Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

The writer is the author of ‘Chip War’

Shortly before Christmas the US Federal Communications Commission gave an unexpected gift to America’s drone industry. By adding all foreign-made drones and key components to its “Covered List” of equipment that poses an unacceptable national security risk, the commission de facto banned China’s DJI, the industry leader in drones. This opens the market to US drone companies. It may also mark a shift towards greater use of import restrictions in Washington’s tech competition.

The FCC — previously best known for regulating obscenities on TV — is now taking centre stage in the tech war. It has authority to ban imports of any communications equipment that it believes facilitates espionage or threatens critical infrastructure. From internet routers to drones, as the range of communication equipment increases so does the FCC’s authority. Congressional legislation has expanded its reach, arming it to take on technology challenges posed by China.

The FCC’s move comes as a counterpoint to President Donald Trump’s broader détente with China as the US tries to reduce its rare earth vulnerabilities. Yet Trump himself has also outlined a strategy of “drone dominance”, with the Pentagon planning to purchase 300,000 small attack drones by 2028.

The Russia-Ukraine War has exposed a “drone gap” in American defence production. Many US companies still rely on China for key components like batteries and motors. In 2024, China cut off battery sales to US drone companies, forcing makers like Skydio to ration battery sales.

The problem that US drone companies face is scale. China’s DJI is estimated to sell more than half the world’s cheap, first-person view drones. Because of this, China is also the leader in producing many key drone components. This provides major advantages. Companies can only justify developing specialised chips and other hardware if they can amortise the cost over many units sold. China’s market dominance has made it impossible for foreign companies to compete.

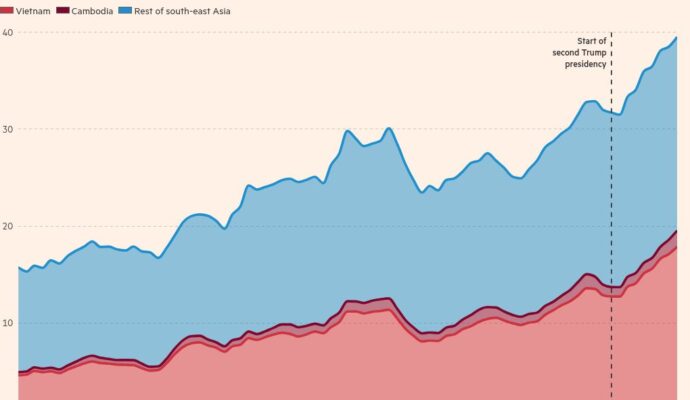

During the first Trump administration, the US tried to address this by imposing a 25 per cent tariff on imported Chinese drones. DJI quickly pivoted its production base for US sales to Malaysia. In 2024, Malaysia exported three times as many drones by value to the US as China did.

The ease with which China’s drone industry shifted production shows why globalised supply chains make tariffs a blunt and often ineffective tool.

Drones weren’t the only industry to relocate production. Now Trump’s trade officials are pushing other Asian countries to limit the rerouting of Chinese goods.

Although the US has leaned more heavily on tariffs (under Trump) and export controls (under Trump and President Joe Biden), the drone ban is not the first time America has banned Chinese tech imports. The first Trump administration prohibited use of Huawei’s telecom equipment, for example. The Biden administration banned the Chinese communication equipment and software used in connected cars, using the Commerce Department’s Office of Information and Communications Technology and Services.

Congress is now considering legislation to bolster the commerce department’s powers. Senior Republican legislators recently called on commerce secretary Howard Lutnick to use this authority against imports of Chinese equipment in sectors including data centres, robotics and the energy grid.

The FCC’s move against drones shows that the Trump administration has plenty of legal power should it choose to act. Beijing will not be pleased but its long history of forcing Chinese companies to buy local products will undermine any criticism it raises. This year, targeted import restrictions could look more attractive than blanket tariffs.