India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi gathered legislators from his ruling coalition in the halls of parliament this month to tell them to prepare for a “reform express” drive.

A few weeks later, lawmakers have wrapped up one of India’s busiest legislative sessions in years, as Modi has followed a string of domestic political successes by turning his attention to a spate of measures aimed at India’s fast-growing economy.

The country’s parliament approved proposals to remove limits on foreign direct investment in insurance and open the nuclear power sector to private players, while the government had earlier announced an overhaul of India’s customs duty regime.

In recent months, Modi’s government has also slashed the complex goods and services tax regime and enacted new labour codes, while the central bank has allowed Indian banks to expand their business into providing finance for mergers and acquisitions.

“Modi does a big thrust of reforms periodically, like a ‘big bang’, when the conditions are ripe,” said Baijayant Panda, vice-president of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party. “This is one of those moments.”

India’s veteran prime minister, who lost his outright majority in national elections last year has been buoyed by a string of rejuvenating victories in state polls, giving him more political capital for reforms.

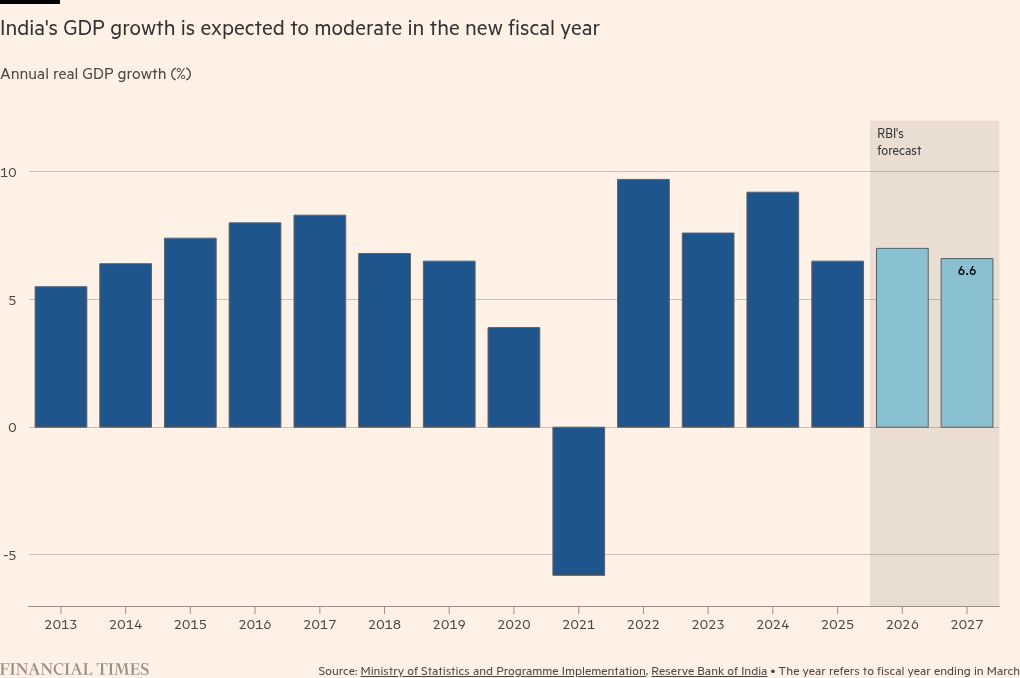

While India’s economy is still growing strongly, with annual GDP growth of more than 8 per cent in the most recent quarter, Modi is also trying to tackle mounting geopolitical challenges, including US tariffs of up to 50 per cent, and woo global investors to India as a manufacturing rival to China.

“Multiple things have created conditions for the government to push for certain economic reforms which were on the back burner,” said Rahul Verma, a fellow at the Centre for Policy Research think-tank in New Delhi, adding that Modi’s government had a breathing space after electoral wins in Maharashtra, Haryana, Delhi and Bihar last month.

Investors and economists have long urged New Delhi to cut red tape, relax labour laws and simplify taxation and compliance to help stimulate investment and boost growth.

Tax and labour reforms and moves to ease regulation could “reduce overall costs and complexities for businesses and investors”, said Gopal Nadadur, senior vice-president at The Asia Group.

The GST overhaul, which was years in the making, reduced four tax rates to two to help simplify pricing and spur consumption growth.

The labour code reform, which was unveiled in 2020 but not enacted because of pushback from opposition parties and trade unions, seeks to formalise the vast informal sector, reduce compliance burdens on some small businesses and expand social security coverage.

“Going forward, India has to do a lot more of what I call ‘governance stimulus’ which means ease of doing business, and that is what the government has started doing in the past few months,” said Pratik Gupta, chief executive of Kotak Institutional Equities.

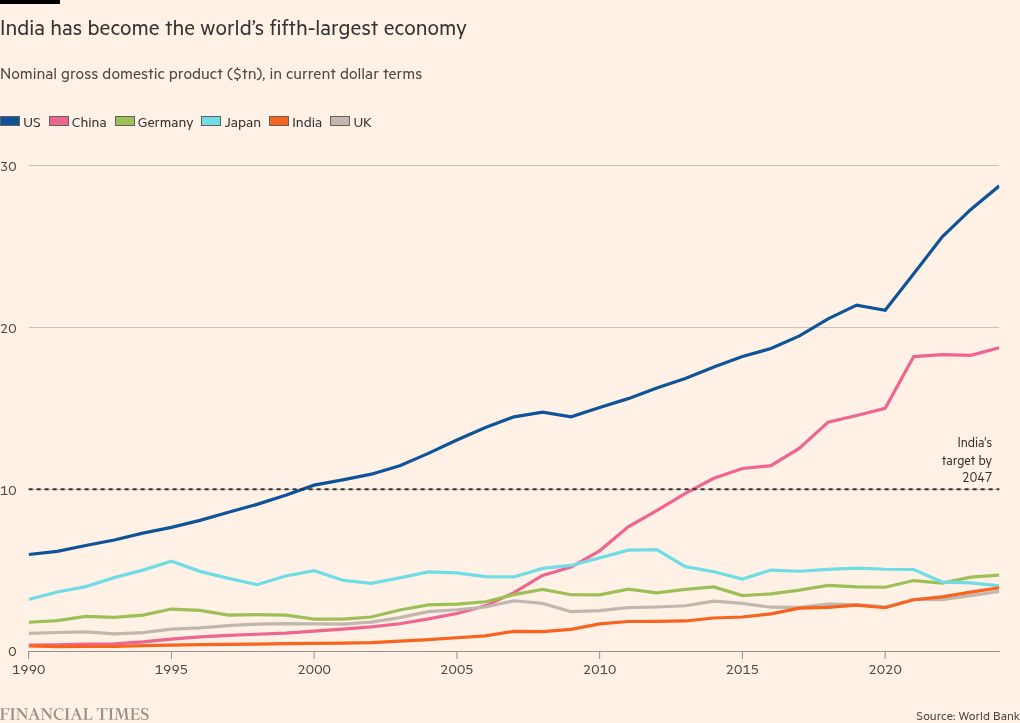

Blistering economic growth has also provided a tailwind for Modi, who has ambitions for India to become a developed economy by 2047, its centenary of independence.

Success would place him among India’s most consequential reformers since P.V. Narasimha Rao, who opened the economy to foreign investment and in 1991 dismantled the bureaucratic web known as the “Licence Raj”, lifting the government’s heavy interference across industries.

Achieving such a feat would require average annual GDP growth of about 8 per cent over the next two decades, according to economists.

Modi’s task has become only more arduous after US President Donald Trump doubled tariffs to 50 per cent on many Indian exports as punishment for purchases of discounted Russian oil. The Reserve Bank of India has forecast growth will moderate to 6.6 per cent next year.

But analysts believe Washington’s measures may have helped spur Modi to accelerate his reformist drive.

“The international context has changed so drastically,” said Delhi-based political analyst Pratap Bhanu Mehta. He said India was facing “probably the most significant crisis” in the past 25 years, with “a hostile China and a hostile United States”. The renewed impetus for reforms “is actually a response” to that, he said.

While US tech giants Amazon and Microsoft this month announced a combined $52.5bn of investment in India over the coming years, net foreign direct inflows are at three-year lows, according to Financial Times’ fDi Markets data.

And despite high-profile investments from companies such as Apple, manufacturing remains mired at about 17 per cent of GDP, well short of Modi’s 25 per cent target for 2025. Wage growth has also stagnated.

Arvind Subramanian, a former chief economic adviser to the government and author of A Sixth of Humanity, said the “real proof” of Modi’s reforms would be whether private investment “picks up”.

“Only this can be a sustainable engine of growth in the long run,” he said.

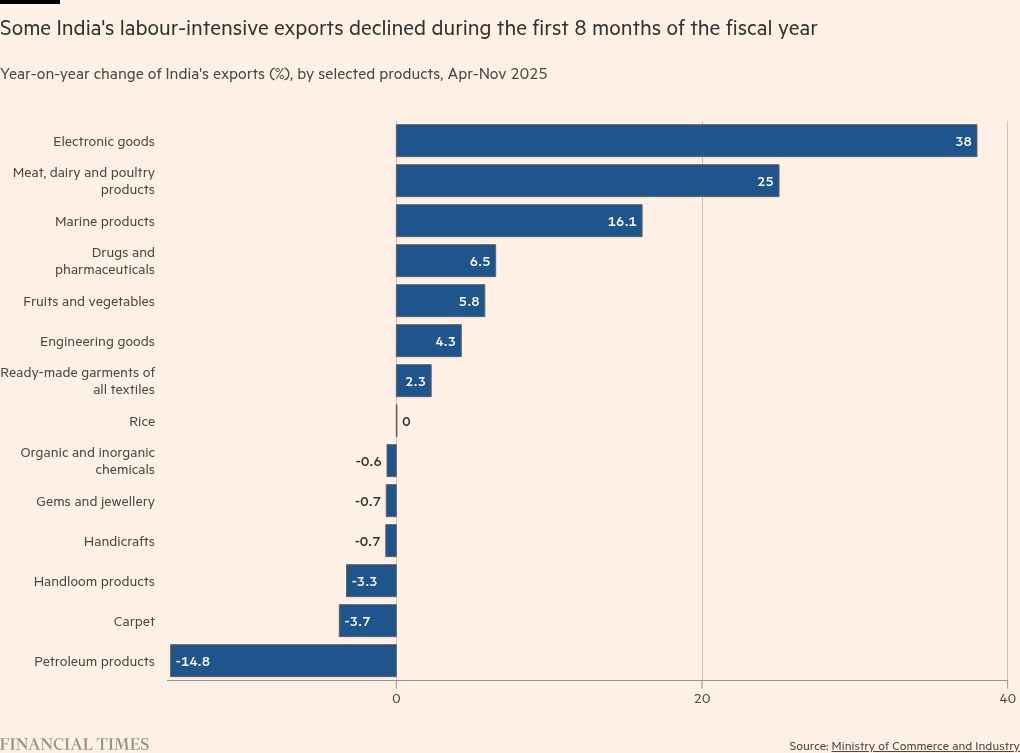

New Delhi’s negotiators have failed to find a breakthrough in trade talks with Washington, which could hurt labour-intensive sectors such as textiles.

Modi has also resisted opening up India’s agriculture and dairy markets to a flood of cheap US imports, which could threaten a voting bloc of millions of farmers and hand the opposition a boon ahead of four elections next year in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Assam and West Bengal.

The shift to focus on the economy comes after Modi’s second term was consumed by efforts to entrench the BJP’s Hindu nationalist ideology.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Ayodhya in northern India, where the prime minister last month presided over the official opening of the Ram Mandir shrine, a sprawling temple complex built on the ruins of a 16th century mosque that was razed by Hindu mobs in 1992.

“The religious agenda was an obsession, a distraction which became paramount and the policy reforms were neglected” during the 2019-2024 term, said Subramanian.

At the inauguration ceremony, Modi hailed Ayodhya as “the backbone of developed India” and suggested that the “day is not far” when India, currently the world’s fifth-biggest economy, would become the third-biggest.

“Modi delivered this for us. I cannot express in words how important this is,” said Neelam Sachar, a devotee who visited the temple soon after its opening.

“He can now do whatever work he needs to improve the economy.”

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong

India Business Briefing

The Indian professional’s must-read on business and policy in the world’s fastest-growing big economy. Sign up for the newsletter here