In cutting-edge Microsoft data centres, racks of chips used to train AI models sit idle. “The biggest issue we are now having is not a compute glut, but it’s power,” said Microsoft’s chief executive Satya Nadella during a recent podcast interview.

The topic has been top of mind in a year when big tech “hyperscalers” — Amazon, Google, Meta and Microsoft — have set out plans to spend more than $400bn in capital expenditure.

That outlay, mainly on data centres, has triggered market fears of an AI-fuelled bubble. Big tech groups have been undeterred, arguing that demand outstrips supply.

Hyperscalers are seeking to power their own workloads, but also supply Anthropic, OpenAI, xAI and other AI developers looking to train large language models (LLMs). These models underpin a host of tools that promise to transform industries.

Big tech stocks have risen as a result, but if computing supply is constrained by a lack of power, the AI “bubble” could deflate.

OpenAI alone has signed infrastructure deals totalling more than $1.4tn, amounting to an estimated 28GW in capacity over the next eight years. Chief executive Sam Altman has characterised the power crunch as existential.

“A certain risk is if we don’t have the compute, we will not be able to generate the revenue or make the models at this kind of scale,” he said recently.

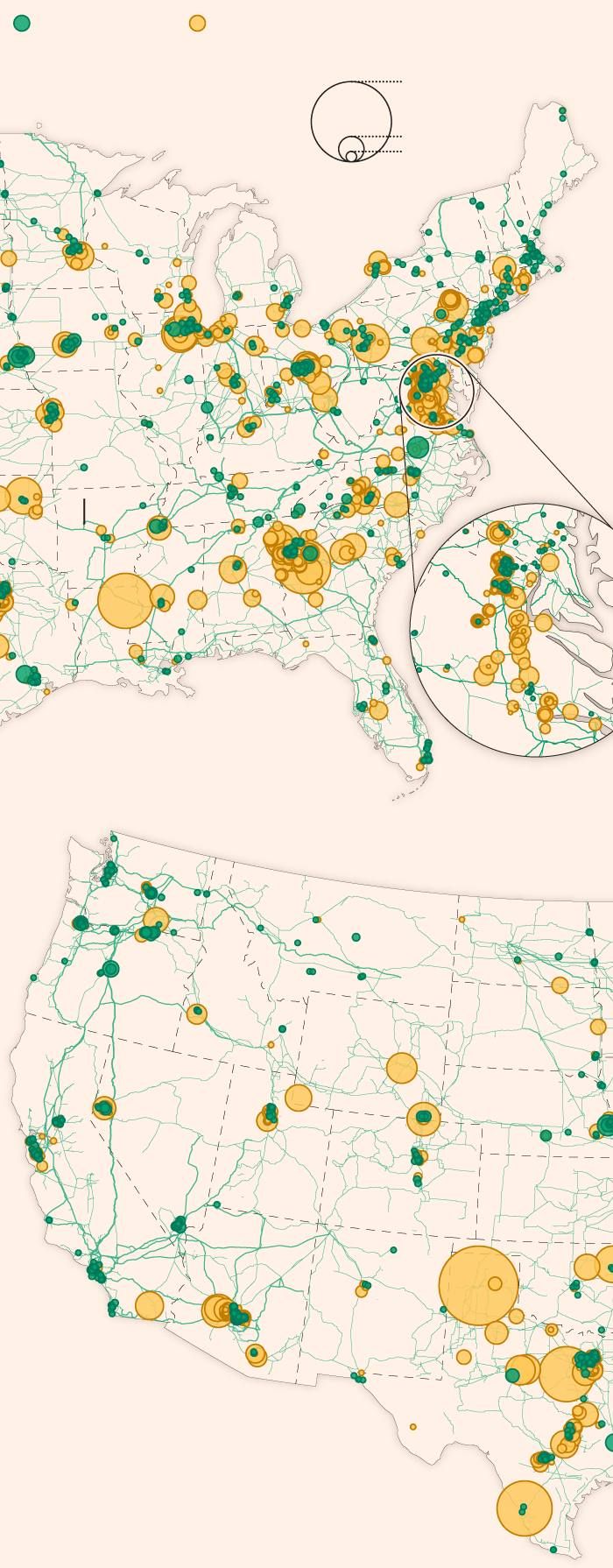

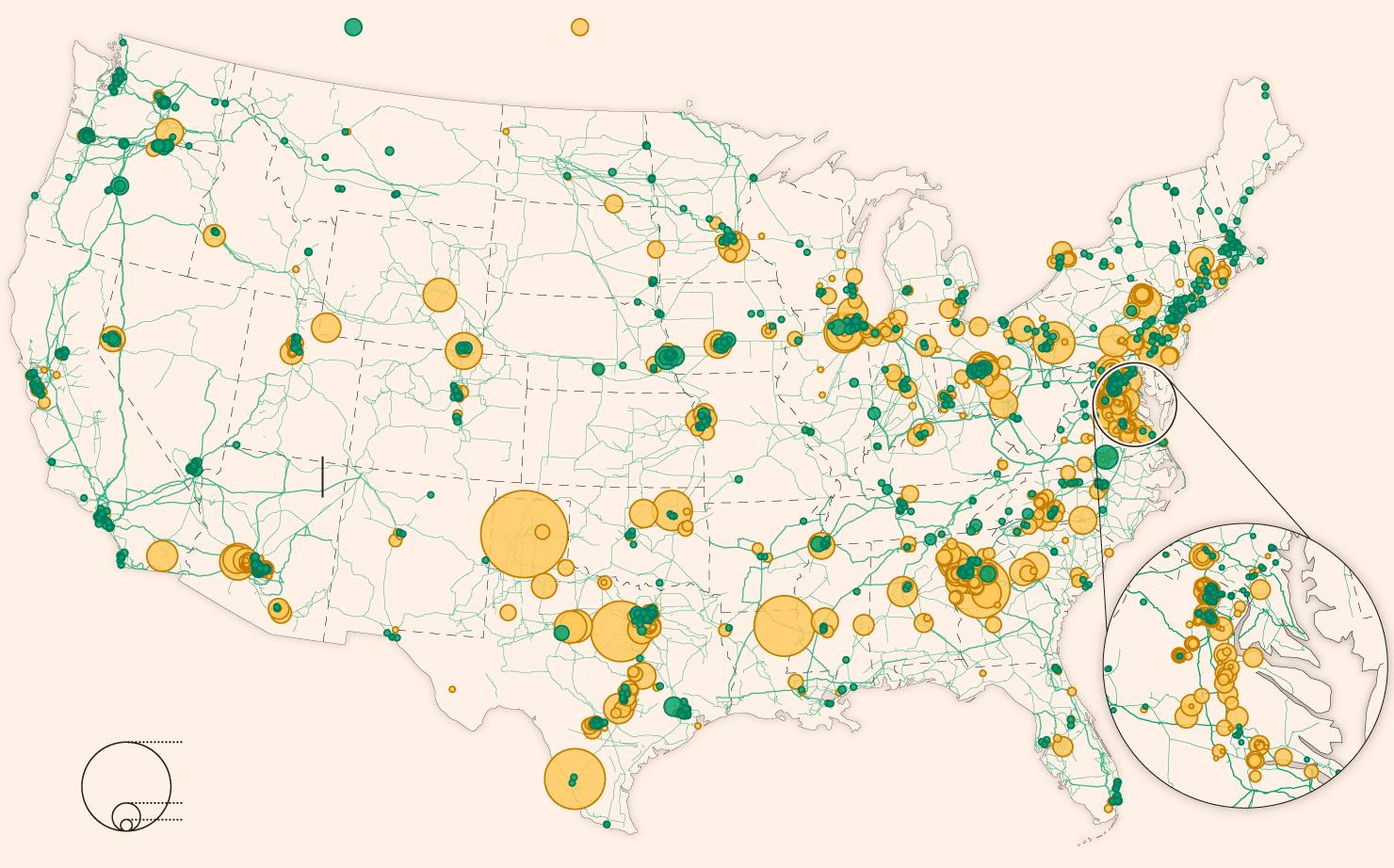

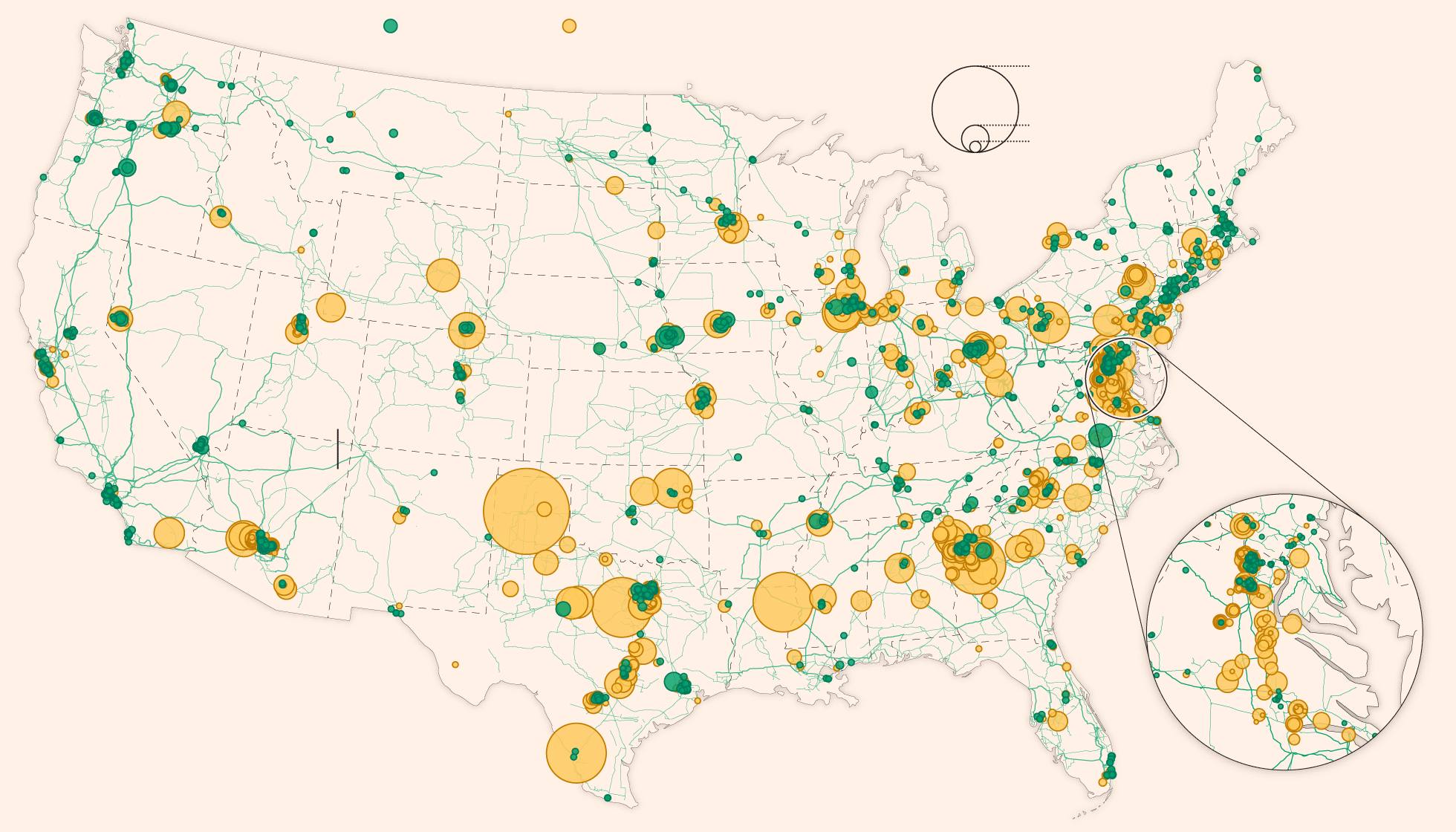

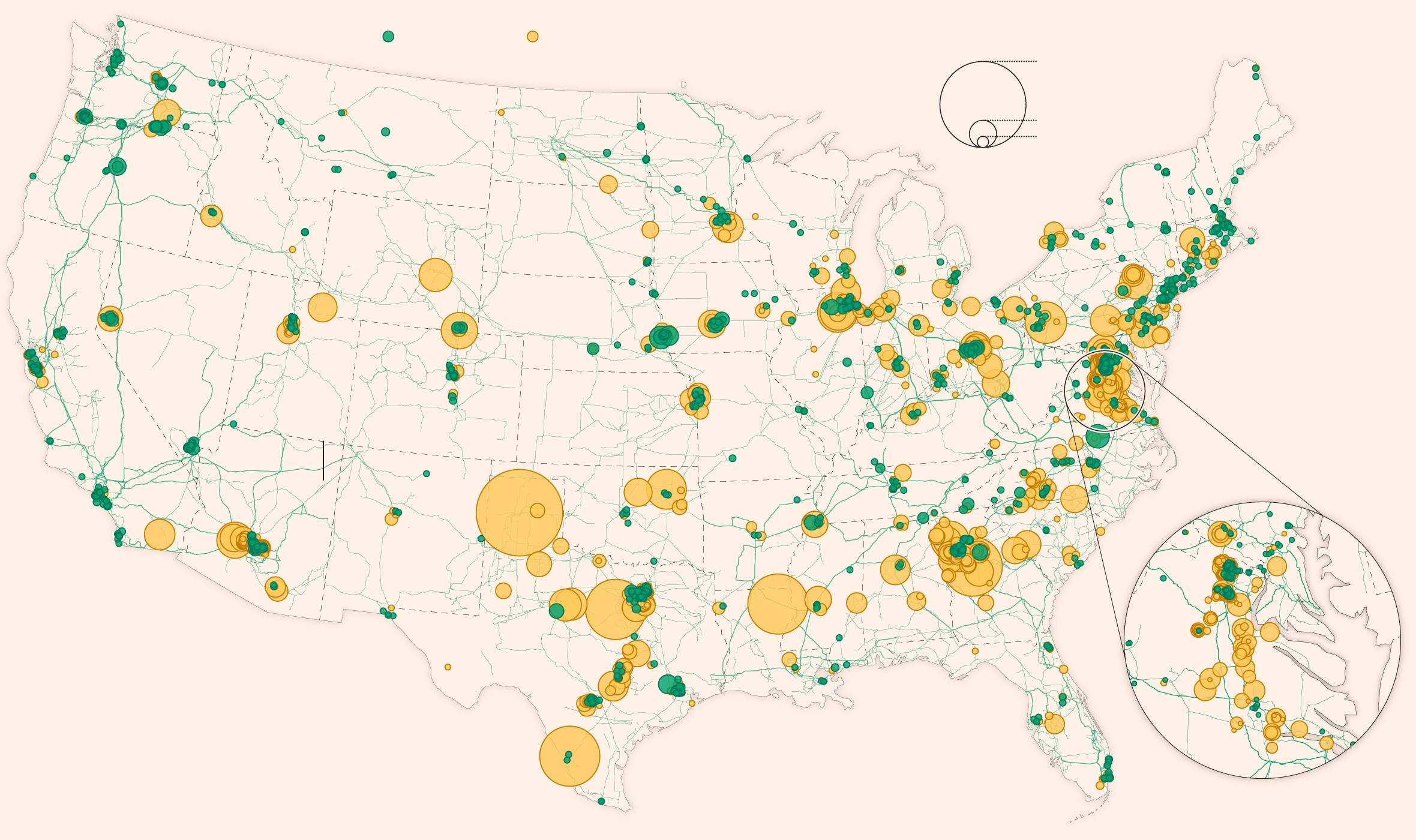

New data centres are expected to draw significantly more power

Power lines

Virginia has the densest cluster of operational data centres

Multiple gigawatt-scale projects are planned in southern states

Virginia has the densest cluster of operational data centres

Power lines

Multiple gigawatt-scale projects are planned in southern states

Virginia has the densest cluster of operational data centres

Power lines

Multiple gigawatt-scale projects are planned in southern states

Virginia has the densest cluster of operational data centres

Power lines

Multiple gigawatt-scale projects are planned in southern states

Need for speed

Silicon Valley has cast its wager on AI as both a source of future economic gains and a matter of national importance. Tech companies say they are racing against China to build artificial general intelligence — systems that surpass human abilities.

As hyperscalers expand and deploy more advanced chips, the pressure on energy supply is intensifying. In October, OpenAI wrote an open letter to the US government urging it to set an ambitious target of building 100GW a year of new capacity.

“In 2024, the PRC [People’s Republic of China] added 429GW of new power capacity — more than one-third of the entire US grid, and more than half of all global electricity growth. The US contributed just 51GW, or 12 per cent,” the company noted.

Tech groups have rapidly expanded key sites over the past 18 months

Amazon Project Rainier

OpenAI Stargate

Replay

While constrained by US curbs on accessing Nvidia’s most advanced AI chips, Chinese developers have made strides. DeepSeek released its powerful R1 model in January, comparable with US rivals despite being developed at a fraction of the cost and computing power. Chinese companies also receive subsidies to offset the impact of trade barriers.

The White House has responded with a sense of urgency. US President Donald Trump set out an action plan in July to “win the AI race”, adding that “from this day forward it’ll be a policy of the United States to do whatever it takes to lead the world in artificial intelligence”.

And American tech companies are ploughing ahead.

The power gap

After more than two decades of flat or anaemic growth, US power demand is now surging.

Electricity usage is projected to rise by an average of 5.7 per cent a year to 2030, based on forecasts from utility companies. Though some of this demand is due to reshoring activity and a broader shift to electrifying buildings and transport, more than half of the expected increase stems from the rapid build-out of AI data centres, according to consultancy Grid Strategies.

Even if these projections prove overstated, conservative estimates still far exceed recent trends, requiring substantial investment in grid capacity to accommodate new loads.

But boosting the US power grid is an enormous and time-consuming task due to a complex web of regulatory, financial and supply chain challenges.

Interconnection queues — backlogs of projects waiting to plug into the network — have become a major chokepoint, slowing the rollout of new power capacity and leaving data centres facing lengthy delays.

PJM, the largest grid operator in the US and home to “data centre alley” in Virginia, is under particular strain. The average time from filing an interconnection request to achieving commercial operation now exceeds eight years, according to energy think-tank RMI.

Nationally, the problem is compounded by developers approaching multiple utilities in search of the lowest price. This leads to so-called phantom data centres — duplicate proposals that further bloat queues and make it harder for utilities to prepare for future demand.

“There isn’t a significant barrier to entry [for speculative builders]. So one of the biggest challenges is finding out how much demand is real,” said Bobby Hollis, vice-president of energy at Microsoft. “There are a lot of participants who don’t know what goes into building a data centre . . . [And] few opportunities to filter out the noise.”

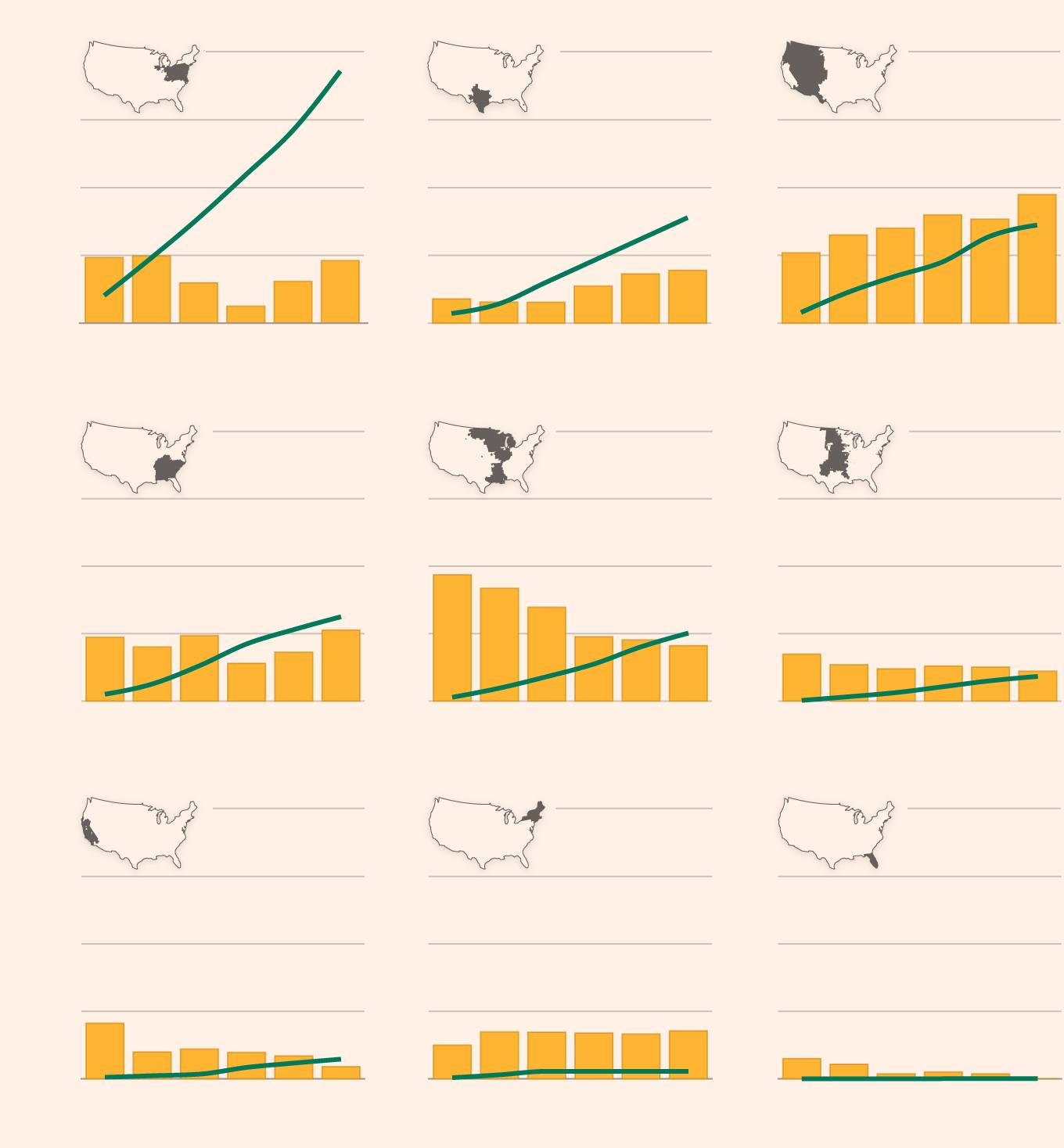

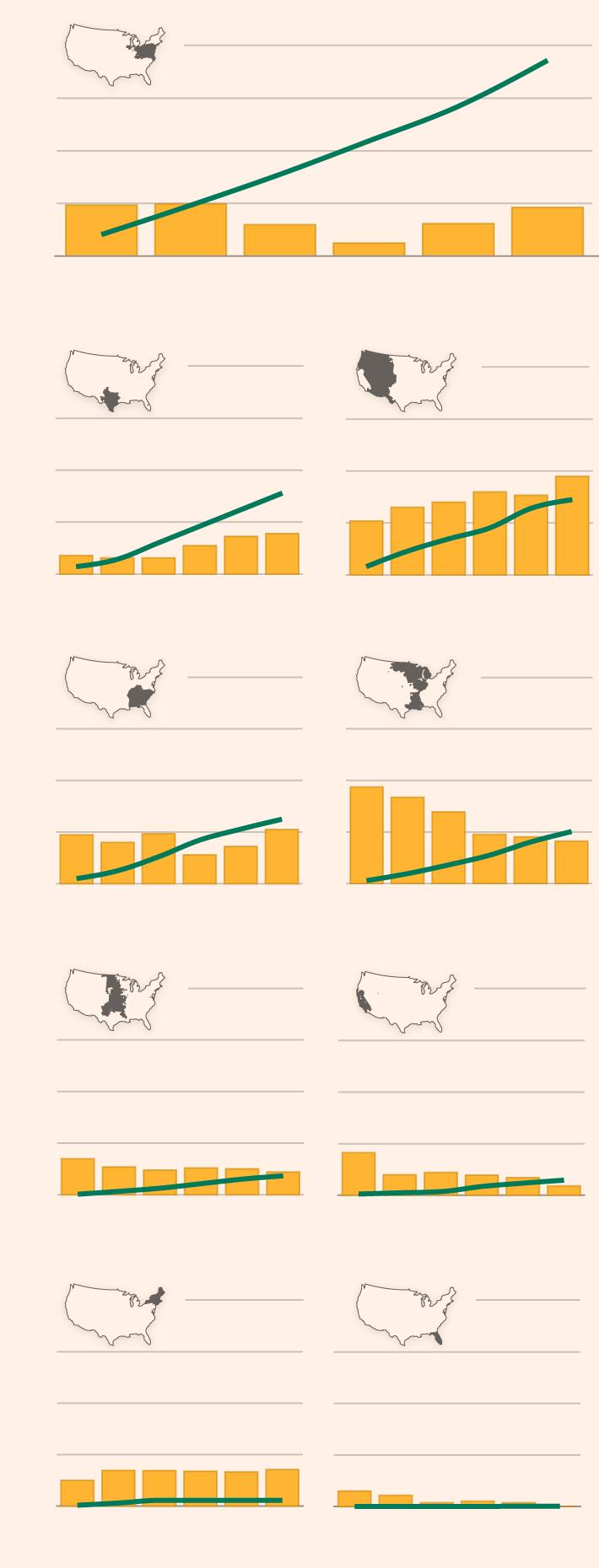

In parts of the US, the gap between new data centre demand and spare grid capacity is growing

Each chart represents a grid operator or area

Texas (ERCOT)

West, excluding California

California (CAISO)

North-east

Florida (FRCC)

Texas (ERCOT)

West, excl. California

California (CAISO)

North-east

Florida (FRCC)

The Trump administration has sought to ease delays by fast-tracking environmental assessments and other permits. It has also invoked emergency powers to delay the planned retirement of older, typically coal-fired plants.

The president’s moves against renewable energy projects have been challenged in court by environmental groups, who warn that they undermine efforts to deploy some of the cheapest and quickest ways to add capacity.

“Our biggest concern is ending the attacks on solar and batteries . . . if you’re forfeiting the energy race to China, then you’re forfeiting the AI race to China,” said Jesse Lee, a senior adviser at Climate Power, an advocacy group.

“You can’t win that race if you’re trying to restrict wind, solar and batteries. There’s a five- to seven-year wait time for natural gas turbines right now. That’s just not an option.”

Replacing ageing kit is central to supporting grid expansion. Many poles, wires and transformers from the 1960s and 1970s remain in service, after two decades of underinvestment that was partly masked by efficiency gains.

On average, federal permitting for a new US transmission line takes about four years, according to the Department of Energy. State processes add further delays to grid build-out.

Last year, almost 900 miles of new high-voltage transmission lines were completed, according to lobby group Americans for a Clean Energy Grid. This is the most since 2020, but still far short of the 5,000 miles a year the group estimates is needed to support grid reliability and growth.

Sourcing equipment to strengthen the grid, connect new customers and build capacity has become another constraint.

Shortages of large electric transformers — devices that transfer electrical energy between circuits — are driving up prices and delaying projects.

Anthony Allard, US managing director at Hitachi, a major supplier of grid equipment, said transformer lead times were “three to four times” longer than in 2020.

Companies building natural gas plants face similar challenges. According to the International Energy Agency, most new US data centre demand will be met by gas over the next decade.

But since 2023, delivery times for large gas turbines have more than doubled to about four and a half years. As a result, building new gas capacity now costs about $2,400 per kilowatt hour — up 71 per cent in four years, according to energy research group Wood Mackenzie.

The flurry of activity by hyperscalers has caught the attention of regulators. In November, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation warned that data centre expansion was straining grid infrastructure and raising the risks of power outages during extreme weather events.

Jim Robb, Nerc’s chief executive, said the agency had been “sounding the alarm” for two to three years due to increased demand but that the data centre boom was like “nothing we’ve ever dealt with before”.

The scale of investment required to meet this rising demand is stoking fears of higher utility bills and spurring locals already concerned about water usage and the impact data centres could have on their health. The backlash has forced Amazon, Google and Microsoft to scrap plans for facilities this year in states including Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Consultancy ICF estimates residential power prices could rise 15 to 40 per cent over the next five years. Data centres are not the sole driver, but they are amplifying affordability concerns and clash with Trump’s pledge to halve electricity prices within a year of taking office.

Flexible solutions

Grid setbacks have led hyperscalers and model builders to seek alternative power solutions, including building capacity outside the traditional grid.

xAI operated its Colossus data centre cluster in Memphis, Tennessee, with dozens of gas turbines for much of the past year without environmental permits, according to the Southern Environmental Law Center. The group has accused Elon Musk’s company of being the state’s largest “industrial source” of nitrogen oxide pollution and misleading residents over the number of turbines in operation at the site.The company received a permit in July that enabled it to run 15 turbines as a form of back-up generation, though SELC said that it has observed as many as 35 turbines on site. xAI did not respond to a request for comment but has previously said that a number will go offline.

Data centre

Gas turbines

Data centre

Gas turbines

Data centre

Gas turbines

Data centre

Gas turbines

Several other data centre developers are turning to onsite gas generation — where power does not come from the grid — to meet their deadlines. OpenAI’s Stargate facility in Abilene, Texas, is set to include 10 natural gas turbines with a capacity of 361MW. Meanwhile, planning documents outline Meta’s goal to add 200MW of this so-called behind-the-meter generation to its Prometheus cluster in Ohio.

Analysts expect that this type of activity will persist while the network is unable to meet data centre demand. There is also a drive to reopen some nuclear plants that were mothballed in the past five years. Following a deal with Microsoft, Constellation is planning to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania from 2027 to address capacity shortages.

Many utility companies are pinning their short-term hopes on “demand response” solutions that require companies to curtail activity at peak times.

AI model builders typically run data centres at full capacity during “training runs” — where they feed LLMs with vast amounts of data to improve accuracy. These rises in activity can clash with consumption from other customers — including households — during peak usage, increasing the risk of blackouts.

Companies including OpenAI have also asked US regulators to speed up interconnection requests for flexible data centres, arguing that it will help “reduce costs” for all users.

“We have to get smarter about using unused capacity on the grid,” said Daniel Eggers, executive vice-president at Constellation, a power company that supplies 2mn US homes and businesses.

Researchers at Duke University said earlier this year that if data centre operators could restrict their consumption 0.25 per cent of the time, the grid could accommodate about 76GW of additional demand. They cautioned that this would not replace the need to build new capacity.

Brandon Oyer, head of energy and water for the Americas at Amazon Web Services, said the company could tolerate some curtailment on a temporary basis, but did not consider it a “smart investment” to do so for a prolonged period of time. “Some customers might be able to tolerate that. Some customers might not. It’s going to be a very nuanced decision.”

A white knuckle ride

The concern for hyperscalers is that this patchwork of measures will not be enough to power data centres coming online over the next few years.

In this scenario, a raft of projects will no longer be viable because they cannot meet contractual commitments. Others will have to simply wait for upgrades to the electricity grid and the construction of new generation capacity to be completed.

In a race between global superpowers, AI could be slowed down by decades old grid infrastructure and a failure to provide adequate capacity.

For some, the power crunch eases concerns of overbuild. For tech companies and the Trump administration, it may undermine billions of dollars in investment.

“We may not get all this done in the timeframe that hyperscalers would like . . . and they won’t be able to interconnect until we’ve got the resources to meet them,” said Nerc’s Robb. “It’s going to be a white knuckle ride.”

Additional work by Sam Joiner, Jana Tauschinski and Martha Muir.

Figures for the current and projected data centre capacity from S&P Global Energy and 451 Research. These totals exclude cryptocurrency mining and enterprise-owned data centres, defined as facilities owned by organisations whose business is not primarily focused on providing data centre leasing services. To estimate data centres’ peak impact, an 80 per cent capacity utilisation during the peak period is assumed.

Data on the power capacity of individual data centres is from Epoch AI’s frontier data centre database that uses publicly available data, satellite images and permitting documents to track compute, power use and construction timelines.

Data on locations of individual operating and planned data centres from DC Byte.

All satellite images from Planet.