Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There are many rules that govern sumo wrestling, the Japanese sport that operates on the principle of pushing another man down or out of a circular clay ring. But what epitomises wrestlers, in Japan at least, is their distinctive topknot.

The mage topknots originated around the 17th century, favoured by the Samurai warrior class. When the Edo period ended in the mid-19th century, however, the warrior class was abolished along with the last shogunate’s government. In the Meiji era the new government, eager to modernise its society, passed an 1871 law that allowed people to choose their own hairstyle. It accelerated the trend among men to do away with their mage and wear their hair short. Yet despite the national phenomenon, the sumo wrestlers still preserved the mage.

The number of professional sumo wrestlers in Japan peaked at 943 in 1994; today, the number is closer to 600, with 2024 seeing the lowest number of hopefuls taking part in the Japan Sumo Association’s test for recruits. Newcomers are put off by the strict lifetime commitment required: wrestlers in training must live, eat, sleep and train in beya, or stables, with their peers, and are not paid a salary until they begin to rank in tournaments. The audience, however, is growing: last year was the first time in nearly 30 years that tickets for all 15 days at each of the six Sumo Grand Tournaments sold out, fuelled by domestic interest as well as record numbers of international tourists, with more than 36.8mn visiting Japan in 2024. In October, London’s Royal Albert Hall hosted a five-day sold-out tournament. In June 2026, sumo will travel to Paris for the first time in more than three decades.

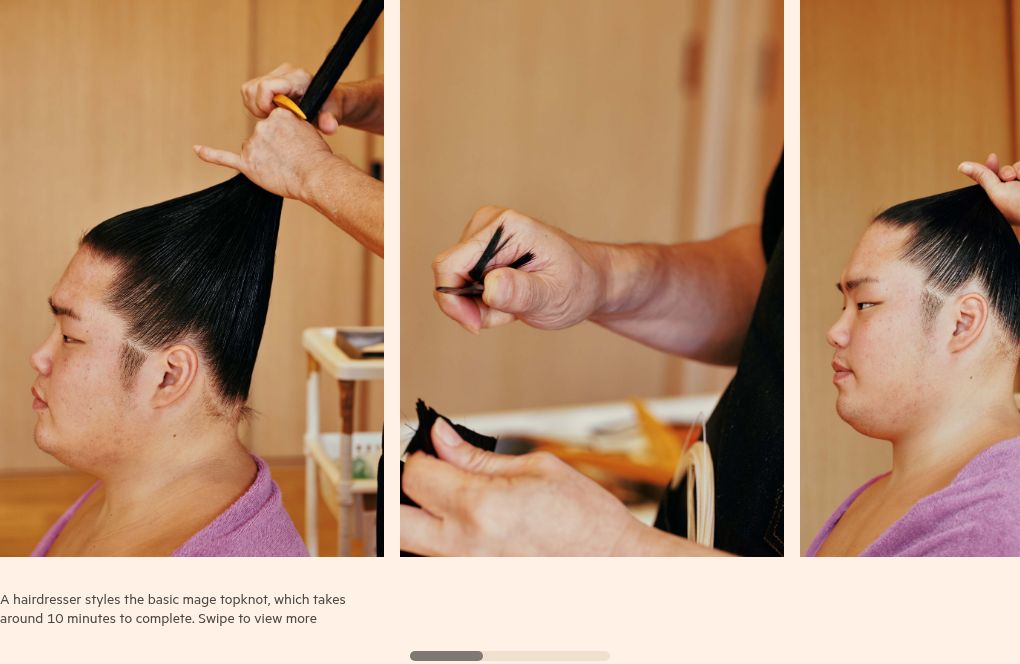

Guardians of a hairstyle that has remained unchanged for centuries, the wrestlers’ hairdressers (known as tokoyama) will be travelling with them. The mage speaks to sumo’s dignity, rooted in rituals that pray for bountiful harvests. Today there are two hairstyles: the basic topknot, resembling a ponytail swept forward from the back of the head, and the Ōichō topknot, which features hair styled into a ginkgo-leaf-shaped fan, reserved for top-tier wrestlers.

Of the 46 tokoyama currently affiliated with the Japan Sumo Association, Takeo Masuyama ranks among the top five, with 43 years of experience. Now aged 58, he trades under the professional moniker Tokotake, adapted from his given name Takeo. Tokotake operates out of the Kokonoe beya in Tokyo, one of 45 in Japan, with 20 wrestlers who require hair styling every day after their morning training session, which starts at 6am and finishes around 10am.

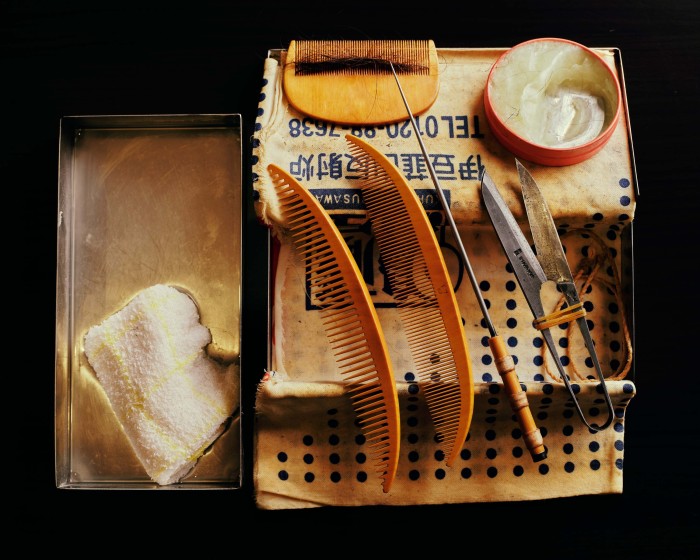

The process begins by rubbing the wrestler’s hair between both hands to untangle it. “Each wrestler’s hair is different – some coarse, some naturally curly. Rubbing the strands evens out the texture to ensure the mage can be neatly tied,” Tokotake says. Applying four different boxwood combs, he moves his hands rhythmically back and forth using camellia-blended oil that stiffens into a paste, preventing the wrestlers’ hair, which is about 40cm to 45cm in length, from slipping around in training. Keeping one hand on the gathered hair, Tokotake takes a motoyui cord made of washi paper in the other, and bundles the hair to form a mage. He can’t afford to be leisurely: taking too long tires the wrestlers who sit on the floor rather than chairs at a height that is more convenient for the technician. No one except the wrestlers themselves and the tokoyama can touch their hair – a reminder that sumo wrestling is a sacred act.

There are many factors at play when attending to the topknot. “Pulling the hair too tight causes headaches, while tying it too loosely means it easily comes undone,” says Tokotake. “Wrestlers sleep with their topknots, so they must be firmly teased into position so that they do not go loose until the following day.” Another concern is the positioning. “The topknot mustn’t be too far back on the head, or it won’t be visible from the front. Yet if it’s too far forward, it looks awkward.”

A basic mage style takes less than 10 minutes for Tokotake to complete. The elaborate Ōichō topknot is more time-consuming. An iron rod is inserted into the gathered hair to create a fan effect. “The art of the arrangement is to spread the hair so it’s all tightly packed together, ensuring no gaps appear between strands,” he explains.

It was Tokotake’s father who, after watching sumo on television, decided his dexterous 15-year-old son should become a tokoyama. He applied through the Japan Sumo Association to Kokonoe beya where he now belongs. “I knew nothing about sumo and had no interest in it, but I followed my father’s decision,” he says. He was not a natural. “In the beginning, I was clumsy, found it tedious and thought of quitting many times. Still, after several years, I grasped the knack and then it became rewarding.”

Since then, he has been arranging wrestlers’ hair every day and accompanying them to tournaments. “Each wrestler has their own aesthetics and is particular about certain things.”

He believes that hair affects the outcome of matches. “When a wrestler is on a losing streak, I change the Ōichō topknot slightly. So when the wrestler wins, I feel like the hairstyle played a part in the victory – it’s truly an honour.” For the sumo wrestlers themselves, hairstyles can influence their mental state. “As the hair gradually ties into Ōichō, I feel motivated, competitive, thinking, ‘Right, time for the bout,’” says the wrestler Chiyosakae. Tying the knots is the fruit of an ongoing dialogue between wrestler and tokoyama, building a mutual trust.

What brings Tokotake the greatest fulfilment? “When the wrestler whose hair I arranged wins a grand tournament – which is not that often,” Tokotake says. “One memorable match was when [the now-retired champion] wrestler Chiyotaikai won the grand tournament. I have done his hair since he joined the stable as a fledgling wrestler and watched him advance, so seeing him win the title was pure joy.”