Alfiyan Elfatah spends four hours each day commuting between Jakarta’s far-flung periphery and his workplace in the heart of the Indonesian capital. The 31-year-old has endured the slog for eight years — but only now is he officially crossing the biggest city in the world.

Last month, the UN updated its list of the world’s biggest cities after changing its methodology for assessing huge conurbations. It looked beyond Indonesia’s own 11mn reckoning of Jakarta’s population, sweeping into its calculations a much bigger urban area covering sprawling satellite towns such as Bogor, where Alfiyan lives.

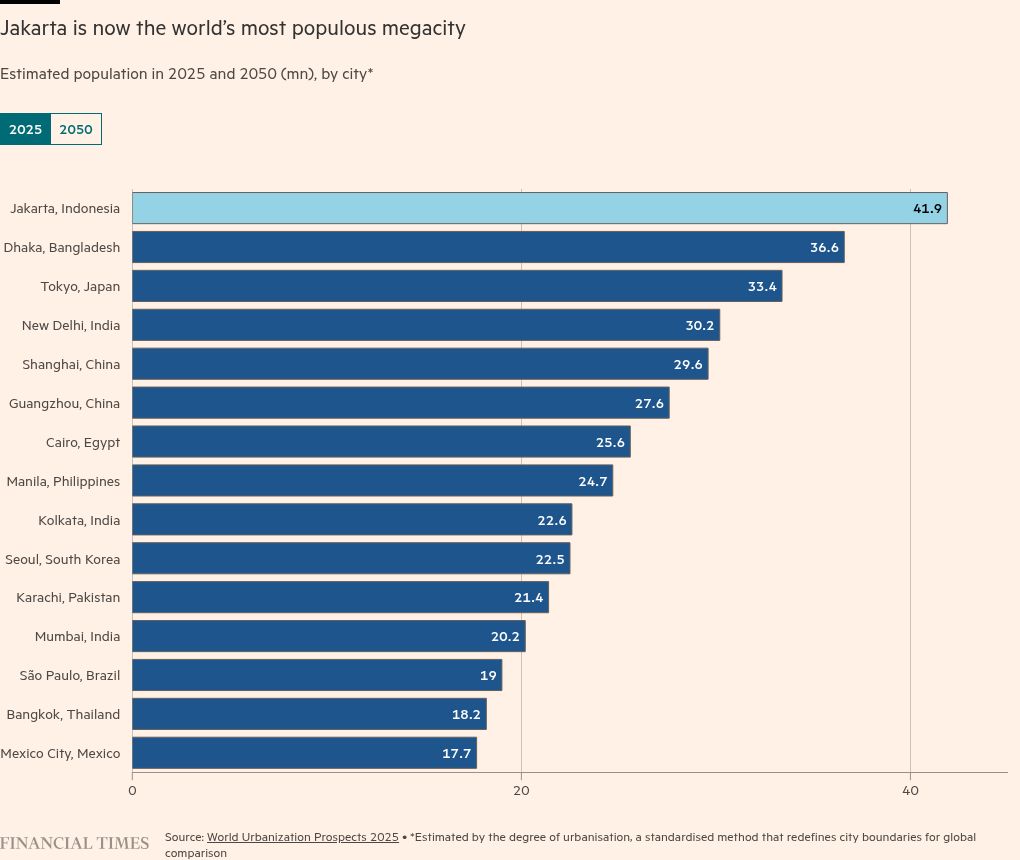

As a result, Jakarta is now estimated to have almost 42mn residents, overtaking greater Tokyo as the world’s biggest city, according to the UN.

Alfiyan, who travels to his marketing job at a hotel by motorbike, train and bus, sees little prospect of a halt to the capital’s growth. “Development is uneven. The economy is still centralised here, and we see Jakarta as far more developed,” he said.

The amended UN methodology pushed Jakarta to the top of the list from number 30 in 2018. It also makes Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, the world’s second-biggest city, with 36.6mn people. Cities in Asia dominate the list.

The Jakarta government and several Indonesian urban planning experts disagree with the UN definition, but say the ranking provides impetus to address the city’s challenges. Congested and polluted, the city known as the “Big Durian” after the famously pungent south-east Asian fruit is also sinking by up to 20cm annually.

“This is a wake-up call for the government to seriously address the problems of Jakarta,” said Azis Muslim, public policy expert at the University of Indonesia. “The challenge would be how to prepare infrastructure and improve the quality of life.”

Indonesia should accelerate efforts to ease traffic congestion in the city by improving interconnectivity with neighbouring cities and make housing more affordable, he said.

In an interview, Jakarta’s governor Pramono Anung also said the ranking “is not really important” by itself. “But the 42mn reported by the UN will encourage us to be prepared,” he said.

Pramono said he was committed to improving public transport for the 3.5mn to 4mn people he said commute every day into the city. He said he would allocate 30 per cent of Jakarta’s government budget, expected to total $4.9bn next year, to upgrade connectivity and other infrastructure.

However, his goals could be hindered by President Prabowo Subianto’s plans to cut funding for local governments as part of a broader plan to rein in costs and channel funds to a free meals programme for school children, expected to cost $28bn annually.

The central government’s transfers to Jakarta have been cut by $1bn for next year, making it more difficult “to maintain and manage the infrastructure”, said Pramono, but added that he intended to find other ways to raise funds.

Jakarta’s problems are reflective of other rapidly growing cities in Asia, which the UN says is now home to about half of the world’s 33 megacities — defined as urban areas with at least 10mn people.

Hidayat, 53, decided to move out of Jakarta a few years ago to Tambun, about 35km away. “It’s already overcrowded here in Jakarta. For people my age, we’re looking for more space . . . more comfort,” he said.

Yet the city remains the undisputed political and financial centre of gravity in south-east Asia’s largest economy. Last year, Jakarta — using Indonesia’s own definition of the city with 11mn residents — contributed about 16.7 per cent to Indonesia’s GDP.

That importance brings in commuters even though Jakarta’s infrastructure has not kept pace with the city’s expansion. While the number of buses and railway lines has grown, Pramono, the governor, said less than 25 per cent of the population used public transport in Jakarta itself, which is also badly connected to the surrounding urban areas.

Cici, 27, is one of the city’s millions of daily commuters, travelling two hours each way. She would rather work in her home town of Cikarang, 45km from Jakarta, but could not find a desirable job there.

“I actually want to rent a room close to the office, but housing prices are expensive,” she said. “I have to take the train, the very packed ones.”

By comparison, greater Tokyo, a vast urban area centred on the Japanese capital, has an extensive subway network, while Shanghai runs as many as 21 operating lines.

“The greater Jakarta area must be built as one system,” said Marco Kusumawijaya, director of the Rujak Center for Urban Studies in Jakarta. “If Jakarta is the only one developing, it is going to become increasingly expensive . . . even more unaffordable for people to live there. The number of commuters will rise.”

Recognising Jakarta’s mounting problems, Prabowo’s predecessor Joko Widodo announced ambitious plans to build a new capital city, selecting a site in the jungles of the island of Borneo. Development began in 2022 and is expected to cost $30bn.

Nusantara, as the new capital will be known, is targeted to be fully completed by 2045, though several government agencies are set to gradually relocate earlier.

However, since Widodo left office, the new capital has been put on the back burner by Prabowo, who is focusing on welfare programmes and has cut funding for its development. Any construction delays are set to mean the pressure on Jakarta will only worsen.

Pramono acknowledged the challenges but said Jakarta would remain the country’s centre of economic activity and retain its appeal for millions of Indonesians from across the archipelago.

“For me, Jakarta is a city full of dreams,” he said. “That’s why as a governor, I’m not against people coming to Jakarta, because that’s where hope and dreams are.”