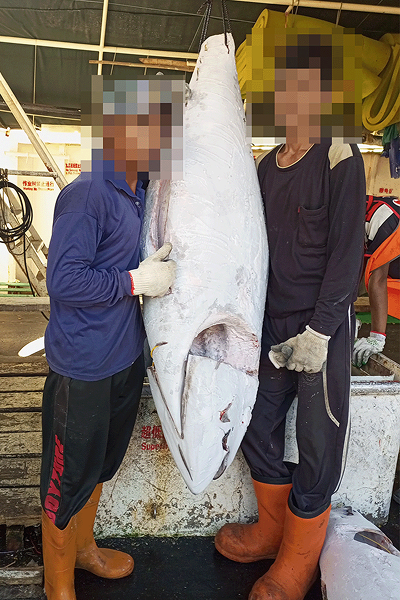

Deby Putra Bunanda can no longer walk more than a few steps or speak easily after spending seven months catching tuna in a fishery supplying cans for retailers around the world, including the US and Australia.

A bout of malaria and delayed medical treatment aboard a Taiwanese vessel in the Western Pacific in 2022-23 led to a close encounter with death and partial paralysis, he says.

Two years on, Bunanda relies on his wife, Erna Wati, for almost everything. “Before, I was healthy, I was bulky, and I could work freely. Now all I can do is lay around. I cannot do anything.”

The Indonesian fisherman — who also describes having his ID taken, being deceived over wages and having to repay a debt bond — says he endured gruelling hours in dangerous conditions off the coast of Papua New Guinea.

“They work around the clock with little rest,” says Wati, who is in contact with the wives of other Indonesian fishermen. “They don’t have any holidays. They are not given time to even go on land.”

The world’s biggest tuna fleets — from China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and Spain — dominate global tuna catches, operating vast numbers of vessels that roam the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans.

Labouring through blistering heat and violent storms, migrant crews from Indonesia, the Philippines and African nations form the backbone of the industry. But many endure brutal, dehumanising conditions similar to Bunanda, trapped at sea for months or even years, their rights routinely ignored.

Their experiences frequently meet the International Labour Organization’s definition of forced labour — work done under threat or coercion — a form of modern slavery that has become widespread across global fisheries.

An estimated 128,000 fishermen are trapped in such conditions, according to the ILO, with tuna fleets among the worst offenders.

Some 42 per cent of all recorded human rights abuses between 2000 and 2020 occurred on tuna vessels, according to research by the University of British Columbia and the NGO Ecotrust Canada, based on the world’s largest repository of fishery offences.

“You have no insight into the workplace . . . in stark contrast to every other supply chain I’ve ever worked on,” says Gill.

Alongside Bunanda’s experience, workers describe violations in two Western Pacific fisheries supplying British retailers with yellowfin, usually destined for fresh or frozen products.

Chinese vessels go on extended voyages breaching labour standards

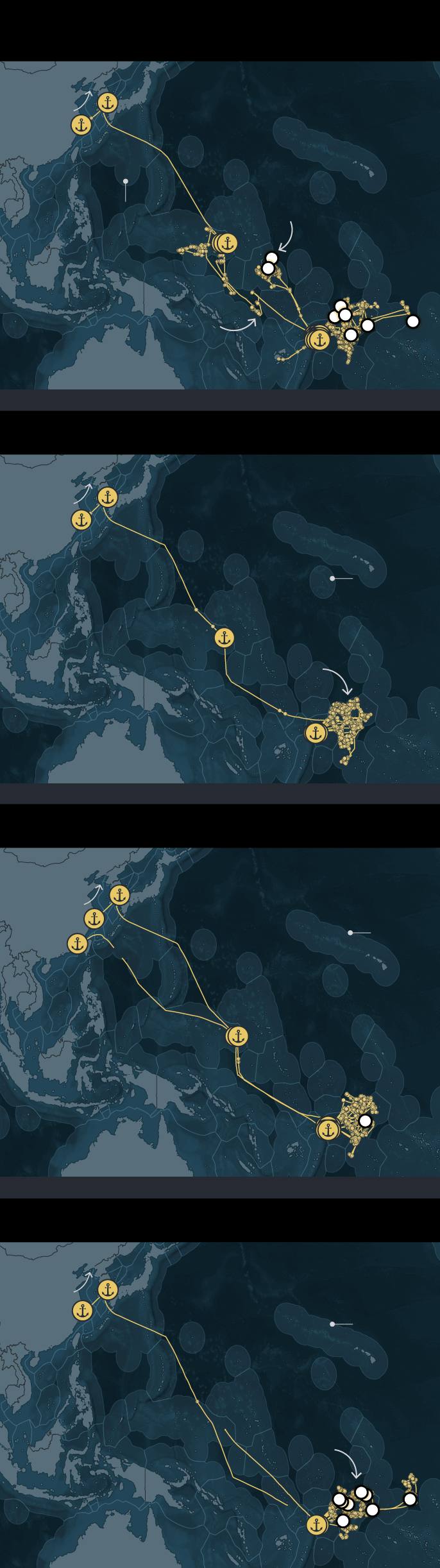

Graphic: A series of maps show the movements of four Chinese longline vessels — Huan Nan Yu 739, 716, 719, and 723 — operating in the Pacific Ocean between 2022 and 2025. Routes extend from ports in Busan and Zhoushan to fishing grounds near Micronesia, Samoa, and Fiji. Points indicate fishing events, transshipments and port stops, including repeated visits to Apia, Samoa. The maps highlight voyages lasting up to nearly four years.

While abuses in distant-water fleets from China, Taiwan and South Korea have been documented, this is the first time allegations have been directly linked to products on sale in British supermarkets.

“This tuna has no business on UK shelves,” says Zacari Edwards, co-ordinator of the Seafood Working Group, a coalition of organisations pushing for greater protection for fishermen, and GLJ’s senior seafood campaign coordinator.

Slavery at sea

In the dark of night, to the loud hum of the mainline reel, Indonesian fishermen catching tuna in a fishery used by major UK supermarkets can be seen hauling in branch lines and coiling them into drums, salt spray settling on their skin.

Video footage obtained by the FT lays bare the tough lives these workers lead.

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 video.

Unlike purse seine vessels such as Bunanda’s, which catch smaller tuna for canning using large nets, crews on these longliners target larger, high-end tuna and head out on voyages that can span years.

Crews rise before dawn and work late into the night, feeding out, baiting and hauling in lines that stretch for kilometres. Life on board is shaped by excessive hours, isolation and fatigue.

Accidents, sickness and poor medical care mean some fishermen never make it home, while others return to discover their family circumstances have changed.

“When they come back they find their father’s dead and all sorts of things,” says Fiji-based fisheries scientist Patricia Kailola, who surveys Pacific fishermen. One worker found his wife had married again during his long absence and took his own life, she adds.

It is in these isolated conditions, away from support networks, that exploitation thrives.

Testimony and paperwork from Indonesians across five Chinese vessels in two fisheries serving the UK describe patterns of abuse.

Crew working near the Cook Islands and Micronesia between 2018 and 2024 talk of violence, working excessive overtime, including when sick or injured, poor medical attention, having their ID documents taken and wages withheld — all ILO indicators of forced labour. One alleges he was threatened with a knife.

“He beat my body. He beat my legs. He beat me often,” says one worker about his captain.

“All of us were frequently slapped on Hong Yang 88 when we were new,” says another.

A crewmember on sister vessel Hua Nan Yu 739, says fishermen worked “non-stop”, only resting for two hours. “What we had to eat was spoiled rice, fish and some other disgusting steamed food,” he says, describing the desalinated, rust-coloured seawater they were given to drink as “poison”.

Signs of exploitation in their paperwork suggest workers were trapped in contracts by debts or the threat of having to pay compensation if they left.

Contracts and payslips contain forced labour red flags

There are also concerning patterns of behaviour in a third longline fishery serving the UK. Ship tracking data shows South Korean vessels spending excessive hours fishing while operating there and extended periods of time at sea without visiting port — both signs of forced labour. Voyage lengths lasting longer than a year, with port visits fewer than every six months, are widely regarded as red flags.

Francisco Blaha, a former fisherman turned independent adviser based in the Western Pacific, says that although levels of non-compliance “are very similar between China, Korea and Taiwan”, his own analysis suggests South Korea could be the worst offender. The Korean authorities and the company that owns the vessels said they are now taking steps to improve conditions for workers.

Waitrose and Sainsbury’s also said they are reviewing conditions on the Korean fleets along with a joint supplier and have a plan to address them.

South Korean vessels can remain at sea for years with few port visits

Graphic: A series of maps show the fishing routes of four South Korean longline vessels — Dongwon 201, Dongwon 205, Dongwon 203 and Dongwon 208 — in the Western Pacific Ocean. Each map traces voyages from Busan, South Korea, to fishing areas near Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Fiji between 2023 and 2025. Points mark fishing events and brief port or transshipment stops, illustrating voyages of up to nearly three years.

But slavery indicators are not confined to these Pacific supply chains, or just tuna.

A database of evidence collected by the UK-based Environmental Justice Foundation shows how abuses — especially across Chinese distant-water vessels — have become industrial in scale, says Steve Trent, the organisation’s CEO and founder.

“It’s not one single vessel, it’s not one single company — it is quite clearly systemic,” Trent says. “It’s every geography, every jurisdiction, every company. Pretty much every vessel that we’ve documented has got a mixture of abuses.”

EJF footage from the wider Chinese fleet shows fishermen being threatened, beaten and abused. Senior Chinese crew can also be seen carrying knives and firing guns.

Four Indonesian fishermen working in the Chinese tuna fleet and one on a Taiwanese vessel between 2016 and 2025 told the FT of similar experiences. Two say they remain traumatised after witnessing crewmates die from beriberi, a disease caused by vitamin deficiencies, which they blame on expired food and medical negligence. One worker on a Chinese vessel says he fished alongside people from North Korea, in potential violation of UN sanctions, which prohibit states issuing work authorisations to North Korean nationals.

“You’re almost compelled to ask the question, is this by design or by default?” asks Trent of the conditions. “I’m not sure that I would go as far as to say that there is a diktat from Beijing saying go out and do these things, but I do think there’s knowledge about the abuses and an unwillingness to address them.”

China’s ministry of foreign affairs rejects the claims, and says it is “a responsible fishing country” that has always carried out offshore fishing “in accordance with laws and regulations”.

Profit squeeze

Tuna is among the world’s most valuable fish, with demand rising alongside the push for protein-rich diets. Analysts valued the global market at $43bn-$46bn in 2024.

About 30 large companies control nearly half of this catch, according to Global Fishing Watch data analysed by financial think-tank Planet Tracker.

But as coastal fish stocks dwindle, these fleets are venturing farther out to sea and for longer, putting crews at greater risk.

Squeezed by low retail prices and rising costs, some fleet operators have turned to lower-paid migrant workers to save money. Experts say they often cut corners on safety, withhold pay, or break labour laws. Almost all of the big tuna fleets now rely on government subsidies and cheap labour to save money.

“If you want to point fingers, the fingers have to be pointed at the longline distant water fishing nations,” says fisheries adviser Blaha.

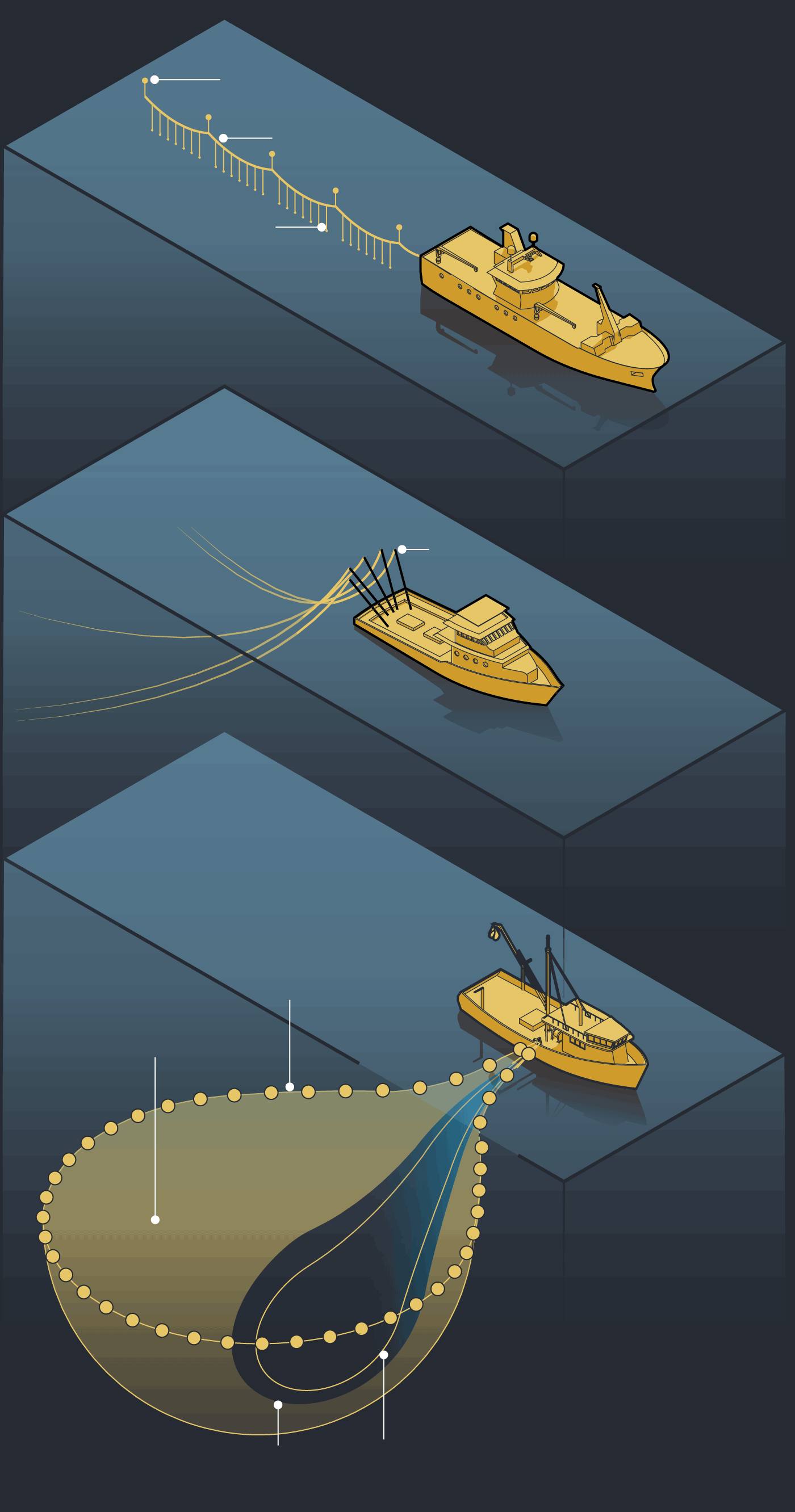

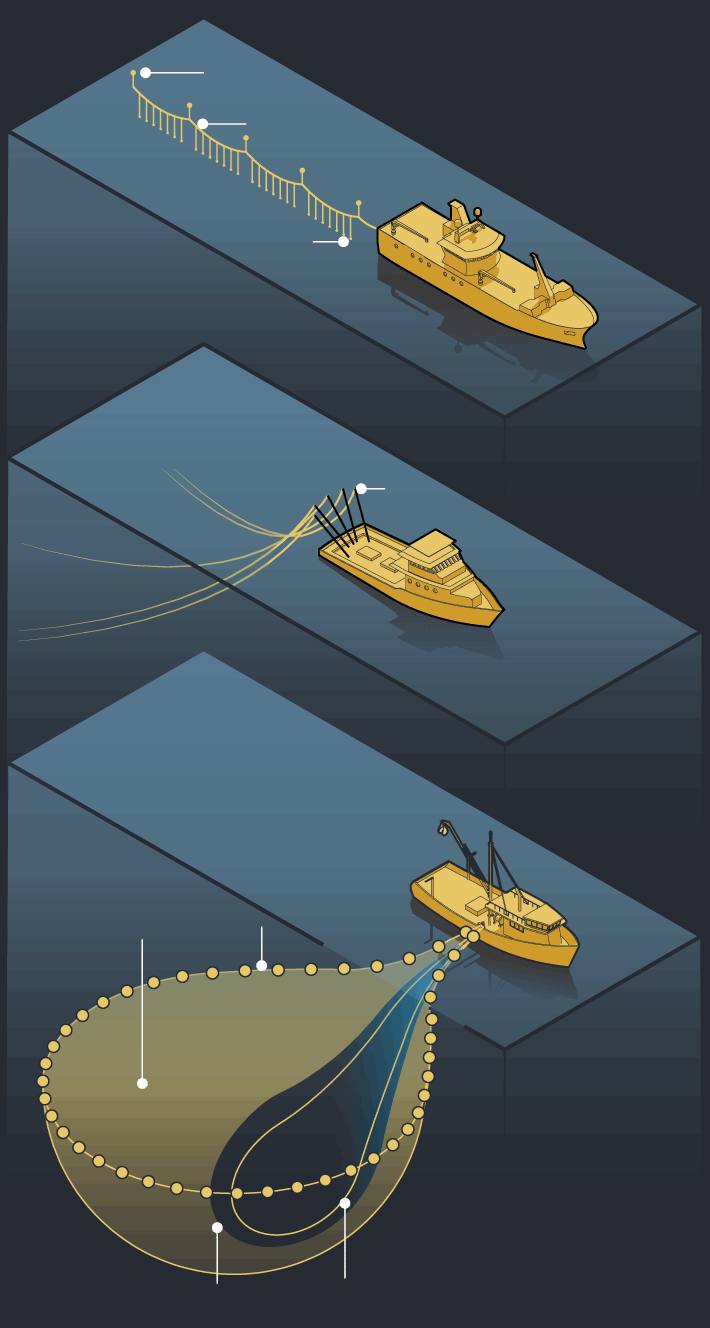

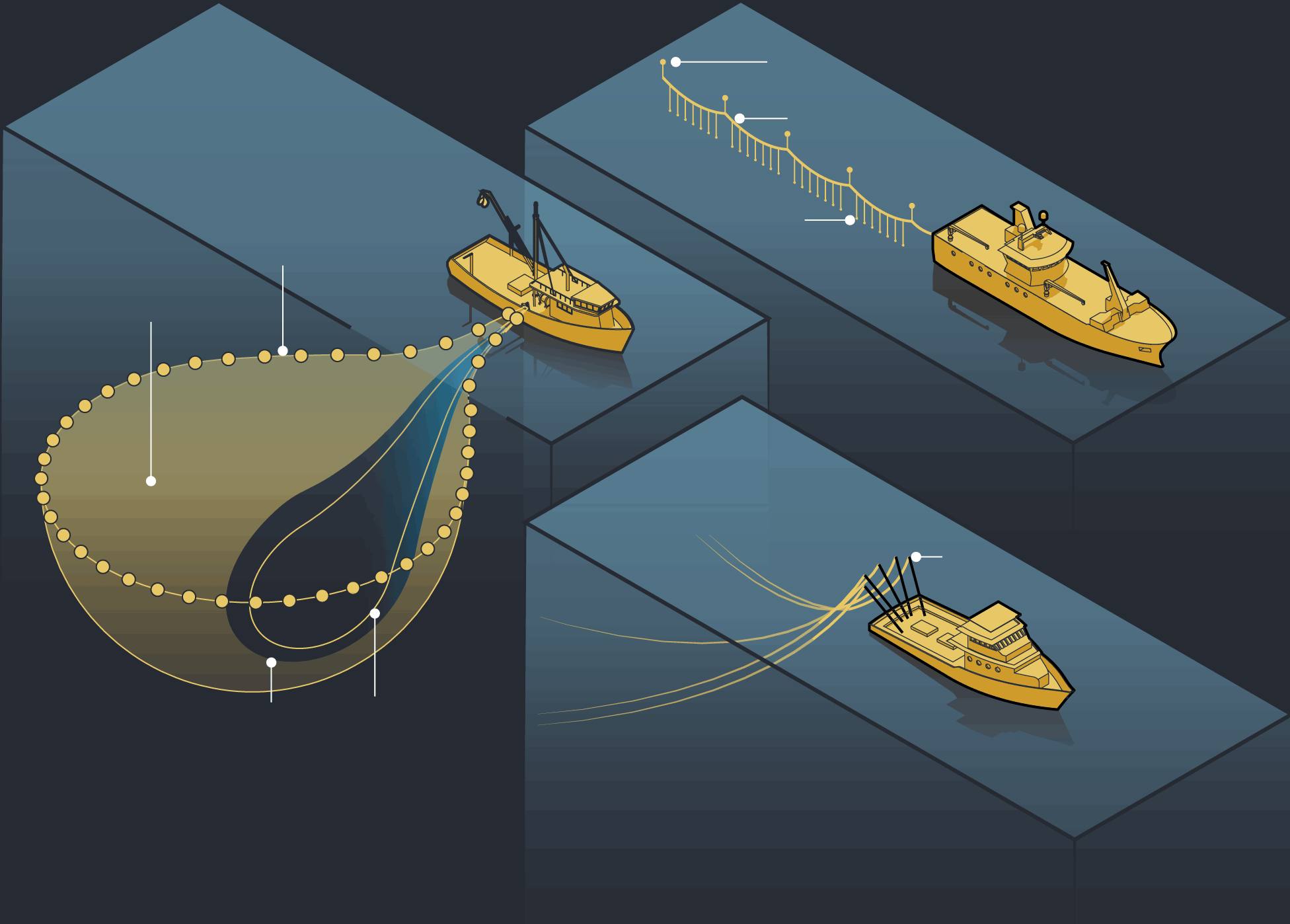

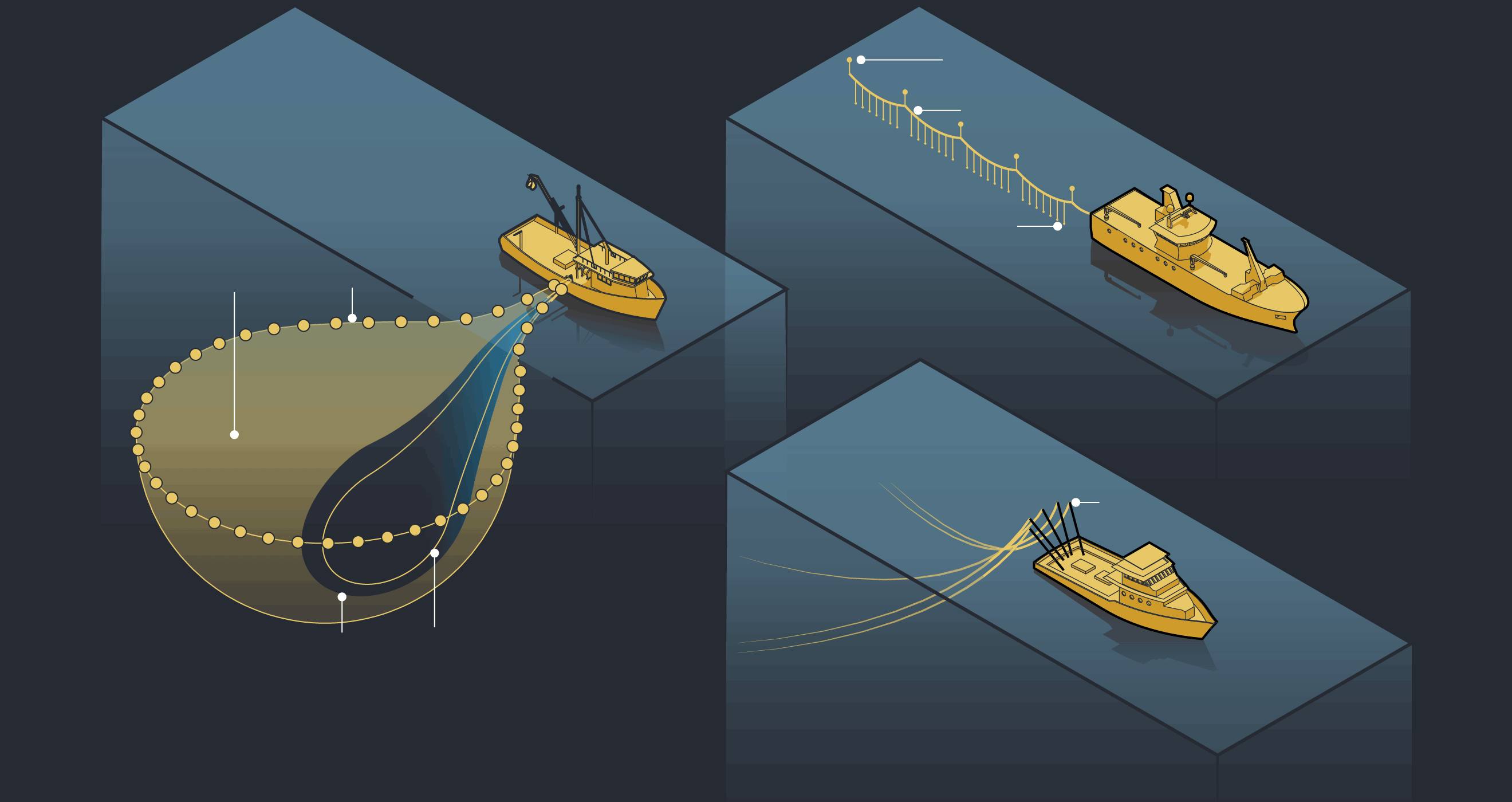

Longline methods have the highest forced labour risk

Graphic: Infographic comparing tuna fishing methods: purse seining with a large net encircling surface-dwelling fish; longlining with a mainline, floats and hooked branchlines for deeper-swimming tuna; and one-by-one pole-and-line fishing, shown as the most sustainable method

But while different fishing methods bring varying risks of forced labour, the current economics of industrialised fishing means they all face the same upstream pressures from the push for “cheap fish for supermarkets”, says Katrina Nakamura, fisheries scientist and director of the marine consultancy the Sustainability Incubator.

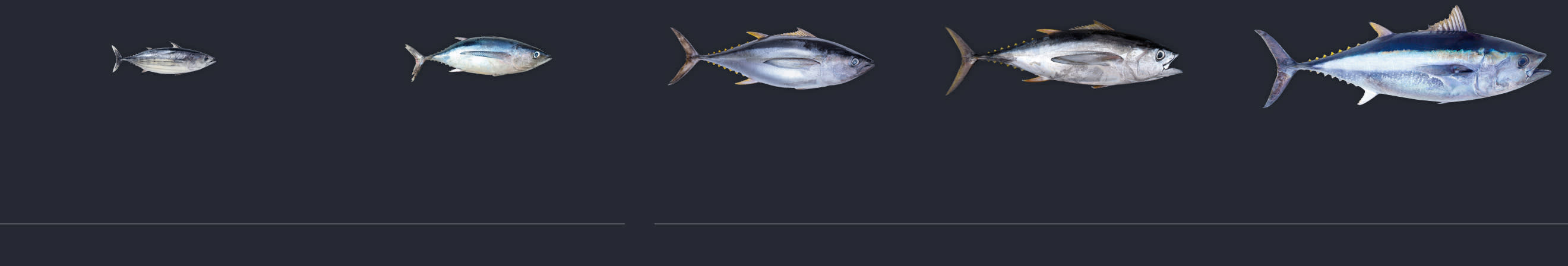

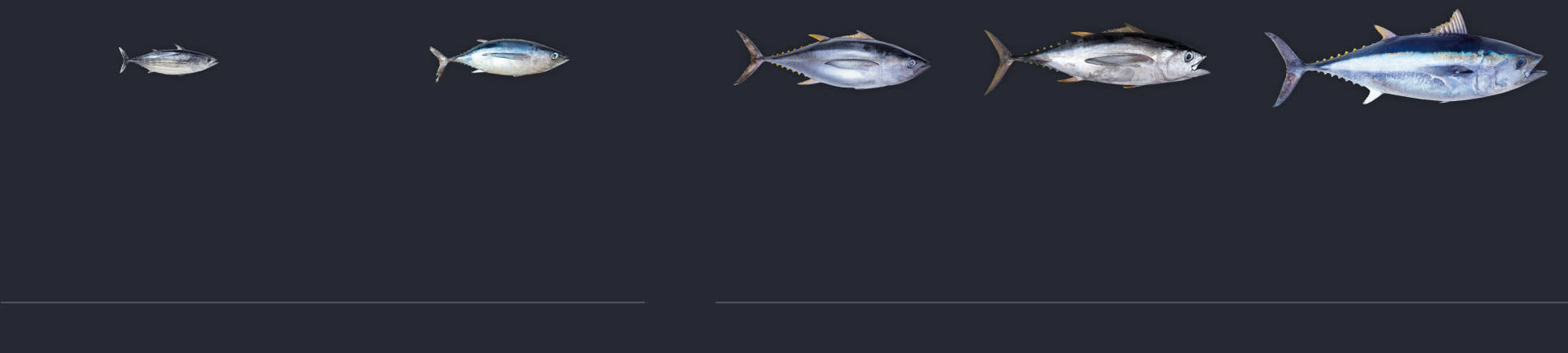

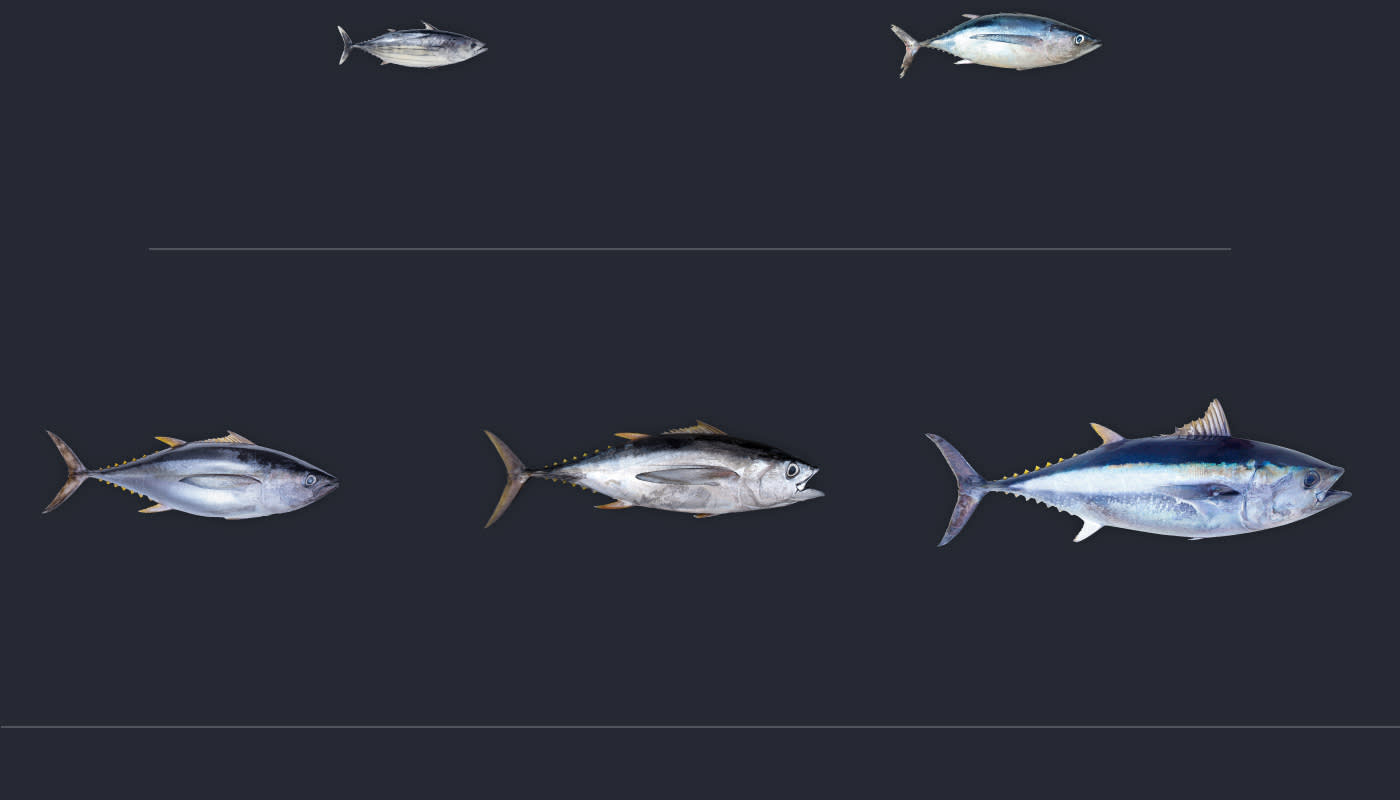

Japan remains the biggest destination for high-value tuna, a country favouring sashimi-grade bigeye and bluefin, while demand in Europe and the US is for canned products, mostly skipjack or albacore.

Tuna species serve different parts of the market

Graphic: Images of five main tuna species — skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye, albacore and bluefin — showing their size differences, key traits and status. Skipjack and albacore are generally not overfished, while yellowfin, bigeye and bluefin have some overfished stocks.

In the UK, where tuna is the country’s number one imported fish species by volume, 96 per cent of what is consumed comes in a tin.

The country imported about £11mn of chilled or frozen tuna last year, mostly albacore or yellowfin, compared with £535mn of cans, according to Export Genius data.

Three-quarters of this canned tuna comes from six countries — Ecuador, Mauritius, Seychelles, Ghana, Philippines and Thailand — with signs of exploitation also visible in their supply chains.

In Ghana, some workers and their representatives say there is widespread use of debt bonding, a lack of written contracts and the withholding of identity documents.

The country, along with other key UK supplier Ecuador, has also been yellow carded by the EU’s fishery warning system, which penalises those failing to tackle illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing — behaviour closely linked to human rights abuses.

But seafood supply chains are complex and notoriously hard to trace, often stretching far beyond what retailer labels or country-of-origin data suggest. Some products will show where the fish was processed rather than where it was caught, for example.

“There is never truly one single origin of any seafood sold at the supermarket,” says Nakamura, calling single-origin labels a “marketing illusion”.

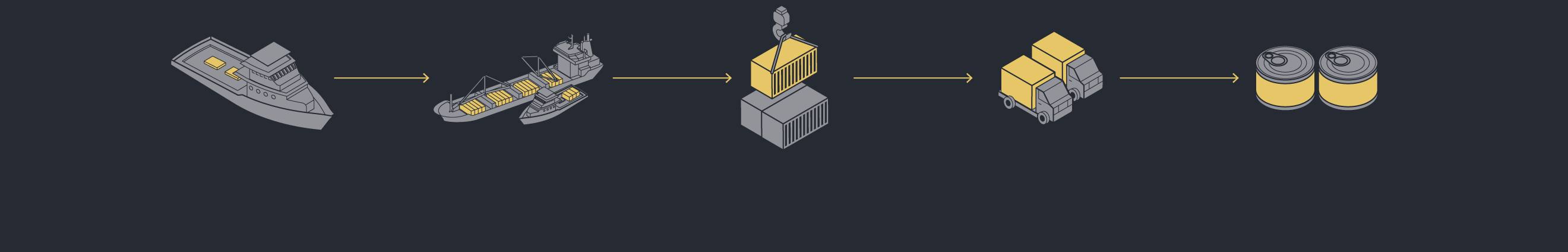

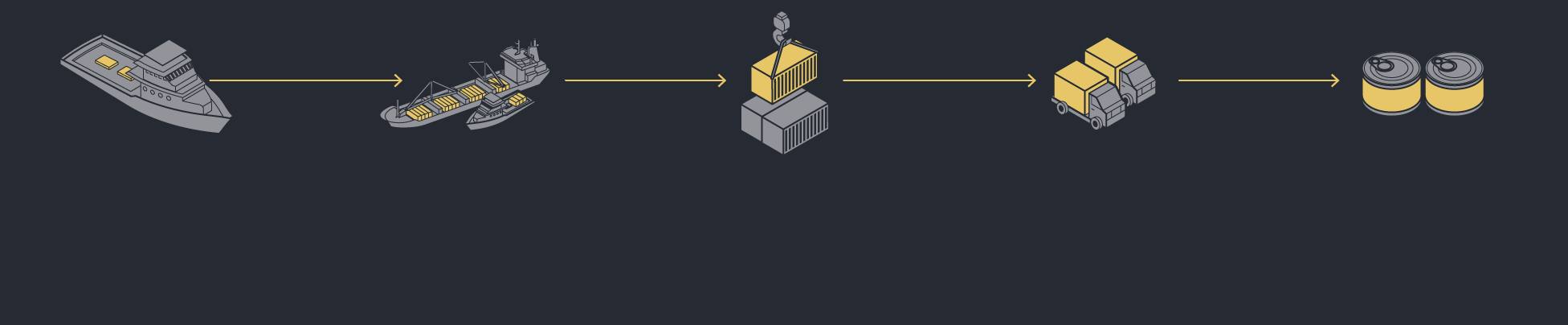

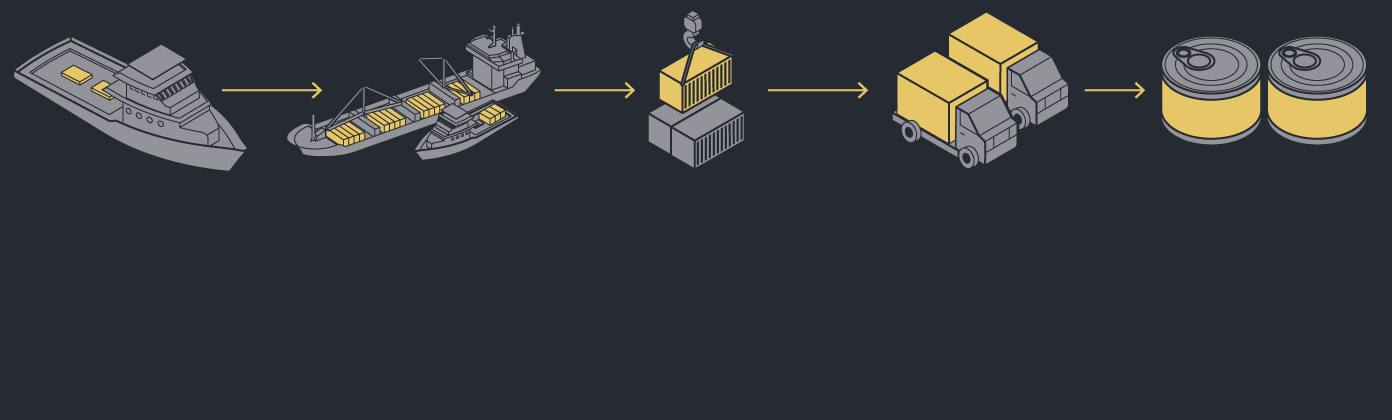

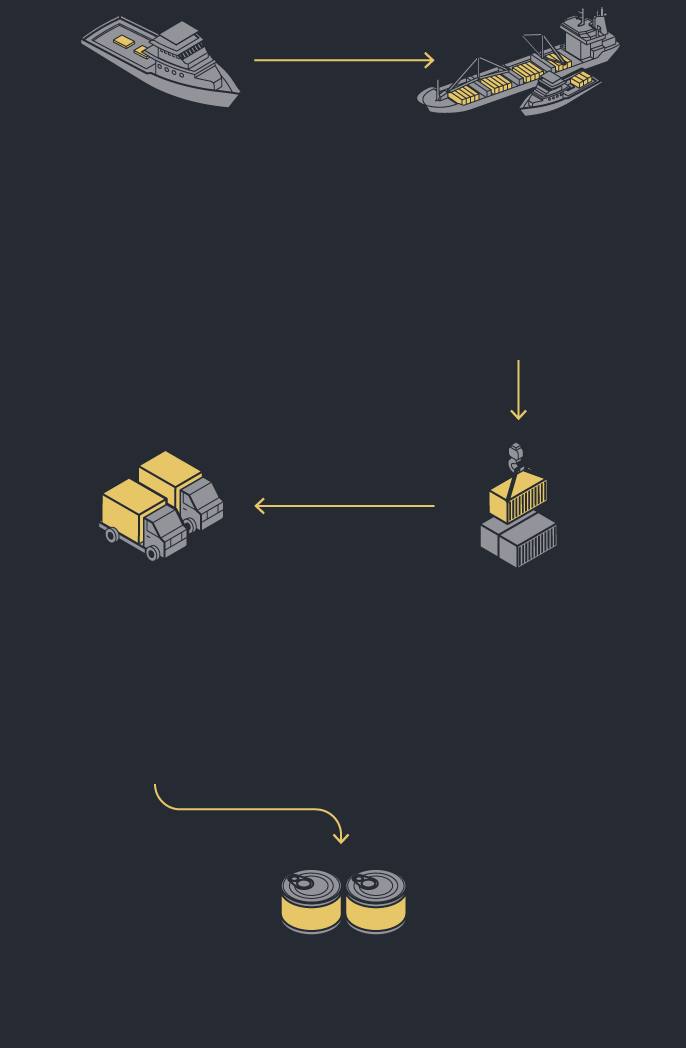

Tuna’s complex supply chain is dominated by retailers and brands

Graphic: Flow diagram of the tuna supply chain showing all the stages from fishing, transshipment and trade hubs to processing and retail. Large fleets catch the majority of tuna.

Traceability is further obscured by flags of convenience, which allow vessels to register under lax jurisdictions and hide their true owners. Bunanda’s Taiwanese vessel was reflagged to Vanuatu — the flag with the worst record in the Pacific region, one fishery expert with knowledge of regional infractions told the FT. Paperwork also shows some vessels supplying UK retailers have changed names, complicating efforts to track their records.

This has led Planet Tracker to estimate that up to 60 per cent of the world’s tuna catch could be untraceable, or “dark”, with Spain, South Korea, China and Japan among the worst offenders. The nations are among those flagged by the Global Slavery Index as high-risk for forced labour.

The FT connected abuses in some of these fleets to UK supermarket shelves using fishery details provided by retailers, data from the Ocean Disclosure Project — where companies voluntarily publish seafood sources — research into products in supermarkets, publicly available paperwork and interviews with workers.

One of the Chinese longline fisheries where workers reported abuses has been used by Wm Morrison, Tesco and Waitrose, while the other has supplied Morrisons, Asda, J Sainsbury and Tesco.

The supermarkets said they are urgently looking into the claims. Sainsbury’s added it had not sourced any own-brand products from Chinese or Taiwanese vessels for the last three years.

“Retailers are committed to upholding high standards of welfare for all people who work in their supply chains, and these allegations must be swiftly investigated,” said Sophie De Salis, sustainability policy adviser for the British Retail Consortium.

She added that although supermarkets are already working with external organisations to improve standards, they also want human rights and environmental due diligence to be made mandatory by the government to ensure an equal playing field.

China’s department of agriculture said it takes any allegations regarding its vessels seriously and is planning to investigate the claims. The country “resolutely opposes any form of forced labor” and has “strict regulatory requirements for the employment of crew members by fishing enterprises”, it added.

The South Korean longline fishery containing vessels spending extended periods of time at sea without visiting port is used by seven UK retailers, including Marks and Spencer.

Kang Dong-yang, a director at South Korea’s ministry of oceans and fisheries, said measures are being taken to improve conditions. These include ensuring a minimum of six hours’ consecutive rest each day and a period of port leave every 12 months. From next year, fishermen will receive a two-month break every 10 months, he added, with punishment for vessels violating rules.

Dongwon Industries, owner of the South Korean vessels, said it already guarantees crews six hours’ consecutive rest and five days’ annual port leave. Two of its vessels tracked by the FT have recently been sold, the company added.

The owners of Bunanda’s purse seine vessel said they “deeply regret” his health issues but denied they provided inadequate medical care or delayed treatment. They also said he was advised to seek medical attention before departure but declined. “The company acted strictly according to medical advice and regulatory compliance,” the owners added, paying for all costs related to his medical treatment and repatriation. They also denied he had his ID taken and said the payment of wages and fees were the responsibility of his Indonesian recruitment company. “The company remains committed to upholding human rights and social responsibility in overseas fisheries,” they added.

Taiwan’s Fisheries Agency said an investigation into the case concluded that there was no evidence delayed medical treatment led to Bunanda’s paralysis. There was also no evidence he was charged recruitment fees, that he was made to take out a loan, that he was misled about pay or that he had his ID taken.

Beyond certification

While international conventions on workers’ rights exist, enforcement is weak and major fishing nations — including China, Taiwan, South Korea, and the US — have yet to sign. The ILO, the UK and France want all countries with fishing fleets to ratify an ILO convention guaranteeing rights. Indonesia has committed to sign in 2026, and South Korea has indicated a phased introduction. New ILO guidelines for migrant fishermen were agreed at a meeting last month.

But rights groups say action can already be taken without such agreements — if existing international and national laws are enforced. Flag states, already legally responsible for vessel conditions, should ensure protections for migrant crews; home countries of migrant workers should tackle abusive recruiters; coastal states overseeing fisheries should monitor and deny access to offending vessels; and port states should inspect ships and hold violators accountable.

Consumer markets should also tighten port checks to stop seafood linked to forced labour from reaching consumers. Broader use of electronic and satellite monitoring would also strengthen enforcement and transparency, they say.

They also want to see retailers do more. Many of these technological fixes are “logistically deliverable” without significant cost, says the EJF’s Trent. “Corporate CEOs need to act — this isn’t about isolated cases, it’s about people’s lives.”

To do this, businesses should ensure their buying policies align with human rights goals, says Kelley Bell, social responsibility director for FishWise, which advises the industry. With “perfection” impossible, she says companies need to constantly review supply chains and flag and address issues.

This will require due diligence at vessel and recruitment level, says Chris Williams, responsible for the fisheries section of the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), “because that is how the forced labour journey begins”.

Fisheries scientist Nakamura says that instead many retailers continue to rely on “powerful” and increasingly popular certification schemes, such as the UK-based Marine Stewardship Council, which provides them with a “golden shield”. Bunanda’s fishery, as well as the two Chinese fisheries and South Korean fishery supplying UK retailers, carries the MSC’s blue tick logo.

While certification challenges cut across industries, from fashion to coffee, fishing is particularly vulnerable given the difficulties of monitoring vessels at sea.

Nakamura’s own research found that conditions aboard tuna vessels were untraceable for 74 per cent of catches certified by the MSC. The ITF, meanwhile, has recorded 39 forced labour cases across MSC fisheries in the five years to February 2025.

The MSC said that while it condemns the use of forced labour, it is an ecolabel focused on overfishing and the environment and “makes no social claims”. Allegations on vessels in MSC fisheries therefore “don’t fall within the scope” of its remit. It added that any accusations of forced labour are raised with fisheries, and that any entity convicted of forced or child labour “is excluded from our programme”.

Instead of certification pledges, what fishermen want is access to their fundamental labour rights — freedom of association, collective bargaining, as well as a means for grievance and remedy, representatives say. Above all, they want a seat at the table when decisions are made.

“If there is not any collective bargaining by independent trade unions at the national level, or through organisations like the ITF at the international level, there is no guarantee that workers rights are not being infringed,” says Williams.

Migrant seafarer and rights groups say a simple first step would be mandating onboard WiFi, which would enable fishermen to contact family, report abuse, connect to healthcare services and check pay. “Without access to communication, you can’t do any of that if you’re at sea,” says Gill, of Global Labour Justice.

All this comes too late for married father-of-two Bunanda, who is no longer able to work. After what he describes as a long legal battle, he has received a disability payout of about $40,000 but is still fighting for his full two-year salary and compensation.

He and his wife, Wati, describe what they experienced as a “people trade”.

“This is selling and buying humans,” Wati says.