For decades, Cambodia has shown its appreciation for its most important backer by naming major roads after China’s leaders. Mao Se Toung Boulevard has been on the map for 60 years, while Xi Jinping Boulevard was unveiled in 2024.

Now, Cambodia may be ready to bestow the same honour on a US president.

Cambodia is considering renaming National Route 4, the 225km-long highway that connects capital Phnom Penh with the port city of Sihanoukville, after Donald Trump, in one of the strongest signs yet of its intention to build warmer ties with Washington.

Spooked by US tariffs and a border conflict with mightier neighbour Thailand, Cambodia is looking to repair relations that have been strained by China’s commanding influence in the south-east Asian country. Its efforts illustrate how smaller countries are trying to position themselves as the US president disrupts the global trade order and ratchets up tensions with China.

“Cambodia sees America as a sort of guarantor of its own sovereignty facing the threat from Thailand, and America sees Cambodia may shift its position,” said Pou Sothirak, distinguished senior adviser at the Cambodian Center for Regional Studies and Phnom Penh’s former ambassador to Japan.

“This also fits into [Trump’s] containment policy of China,” he added.

Often labelled a Chinese satellite state by analysts, Cambodia was long seen by the US as a lost cause as Washington sought to limit Beijing’s economic and strategic influence in the region.

The US suspects that Cambodia hosts a Chinese naval base in Ream, located strategically in the Gulf of Thailand. Both Cambodia and China have denied that Beijing’s naval forces are using the base.

But Washington saw an opening when strongman Hun Sen, who governed for nearly four decades, handed over the premiership to his son Hun Manet in 2023.

A graduate of West Point Military Academy and a UK-educated economist, Hun Manet has engaged with the west far more than his father did. In recent weeks, the US has lifted an arms embargo on Cambodia imposed in 2021 and agreed to resume joint military exercises suspended nearly a decade ago.

“There’s new thinking in Washington DC . . . and Hun Manet understands the importance of the US in the regional context,” said Sothirak.

Trump’s tariffs provided another impetus for Cambodia to woo the US, which buys 40 per cent of Phnom Penh’s exports. The country is a top supplier of garments and shoes to American brands such as Nike. Trump initially threatened Cambodia with 49 per cent tariffs in April — the second-highest after China — before lowering them to 19 per cent.

When a long-simmering border dispute with Thailand erupted in armed conflict in July, Trump intervened and negotiated a peace deal, brandishing threats of higher tariffs — and earning a nomination from Phnom Penh for the Nobel Peace Prize.

After hostilities broke out again, the two sides agreed a ceasefire and ministers from both sides met last week in China, which pledged to “provide all necessary assistance and support”.

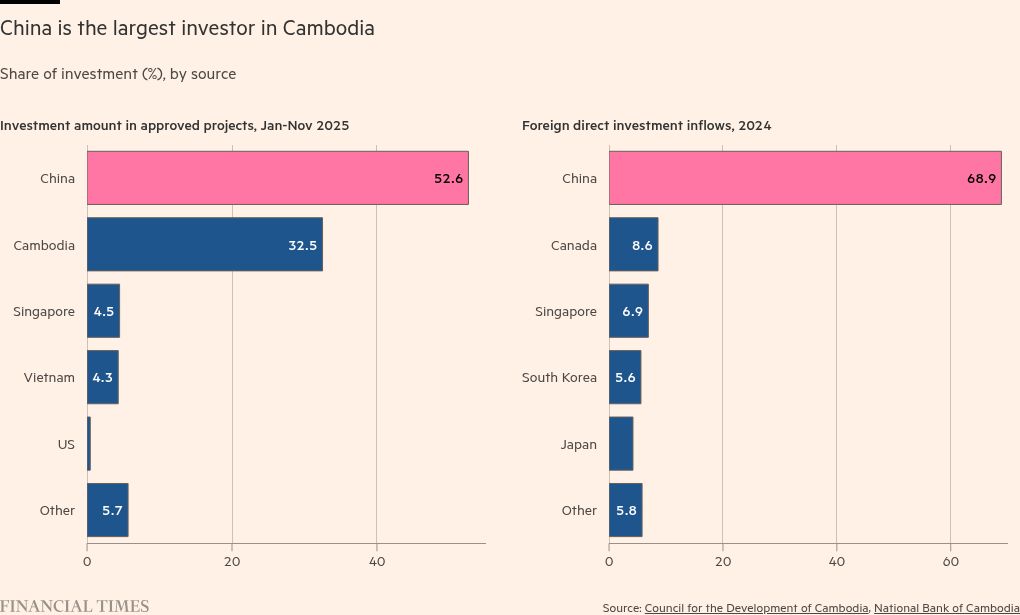

Still, navigating the relationship could prove to be tricky for Cambodia, which counts on Beijing as its largest investor, donor and trading partner.

In the first 11 months of 2025, China accounted for almost 53 per cent of total investment of $9.5bn, while the US accounted for just 0.44 per cent.

Since 1998, Beijing has helped build roads, airports, hospitals and other infrastructure in a country ravaged by decades of civil war. In just over a decade, the skylines of the capital Phnom Penh and several other cities have been transformed and connectivity improved, directly or indirectly through Chinese funds.

Even the country’s most important export industries are dominated by Chinese investors. More than 60 per cent of the members of Cambodia’s influential garment, footwear and travel goods association are from mainland China. These are the companies that are hired on a contractual basis by American groups such as Nike to produce branded products.

“China has been a great financial ally to Cambodia. They have helped build the country,” said Anthony Galliano, group chief executive of Cambodian Investment Management and a vice-president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Cambodia.

“China has invested in this country heavily, to give them credit, where the US hasn’t,” he said.

Cambodia has to find a way to strike a delicate balance between the US and China, Galliano added. “They need both the largest export market, and the largest FDI investor . . . because one affects the other. If the export market goes away, the imports from China go away and the FDI investment into factories goes away.”

Trump’s more pragmatic approach may help relations, some analysts said. Joe Biden’s administration cited democratic regression and Beijing’s creeping military presence for the 2021 arms embargo.

“They [previous administrations] talk a lot about democracy . . . I think Trump understands the real situation in Cambodia,” said Chea Thyrith, spokesperson for Cambodia’s senate and the still influential Hun Sen.

For now, Cambodia remains a steadfast supporter of China.

In a statement, China’s foreign ministry referred to the two countries as “ironclad friends” that “support each other and share weal and woe”.

It added that the Ream naval base “belongs to Cambodia”, while a joint support and training centre was “a product of co-operation” consistent with “relevant international law and international practice”.

The US state department did not respond to a request for comment.

A more amicable relationship between the US and Cambodia may yet prove difficult given China’s presence — as the highway that could bear Trump’s name illustrates.

Running parallel to National Route 4, which was constructed with US funding, is a new Chinese-built expressway that also connects Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville, cutting travel time in half to Cambodia’s gateway to international trade.

The port city is also a centre for online scam operations, which have come under increasing US scrutiny. In October, the US indicted Prince Group and its chair Chen Zhi, a naturalised Cambodian citizen, for running industrial-scale cyber scam operations that it said were robbing Americans of billions of dollars.

Ultimately, any rebalancing would carry huge risks. “Cambodia cannot be realistically neutral,” said Ou Virak, president of Phnom Penh-based think-tank Future Forum.

“Neither the US or China will allow smaller countries to stay neutral. It’s a much more polarised world.” Cambodia should be particularly cautious not to anger China as it “could lose its major backer”, he added.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong. Additional reporting by Joe Leahy in Beijing