Cruising along a raised highway in eastern China, Marcus Hafkemeyer takes his hands off the wheel and smiles as the car indicates, brakes softly and changes lanes itself. “I’m very proud,” he says.

The German engineer is demonstrating Volkswagen’s rapid progress in offering assisted driving functionality to customers in China. Later, in an underground car park, the vehicle remembers its designated space and reverses effortlessly into the spot.

The technology, a forerunner to completely driverless cars, has taken the German company about 18 months to develop, test and now commercially deploy — all in China. It is the fruit of a 700-person research and development team comprised mostly of Chinese software engineers with masters or PhDs and more than five years’ experience.

Asked how long it would have taken to deliver something similar back home, Hafkemeyer, who worked with Audi, Chinese state-owned auto group BAIC and tech giant Huawei before joining VW in 2022, sighs with exasperation. Typically, he says, the technology development cycle in Germany is a slog of around four to four-and-a-half years, where ideas are bogged down in endless internal debate and commercial negotiations with suppliers.

“This country has in the last 10 years moved from third gear to fifth gear and is going full speed,” he says. “I still hear in the news ‘the Chinese are coming with their cheap cars flooding the European market’. I’m telling you, come here, look at these ‘cheap cars’. They are full of technology. Their quality is so good.”

Volkswagen’s tech ambitions in the country were originally aimed at winning back Chinese customers lost to a clutch of local rivals, including BYD, which have been faster to embrace the EV transition. The strategy was dubbed “In China, for China”.

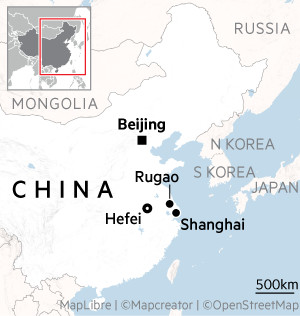

But now a stream of German engineers are travelling to the group’s R&D centre in Hefei, a city in Anhui province, gleaning what they can from their new colleagues.

For decades, China has been the world’s factory and companies have tapped into a low-cost labour force with few protections and cheap, dirty energy. The country’s scale — as a manufacturing base and as a consumer market — lured almost all the world’s biggest multinationals. But the underlying technology was retained by companies from the US and Europe.

Now China’s research and development prowess is allowing it to compete, and potentially beat, the west.

Whereas the biggest focus of US innovation has become potential moonshot technologies such as artificial general intelligence, for Beijing R&D largely focuses on addressing shortcomings in the real economy — part of Xi Jinping’s pursuit of technological self-sufficiency.

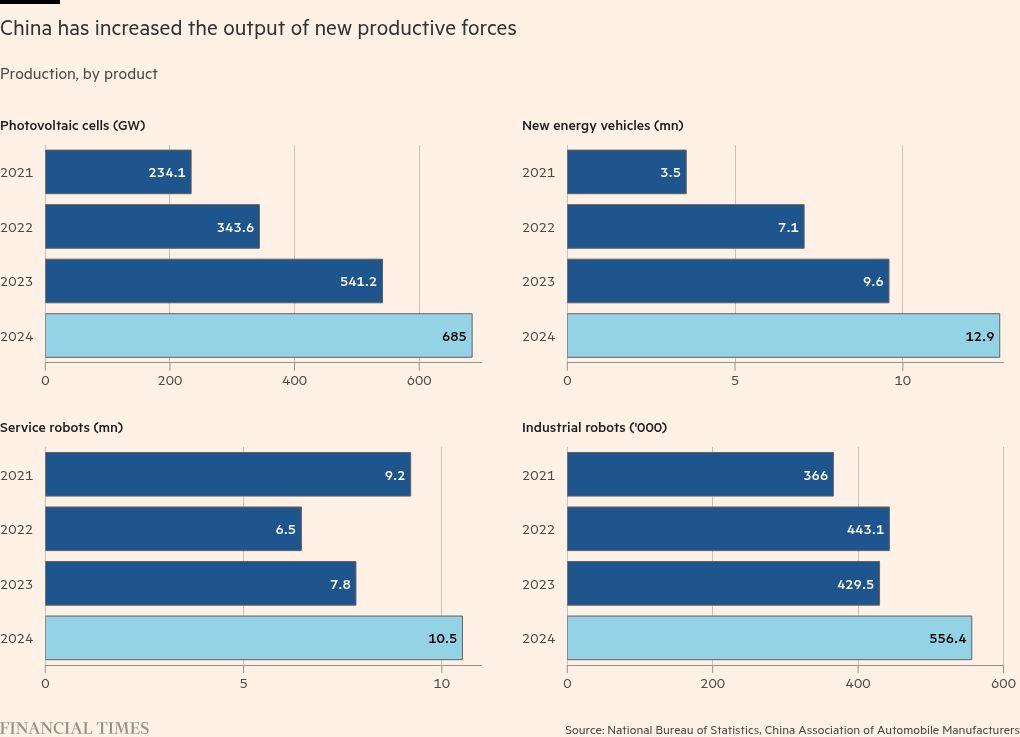

After years of state, corporate and academic efforts to alleviate basic vulnerabilities, China’s advances are now setting up the country to dominate future global supply chains for energy and transport.

Compounding inertia in the west are the sweeping cuts to US science funding made by Donald Trump since he returned to the White House, a move that threatens to undermine the innovation that has been central to the country’s economic strength for decades.

As China makes progress, government officials and business executives must decide whether to compete, collaborate or attempt to coexist with the country.

Dan Wang, China director at consultancy Eurasia Group, says China’s centralised political system and the Communist party’s command over the economy are giving it “the upper hand” over liberal democracies when it comes to new technologies that require long-term investments.

Beijing’s commitment to high-tech industries, including to the basic sciences underpinning them, appears to be “much higher than the US”, she says. This is almost certain to continue — even if it means one or two generations of Chinese people suffer as a result of the country’s fiscal resources being diverted from welfare.

“Focus is the key,” Wang says. “The Chinese government has a sense of urgency, they believe they don’t have a lot of time and in this competition with the US, China must win.”

In 1943, during a period of Japanese occupation, British sinologist Joseph Needham made the first of many trips to China from which he chronicled a rich history of the country outpacing the west. Chinese innovations included the invention of antimalarial drugs in the third century BC and, a few hundred years later, an algorithm for the extraction of square and cubic roots.

Travelling through China’s war-torn provinces, however, Needham encountered the nation’s academia on its knees. Ninety per cent of China’s more than 100 colleges and universities were damaged during the Japanese invasion; many were bombed or looted.

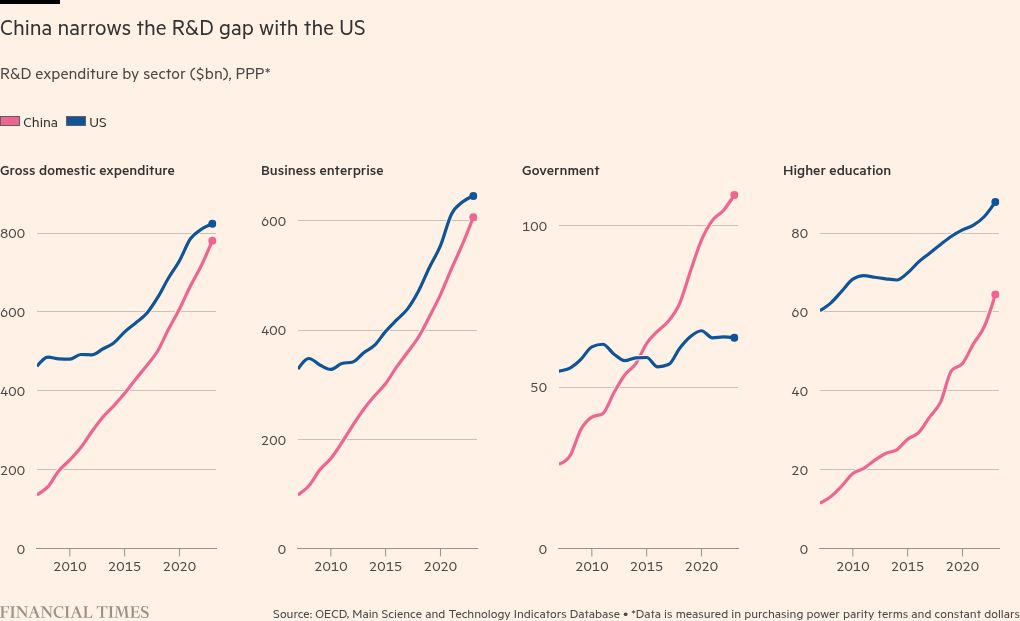

Eighty years later, Chinese research is utterly transformed. The country is close to overtaking the US in total expenditure on R&D, with China spending $781bn and the US $823bn in 2023, according to the OECD. It is a stark change from 2007 when China’s R&D spending of $136bn was less than one-third of the $462bn spent by the US.

The potential inflection point follows years of debate in the west over the wisdom of China’s state-led development model, with evidence of vast sums of state finances wasted through subsidies and corruption, and criticism over the quality of Chinese academic research and patents.

According to some experts, it is not just the scale of China’s R&D budget, but a shift in the nature of that spending that warrants scrutiny.

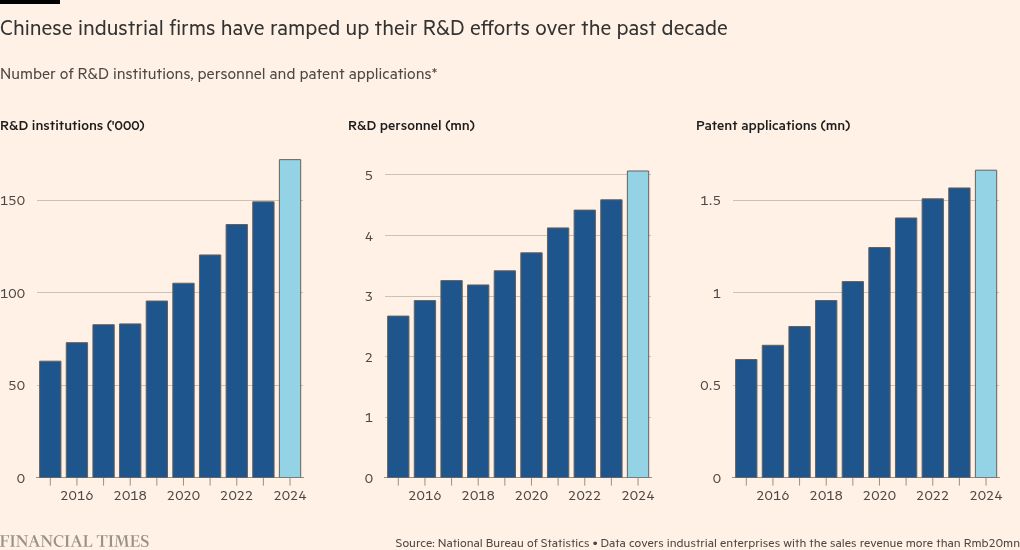

While government R&D spending in China has exceeded that of the US since 2015, Chinese companies have also rapidly increased their R&D efforts over the past decade, national statistics bureau data shows. The number of corporate R&D institutions has also nearly tripled to more than 150,000. And the number of corporate R&D personnel nearly doubled to 5mn.

China is also producing around 50,000 PhD graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (Stem) fields annually, compared to about 34,000 from US universities.

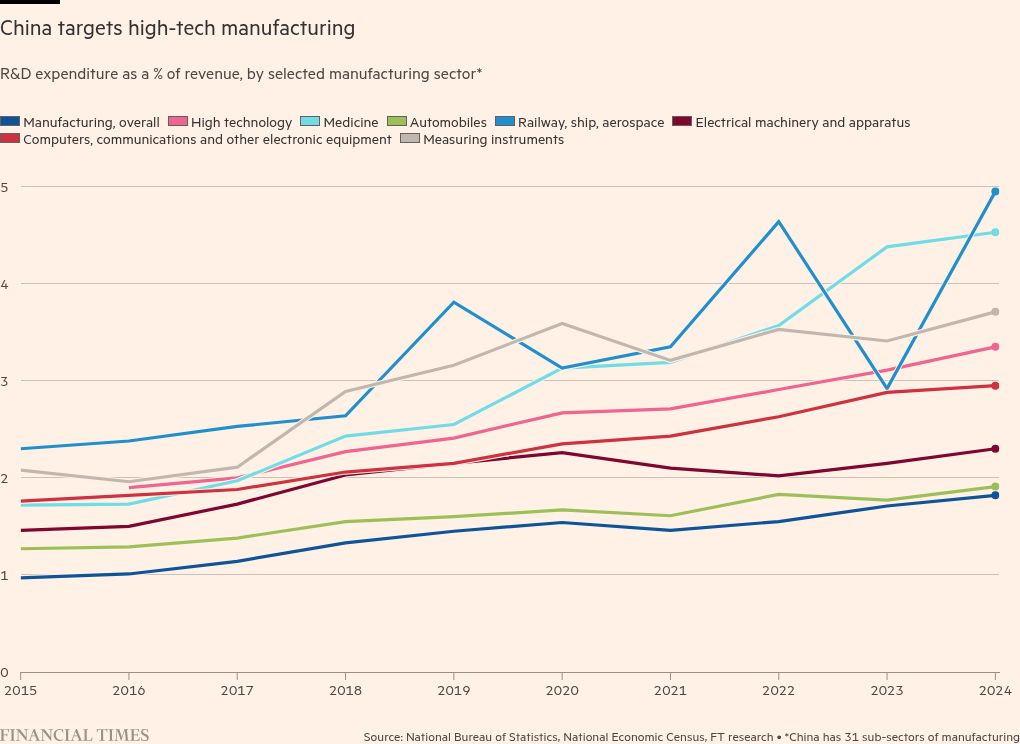

Lizzi Lee, a fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis, says that China’s R&D surge has been concentrated in applied areas tied to industrial transformation. This has included advanced materials, 5G, batteries, power equipment and other so-called “enabling” technologies that serve strategic goals.

“The focus has built deep advanced manufacturing ecosystems around scaling and integration into the real economy, rather than ‘blue sky’ science,” she says.

For Europe and the US, Lee adds, there needs to be a realisation of the challenge to compete with China “on China’s terms”.

“It isn’t just catching up on long-term spending, which is already close to impossible. It is competing with a system that fuses industrial policy, advanced supply chains and robust engineering and Stem pipelines into one machine.”

For years both foreign and local observers of China’s research efforts have been highly sceptical of the quality and value of Chinese academic research and claims of technological breakthroughs.

Following an explosion in the volume of Chinese patents — which has seen the country lead the world in filings since 2011 — China’s electronics industry association leader Dong Yunting estimated in 2019 that around 90 per cent of the country’s 7mn patents that year were “rubbish”, used only to secure project funding.

The reliability of China’s EV tech has also come under scrutiny. This was highlighted by the death in eastern China in March of three people in an accident involving a Xiaomi electric car with semi-autonomous capabilities.

Angela Huyue Zhang, a professor of law at the University of Southern California, says that admirers of Beijing’s state-led model “often ignore the fragility” that comes with centralised, tightly coupled governance, pointing to China’s mishandling of the Covid-19 pandemic and heavy-handed property reforms that have led the economy into a prolonged economic slowdown.

And yet many foreign companies are increasingly of the view that collaboration is the only path to survival.

At a sprawling industrial park on the edge of Rugao, north-west of Shanghai, Scania, a truckmaker, opened a €2bn factory in October. There, the Swedish company plans to integrate cutting-edge Chinese technology into its vehicles for its customers both in China and overseas.

Sonia Ederstål, the head of Scania’s China R&D division, says the environment for innovation in China is “completely different” to the west. She points to the truckmaker’s quest to introduce autonomous driving functionality as an example.

“We have been trying to do this in Sweden, in the US, everywhere,” she says. “Within one year [in China] we were able to integrate the software into our vehicle and make it run completely in that mode.”

Since 2018, Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen and Stellantis have formed technology partnerships with at least 38 Chinese companies and research institutes, covering software, hardware, batteries and connectivity, UBS data shows.

In Shanghai, long the country’s preferred hub for foreign companies, the number of foreign-owned R&D centres has increased to 631, as of September, from 441 in 2018. French automaker Renault does not even sell cars in China, but it is among those companies to have opened an R&D centre in Shanghai this year to learn from the local market.

Beijing also saw 58 new R&D centres established by foreign groups in the first 10 months of the year, expanding the total number of foreign R&D centres in the city to 279, according to local officials.

Many areas of Chinese R&D are at the sharp end of technological competition with the US, including artificial intelligence, robotics and quantum computing, bioscience and pharmaceuticals, aerospace and nuclear weapons.

However, the OECD data reveals that a central focus for China over the past 15 years has been basic engineering and materials.

China’s research advances across areas such as batteries, renewables and alternative fuels are edging the country closer to Xi’s aims of self-sufficiency by cutting a reliance on imported fossil fuels and tech across scores of heavy industries.

OECD analysts noted in a report that China “does not only lead in environment-related product manufacturing and exports, but increasingly also in the creation of relevant knowledge”.

For example, China now has 54 commercial-scale clean energy industrial projects either in operation or financed — this covers chemicals such as methanol and ammonia as well as metals like aluminium and steel. That is three times more than in the US, according to data from the Industrial Transition Accelerator, an international non-profit.

Faustine Delasalle, executive director of ITA, says that Chinese companies appear more willing to take the leap from R&D to longer-term commercial investments.

“There’s an acceleration in China that we’re not seeing in the rest of the world,” she says.

When the Chinese Communist party’s elite Central Committee met in late October to lay the groundwork for the country’s 15th five-year plan, they left little ambiguity about their intent.

“In the coming period, the technological revolution and great-power rivalry will increasingly intertwine, intensifying competition in new technologies and emerging sectors,” Ding Xuexiang, China’s vice-premier who is responsible for science and technology, wrote in a 454-page explanatory commentary.

Behind the scenes, however, officials are trying to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past where billions of dollars intended for technological gains were wasted. The litany of problems includes corruption among officials and the misallocation of funds by local governments and companies.

Beijing is trying to develop a new system for funnelling capital into strategic industries across the country, but with the central government keeping a tight grip.

Qiu Yong, vice-minister of science and technology, said in May that China’s approach to tech-sector financing was shifting “from fiscal thinking to financial thinking” — a pivot from emphasising the scale of funding to focusing on disciplined capital allocation.

Late last month, a $7.2bn fund for central government state-owned enterprises was launched to invest specifically in “strategic emerging industries” such as AI, aerospace, high-end equipment and quantum technology, as well as in energy, information and advanced manufacturing.

At the same time, Beijing is trying to force local governments to cut back spending on industrial expansion to curb the reckless fundraising and waste that has played a role in chronic overcapacity in the economy as well as fuelling corruption.

Tilly Zhang, a technology and industrial policy analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics, a Beijing consultancy, says China’s next stage of technological development will be funded differently from the past.

“Official statements have signalled a shift away from the decentralised model that relied heavily on local authorities, towards a more centralised system in which state-owned financial institutions play a bigger role,” she says.

Still, Wang of Eurasia believes that Chinese officials remain willing to accept investment waste as they cultivate new national champion companies in important strategic sectors.

“They know that creating a bubble in the beginning is key to create the kind of competition they need [to] then produce the best companies,” she says.

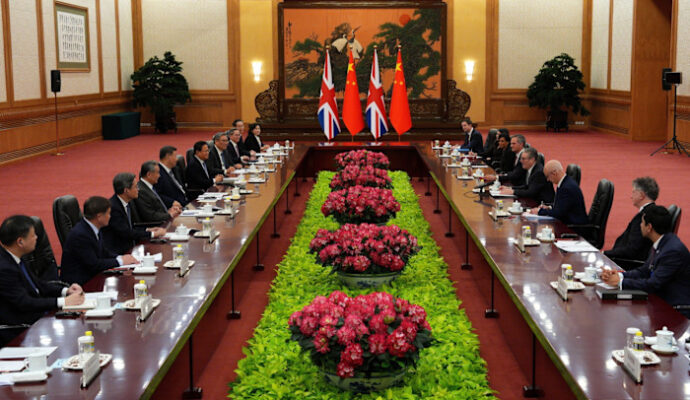

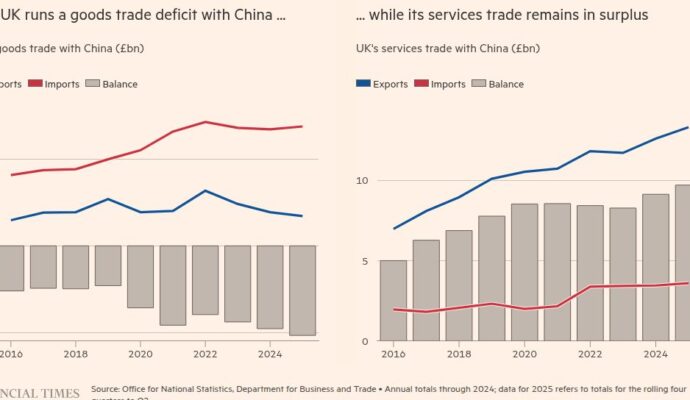

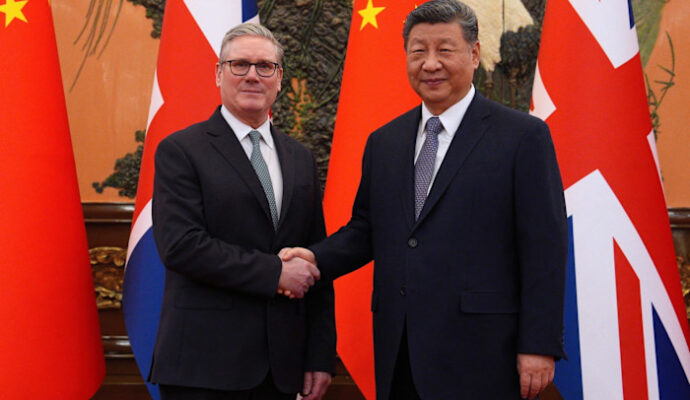

Earlier in November, Patrick Vallance, the UK’s science minister, landed in Beijing to sign a statement of co-operation with China on areas of health, climate, planetary sciences and agriculture. Absent were satellites, remote sensing technology and robotics, which an earlier agreement had included.

The latest UK-China statement highlighted the fine — perhaps impossible — balance countries must strike between benefiting from China’s rising intellectual and manufacturing might and exposure to myriad security and economic risks from over-dependence on China.

Ultimately, if “leading knowledge sits in China” then the worst thing countries can do is cut themselves off from being able to at least observe and learn from Chinese technology and innovation, says Mark Greeven, a Shenzhen-based professor of innovation and strategy at the International Institute for Management Development, a Swiss academic institute.

“If we don’t compete, don’t collaborate . . . then where is our knowledge going to come from? The onus is on other countries: what do you do to make yourself competitive?” he says.

Zhang, the US professor, says to win the tech race the US must “stay America”. That means leveraging its world-leading universities, scientific community and, most importantly, its democratic institutions with strong checks and balances, “rather than dismantling them”.

In Beijing, officials are considering what mistakes in bygone centuries lost China the scientific edge it once held over the west.

Vallance told the FT that during talks with his Chinese counterparts they brought up the name of Joseph Needham — the academic who revealed the country’s scientific prowess to the world.

“They are still asking the question: what is it that can make you not win?” he says.

Additional contributions from Cheng Leng, Haohsiang Ko, Eleanor Olcott, Gloria Li and Tina Hu