Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is founder and chief investment officer of Oasis Management

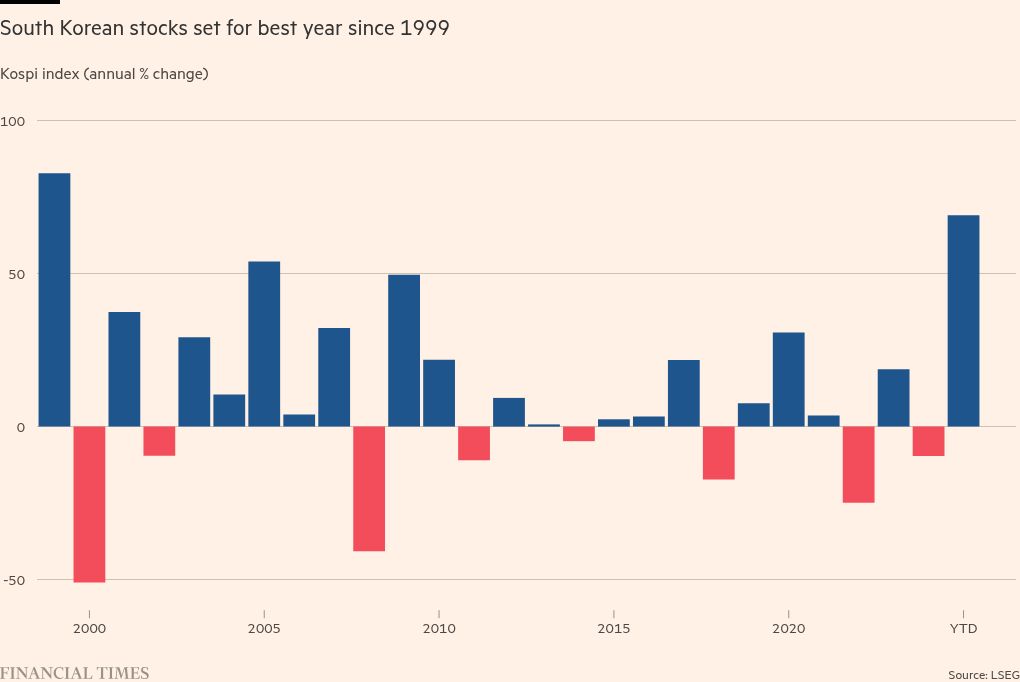

South Korea is among the best-performing major equity markets in the world this year, closing in on the strongest annual gains in a quarter century with the benchmark Kospi index up nearly 70 per cent in the year to date.

President Lee Jae Myung and his ruling Democratic party came to power in June with an aim to foster conditions to enable the Kospi to reach the 5,000 level. At the time, the target seemed like a moonshot given the index was trading around 2700. And yet, here we are with the index already at 4000.

A big factor behind the rise is South Korea’s corporate governance transformation, which I estimate has driven 40 to 50 per cent of this year’s returns, with the other largest factor being the global artificial intelligence-related rally.

Lee won office with a reform agenda aimed squarely at removing the “Korea discount” that has plagued local stocks despite world-class innovation at world-class companies.

Korea’s postwar economic miracle was driven by family-run “chaebols” that created global champions like Samsung, Hyundai, SK Group, LG Group, Lotte and others. Historically, mistreatment of minority shareholders by some companies was tolerated, in part because the population did not have a meaningful exposure to the stock market. But the pandemic changed everything. In the space of just a few years, the number of retail investors as a percentage of the voting population has risen from around 7 per cent in 2019 to more than 30 per cent in 2024, according to CLSA. In Korea’s robust democracy, improving household financial wellbeing through market returns is now a political imperative.

As an investor in Asia for the last 30 years, Korea’s invigorated focus on corporate governance is the most significant I have seen since the late Shinzo Abe’s dramatic “Three Arrows” economic policy was implemented in Japan. But the questions for investors in 2026 will be: Does the government have what it takes to truly transform Korea for the long-term?

The Korea discount stemmed from investors’ fears of abusive transactions, especially value-destructive mergers and acquisitions and related-party deals to support family empire-building and estate planning. The routine rubber-stamping of such transactions by compliant boards and a largely toothless shareholder base reinforced the notion that Korea was run by and for its largest shareholders.

In 2025, the government has been sprinting to change this. After an overhaul, the country’s corporate governance code now requires directors to consider all shareholders, not just the “company”. Cumulative voting, which enables minority shareholders to concentrate their votes on specific board candidates in proxy fights, is no longer optional for large listed companies with assets over Won2tn; if a shareholder with just 1 per cent requests it, boards must allow it. And there is now a cap on voting rights for any single shareholder — 3 per cent — for the election of board audit committee members, constraining the influence of controlling parties on these critical positions.

Companies are acting, too. Along with other investments in the country, my fund has a stake in SK Square, which has been an early leader in corporate governance improvement, narrowing the discount of its share price to net asset value from over 70 per cent to 50 per cent by divesting non-core businesses and buying back stock.

Further reforms are being planned in 2026 and beyond, including dividend tax reductions and possible changes to Korea’s inheritance tax, which is among the highest in the OECD. A new bill proposed by Representative Lee So-young has suggested measures to ensure controlling shareholders do not artificially depress the value of their company’s shares to reduce inheritance and gift tax. Regulators also are finally calling out and blocking abusive deals.

Of course there is more Korea could do. Establishing mandatory tender offers for the shares of minority shareholders upon change of control would be a positive step. Strengthening discovery in litigation would help protect minority shareholders when court intervention becomes the last line of defence. It also would be encouraging to see the National Pension Service, Korea’s largest investor with over $900bn in assets, vote more actively to support these improvements.

Korea’s experiment is one the world should watch closely. If the country succeeds in a sustained re-rating of its equities by reforming its corporate governance landscape, it will offer a powerful blueprint for other economies.