than doubled in the past eight years.

Indians seeking refuge from dimming prospects abroad may not find it easy back home either. The country’s IT industry, which is one of the largest employers in the organised sector, was a safe harbour for white-collar workers. But prospects there are shrinking. TCS has slashed more than 30,000 roles in the past two quarters, while the number of employees in HCL Technologies has remained flat. The only meagre increase in the last quarter has been in Infosys, which added just 5,000 employees — a relatively small figure — to its massive workforce of more than 320,000.

These grim numbers are reflected in most other sectors too. In a piece in the FT last week, former RBI governor Duvvuri Subbarao wrote about the worrying prospect of jobless growth in India, particularly in manufacturing. The rise in gig employment, often sought as a last resort, is a function of lack of opportunities elsewhere. The central bank’s data on the massive rise in consumer credit, and the consistent fall in deposit growth rates too, bear this out. A vast majority of Indians are struggling to pay their bills and save any money.

The more troubling aspect is that none of this is really a new problem. Successive governments have been able to do very little on the ground to solve this, and have resorted instead to torturing data to show improvement. The rise of AI and other technological innovations will only make this worse. Much was written about India’s demographic dividend in the early 2000s. For the economy, the prospects of that payout are looking increasingly slim. And for Indian jobseekers, stuck between worsening conditions both at home and abroad, the future is challenging.

Do you think India still has a demographic dividend? Where do you think the next wave of job creation for Indians will be? Hit reply or email me at indiabrief@ft.com

Recommended stories

Can Wikipedia survive?

China reported a record trade surplus of $1.2tn for 2025.

Banks hit back at Trump’s plan to limit interest on credit cards. Also, his “unpredictable” policies have investors diversifying from the US.

Japan has fallen for its new prime minister.

Inside the race to build the next generation of jet engines.

Where to find Rome’s last truly authentic wine taverns.

Slow and steady?

India’s quick commerce companies have been told to drop the promise of 10-minute deliveries, after the government warned that the safety of delivery workers was being compromised in their need to rush.

The move was an uneasy conclusion to weeks of agitation and argument between delivery companies, gig workers and customers. The debate was framed by many as capitalism versus socialism (because making sure gig workers don’t get into road accidents is apparently a socialist proposition). Zomato (now Eternal) founder Deepinder Goyal took to social media and appeared on popular podcasts to make his case.

But despite dropping the 10-minute tagline, operations in the industry have remained much the same. The platforms, two of which are publicly held, are burning money in order to acquire and service more customers, because there really is no room for three players in the industry. Eternal infused more than Rs2.6bn ($288mn) in Blinkit in 2025, amid rising losses. In December, Swiggy raised Rs100bn through institutional placement to fund this business. Zepto, which is privately held and valued at $7bn, raised nearly $2bn during the year, according to media reports. The missing piece in the capitalism argument is where are the profits.

The 10-minute delivery phenomenon began during the pandemic and has since continued to grow. Even though big Indian metropolitan cities are the companies’ biggest markets, they now also operate in small cities and Tier 2 towns. While the proposition was catchy at the time of launch, I find it hard to believe that a difference of minutes is a major factor for users. Customers are fickle and value conscious, and they will simply use the platform that offers them the best rates.

In many ways, quick commerce is a snake eating its own tail. For the three players, having invested so much already, the business is too sweet to spit and too bitter to swallow. The government’s advisory is unlikely to change much for gig workers, who will still have to follow a punishing delivery schedule, even if the company is not advertising its services as 10-minute delivery. The only ones benefiting are the customers — for now. The platforms’ hope is that once people get used to the “convenience culture” they will be willing to pay more for it. Past experience in other industries (including my own, media) suggests that only a fraction will and even then not over a certain limit.

Go figure

India’s trade deficit widened narrowly in December, according to data released by the government yesterday, with exports growing marginally year on year, despite Trump’s tariffs. Here is a look.

$25bn

Trade deficit for December

$18bn

Service trade surplus

$850bn

Projected merchandise exports for the FY

Read, hear, watch

I have been trying to cope with the tedious Delhi winter and my daughter’s return to college by resorting to an old favourite, Nora Ephron’s I Feel Bad About My Neck. It’s an instant pick-me-up. (I miss that era when one could write self-deprecatingly without worrying about looking like a fool.)

I have also spent an embarrassingly large chunk of time this week playing The Untitled Goose Game. It’s a hilarious stealth puzzle in which you must get your goose to complete a list of objectives, annoying the poor inhabitants of an English village in the process. The goose is an absolute menace, and the only person who can derive some joy from it is the player. What’s not to like?

Buzzer round

Which company’s original name was Blue Ribbon Sports and was initially started to distribute Onitsuka Tiger shoes in the US? Hint — its logo kind of looks like a ribbon.

Send your answer to indiabrief@ft.com and check Tuesday’s newsletter to see if you were the first one to get it right.

Quick answer

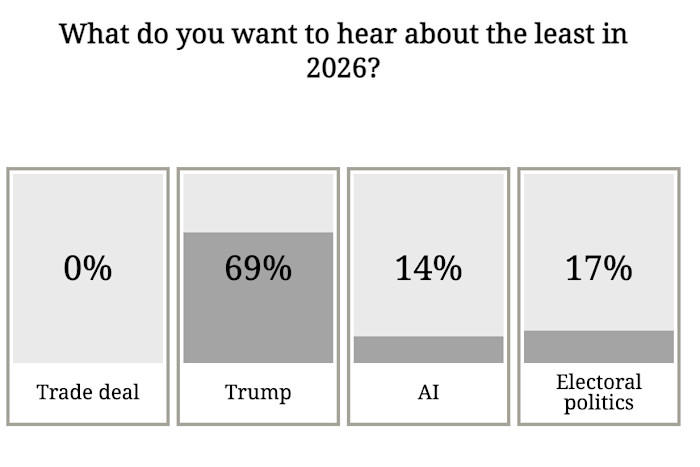

On Tuesday we asked what you want to hear about the least in 2026. Nearly 70 per cent of you want as little of Trump as is possible. If wishes were horses . . .

Thank you for reading. This India Business Briefing is edited by Tee Zhuo. Please send feedback, suggestions (and gossip) to indiabrief@ft.com.