Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

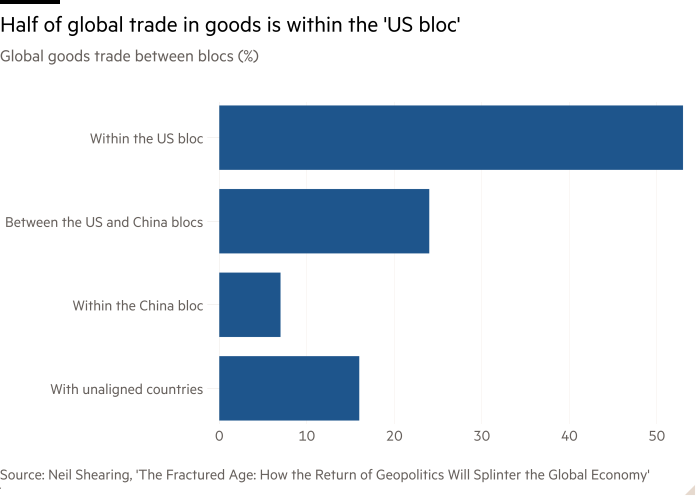

What lies ahead for the world economy? A plausible answer is that it has started to splinter. This is the argument of Neil Shearing, group chief economist at Capital Economics, in his thoughtful new book The Fractured Age. Fracturing, he notes, is not the same as “deglobalising”. Trade and other forms of globalisation might not shrink by much. This should be nothing like the collapse of the 1930s. But trade with rivals will shrink and trade with friends will rise. In particular, he suggests, the world will divide between a US-centred bloc and a China-centred one, with a number of unaligned countries stuck in between, trying to do their best.

Large parts of the US political elite already see China’s rise as the challenge of the age. Indeed, this seems to be almost the only point on which both parties mostly agree. Xi Jinping also drew a parallel between modern-day US “hegemony” and the “arrogant fascist forces” of 80 years ago, before a summit with Vladimir Putin last May. This is fighting talk.

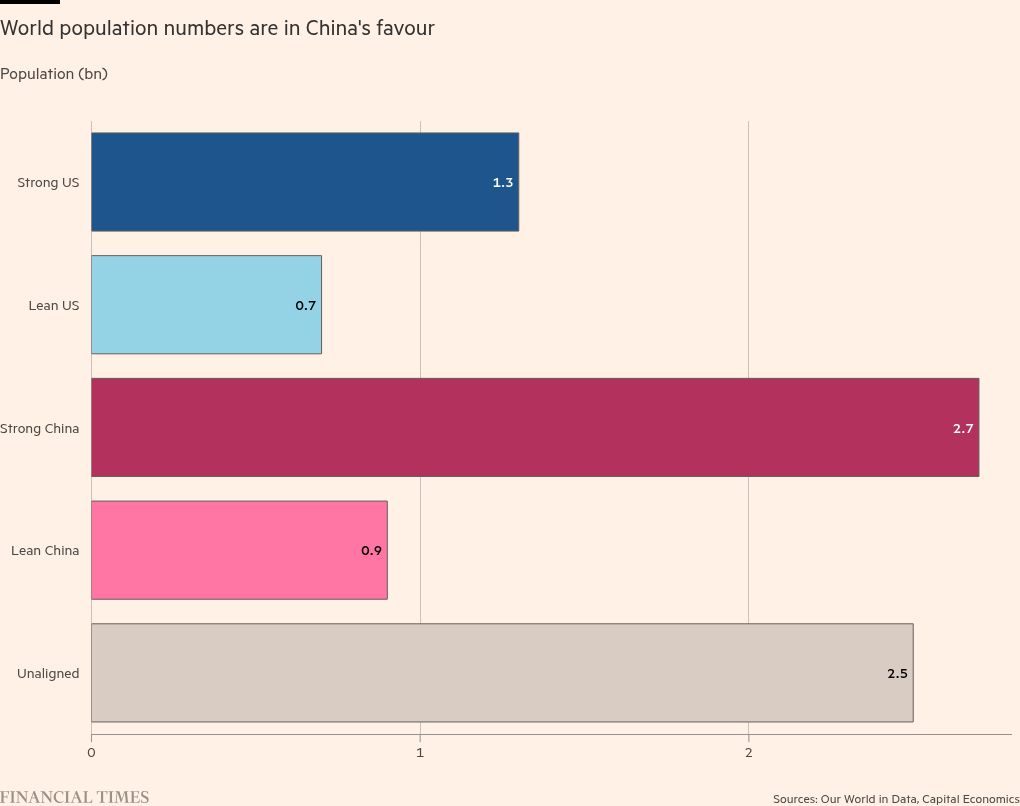

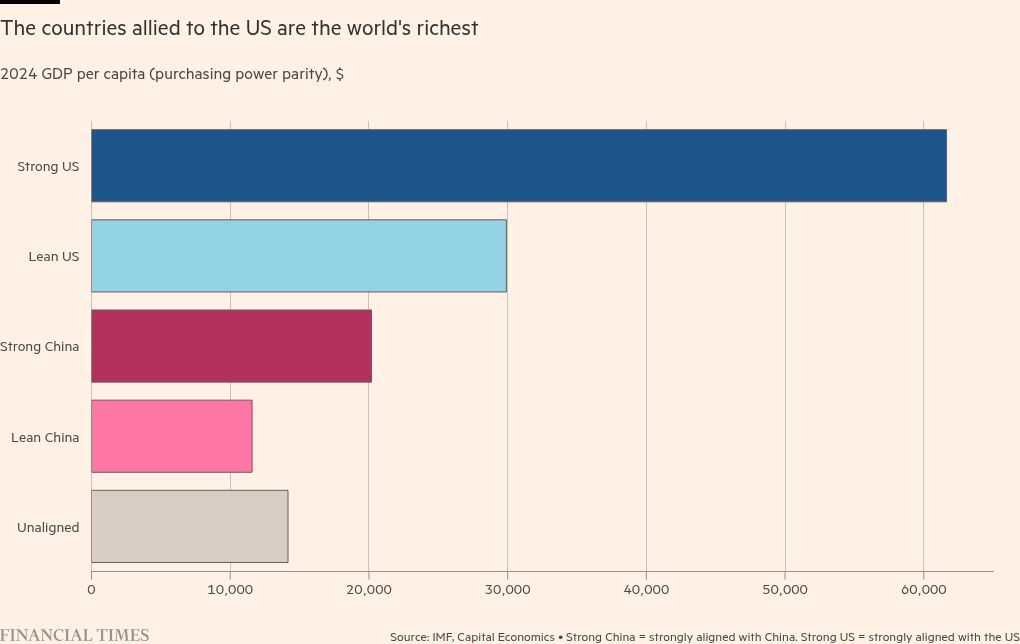

Shearing also argues that the US would come out ahead from such a fracturing of the world economy. The main justification is that America’s allies are more economically powerful than China’s because they include almost all advanced countries. Meanwhile, Russia is China’s only significant ally. At market prices, the US bloc’s share of world GDP is 68 per cent, against the China bloc’s 26 per cent. Even at purchasing power parity, the US bloc’s share is 50 per cent, against the China bloc’s 32 per cent.

A controversial point Shearing makes is that while many countries will wish to remain open to both sides, most will be forced to choose. In the end, the most economically potent countries in the world will stay closer to the US, because they depend on its security umbrella, its markets and its currency, or because, in the last resort, they distrust China more.

The US bloc is also more economically diverse and controls more fundamental technologies, notably in information technology. China has, as it has recently shown, created a powerful position in critical minerals and rare earths. But these can be replaced in the medium to long run. Moreover, the currencies and financial markets of the US and allies are globally irreplaceable. China does not even want to replace them, because it is highly averse to the sort of free-market economy that open capital markets would create.

Moreover, Shearing argues, China would also lose more than the US from a fractured world economy. One reason is that it has a structural current account surplus. The only countries where these funds can be safely invested are the US and its allies. The alternative is to lend vastly to developing countries, which may be unable to service their debts.

Finally. China’s economic growth has already slowed and is likely to slow still more. Shearing even argues, provocatively, that its growth rate might slow to 2 per cent, much the same as that of the US, partly because of this ongoing fracturing. Not least, none of the world’s big markets will tolerate the flood of Chinese exports that its industrial policies threaten. If this is right, China’s economy may never come to be decisively bigger than that of the US, let alone the US bloc as a whole.

The argument that the world (and so the world economy) is in the process of fracturing is correct. Shearing is also right that the old multilateralism is dying. But he is very likely to prove too bullish on the future of the “US bloc” and too bearish on China’s economic prospects.

One reason for the former view is that the US is mounting a suicidal assault on its principal assets. Among these was indeed its reliability as an ally, indeed as any sort of partner. Donald Trump’s behaviour towards Brazil, Canada, India and Ukraine, to name just four, has destroyed his country’s reputation for trustworthiness. Other assets under assault include the rule of law, support for science and its great universities, and openness to immigrants. Yes, many countries will continue to rely on the US. But if Trump’s fickle approach to the world is not repudiated, the “US bloc” may wither away. After all, Capital Economics itself has moved India into the “unaligned” camp from “leans US”.

Another reason is that it is an error to write China off. Two per cent growth is unlikely in an economy whose GDP per head (at purchasing power parity) is about 30 per cent of US levels. This is particularly true for China, given its extraordinary human assets. I agree that the current regime has adopted mistaken policies. But, as Deng Xiaoping showed, even destructive policies can be changed. My bet is that they will be. China will not accept poor economic performance indefinitely.

The big question, then, is which of the two would-be hegemons will abandon their current follies sooner.

Yet these counter-arguments do not alter Shearing’s forecast of fragmentation. They merely change the probable loser. They also do not change the obvious reality that a fragmenting world is likely to be a dangerous one. Graham Allison and James Winnefeld write in Foreign Affairs that “The past eight decades have been the longest period without a war between great powers since the Roman Empire.” Will this last if the world’s dominant powers believe they are playing a zero-sum or even negative-sum game?

Even without such calamities, a fracturing world will be harder for everybody to manage. The absence of the US from recent talks on climate is a salient example. We can debate whether China or the US will do relatively better in such a world. But the likelihood is that everybody will do worse in absolute terms.