After India’s worst travel meltdown in years left tens of thousands of passengers stranded this month, civil aviation minister Ram Mohan Naidu Kinjarapu stood up in parliament to declare that the country must break the duopoly that rules its skies.

“We need to have five big airlines,” he proclaimed after an operational failure at India’s dominant carrier IndiGo. “I want more players to be there in this industry. This is the time to start an airline in India.”

The minister’s call came after an exceptionally bumpy year for Indian aviation, with the IndiGo chaos and the fatal crash of an Air India jet exposing cracks in the world’s third-largest air transport market as passenger numbers surge and aircraft orders pile up.

India was “a lesson for any market suffering from concentration”, said Addison Schonland, co-founder of aviation consultancy AirInsight Group. “In the US and China, there are several peer-sized airlines that can step in to ease shocks. India doesn’t have that.”

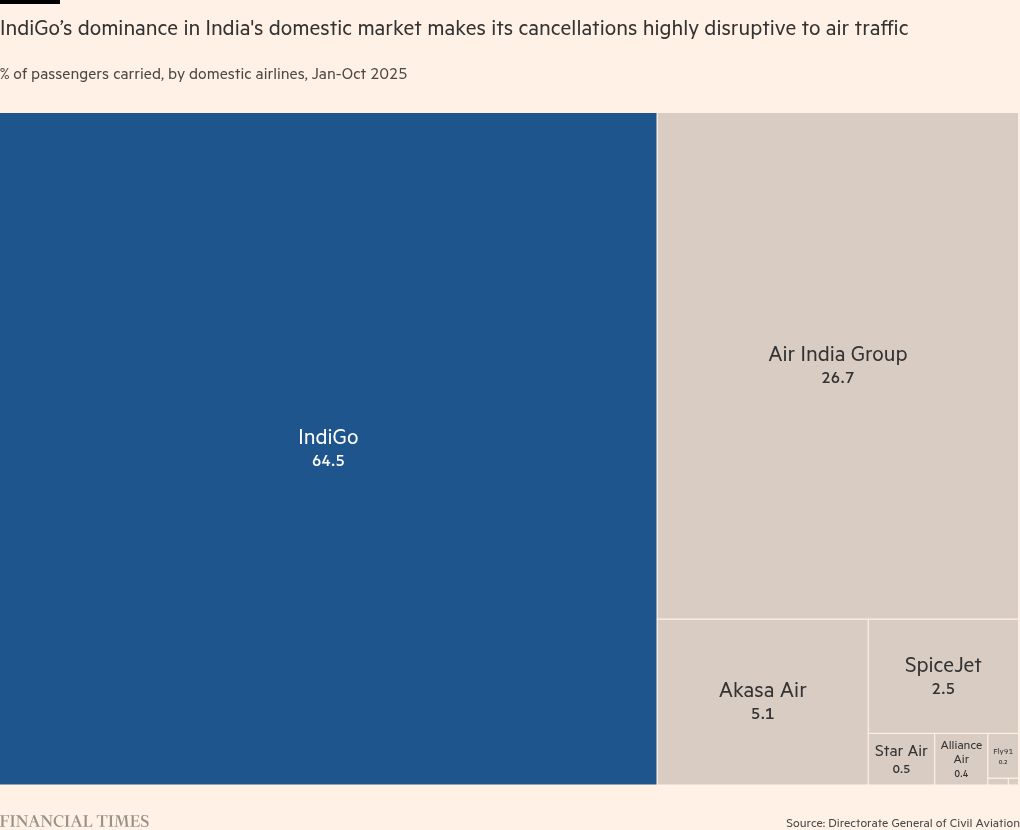

IndiGo controls 64.5 per cent of the market for domestic flights, while Air India makes up another 26.7 per cent. Barriers such as high sales tax on fuel have prevented challengers from entering the market, leaving flyers with few choices.

For years, IndiGo was able to maintain a reputation for ruthless efficiency and reliable performance. But it was knocked after a failure to prepare for new pilot fatigue rules led it to cancel more than 2,000 flights at the height of India’s busiest travel season.

IndiGo admitted to inadequately preparing for the rules, which were signposted almost two years ago and came into force last month. It faced anger not just from customers and New Delhi but also pilot unions who accused it of using the turmoil to force the government into a U-turn, suspending the regulations.

IndiGo’s chair, Vikram Singh Mehta, has denied that the carrier had “engineered the crisis” or “tried to influence government rules”.

That incident came as public confidence in air travel was already low. In June, a London-bound Air India plane crashed shortly after take-off in the western city of Ahmedabad, killing 260 people. The disaster hit Tata Group, which was more than halfway through a post-privatisation turnaround plan.

Air India has since been pulled up by the country’s civil aviation regulator for multiple safety lapses as it struggles to overhaul its fleet amid global plane delivery delays.

The final say on what happened to the Boeing Dreamliner from Indian investigators is pending. But a preliminary report sparked controversy after its ambiguous findings sparked a blame game, with some media reports suggesting pilot suicide as the potential cause — a conclusion vigorously contested by unions.

Schonland said India’s government had “fumbled the investigation” by leaving unanswered questions that fuelled speculation.

In his first public appearance since the crash, Air India chief executive Campbell Wilson in October told an industry event that the airline was “looking at how we can keep improving”.

He added that the initial probe findings “indicated that there was nothing wrong with the aircraft, the engines or the operation of the airline”.

Despite management assurances, the events over the past year mean that “people just don’t trust the airlines”, said one industry executive. Air India, IndiGo and India’s civil aviation ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

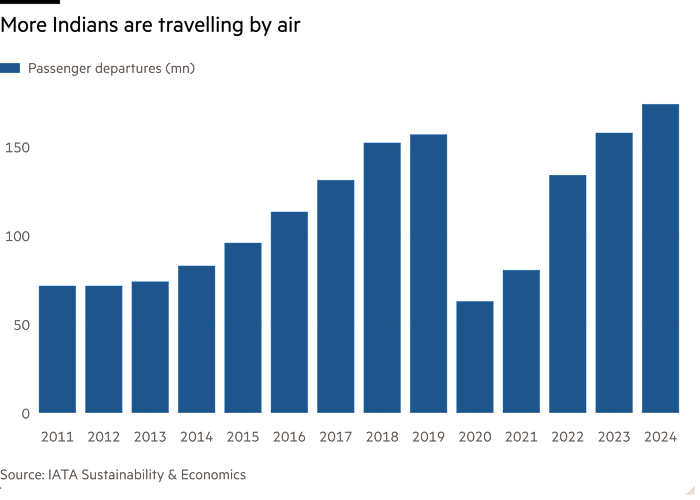

The number of people flying in the world’s most populous country is only growing. The International Air Transport Association has forecast that the annual number of passengers travelling into, out of or within India by plane will reach 425mn by 2044, almost triple last year’s figure.

New Delhi has been pushing for greater competition in the sector to give Indians more choice, but analysts doubt new airlines will take flight in India’s burdensome market soon.

Since 2004, more than 15 carriers have gone bankrupt, according to Iata. Aviation advisory and research group CAPA India estimates the country’s airlines lost $22bn in that time, with only IndiGo making a profit.

“If somebody is to come in now to start a low-cost airline in India you need $1bn minimum for the first five years,” said Kapil Kaul, chief executive of CAPA India. “There isn’t anybody knocking at the door. The cost of running an airline in India is not adequately compensated by fares.”

Many Indians have become accustomed to low-cost tickets that in real terms are 21 per cent cheaper on domestic routes since 2011, according to Iata. At the same time, the number of aircraft operating in India has more than doubled in the past decade to more than 800, while passenger numbers have also more than doubled.

A major drag is aviation fuel, which accounts for up to half of an Indian airline’s operating expenses, well above the global average of about 28 per cent, according to Iata. Kaul said many big Indian states slapped sales tax on fuel of between 20 and 28 per cent.

Pressure was compounded by the weak rupee, Asia’s worst-performing currency this year. About 70 per cent of airline costs were denominated in hard currencies, said Kaul.

With such formidable barriers to entry, experts believe the make-up of India’s air transport sector is likely to remain concentrated.

“If you do not relax some of them, whether it’s tax, fuel charges and so forth, it’s very difficult for the airlines to make money,” said Mayur Patel, aviation consultant at OAG, an industry data provider.

Perhaps more critical is whether India’s air industry infrastructure will be able to keep up with what Iata calls an “expected significant fleet expansion”.

As hundreds of aircraft ordered by IndiGo and Air India slowly get delivered, about 37,000 pilots and 38,000 technicians will be required over the next two decades to replace the many experienced crew members approaching retirement age.

“There’s a whole ecosystem that needs to be recalibrated,” said Patel. “If you build infrastructure and you cannot maintain your airspace control, then what’s the point?”