Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Mancunian clubbing culture touched down in Mumbai last month as sunglasses-wearing ravers, some sporting bucket hats, converged inside a dark indoor arena, sheltered from the unseasonal drizzle outside.

Thumping beats and energetic sets from the likes of Norwegian-Indian electronic producer Suchi and Australian DJ Boring were part of the Indian debut of The Warehouse Project, a Manchester institution famed for its marathon year-end parties.

India’s live music scene is thriving. A young, increasingly affluent audience is luring more festivals and global artists to add India to their touring map.

In Mumbai, roadside billboards are advertising more upcoming gigs than I’ve ever seen before, from a K-Pop festival to Enrique Iglesias. International DJs, including Belgian techno titan Charlotte de Witte, are making stopovers, while global clubbing brands Boiler Room and DGTL have joined the local Sunburn electronic dance music festival.

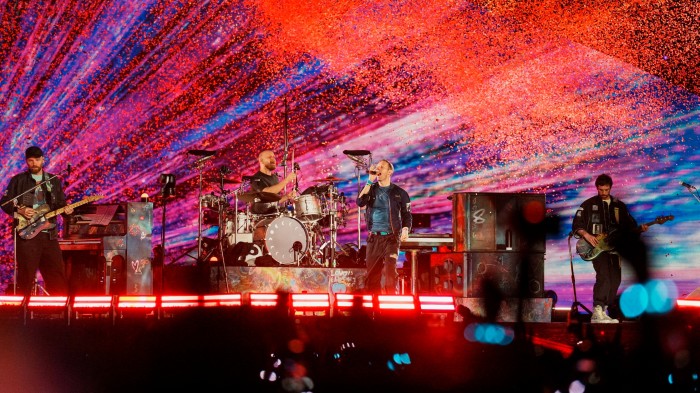

Following Coldplay’s sold-out performances in Mumbai and Ahmedabad over five days in January, Prime Minister Narendra Modi heralded India’s growing “concert economy”. The government has described the past year as a critical turning point for the Indian live events industry, pointing to major tours by Bollywood singer-songwriter Arijit Singh and Punjabi superstar Diljit Dosanjh as well as international stars such as Ed Sheeran.

This is all feeding into a $1.4bn live entertainment industry that EY expects to grow by nearly a fifth each year over the next three years.

By 2030, New Delhi wants the country to establish itself among the world’s top five live entertainment markets — joining the US, UK, South Korea and UAE.

Much work needs to be done before then. Beyond some cricket stadiums, India still struggles with a scarcity of international-standard venues.

Another problem, according to event planners, is the barriers presented by India’s infamously opaque red tape. Modi’s government acknowledges the problems faced by concert and festival organisers, who often have to obtain more than 10 separate permissions and permits per event.

“We always had a gun to our head in terms of who’s the next guy going to be coming to ask for a piece of the action,” said Joji George, a former live events veteran who helped to bring Bon Jovi to India in the 1990s and was involved in running Sunburn. “That hasn’t changed too much.”

Abrupt cancellations are frequent. Last year, Canadian DJ deadmau5 (known for performing in a large mouse helmet) was forced to call off a Mumbai show at the last minute amid security restrictions during Modi’s visit to the city.

And a club night planned here by Drumcode Records, the label run by Swedish techno don Adam Beyer, was scrapped without explanation earlier this year.

More recently, The Smashing Pumpkins said that they had pulled out of their maiden India tour last month “due to unexpected logistical challenges and conditions out of our control”. The result was that the band could not “perform these shows up to the standards that we and our fans expect”.

India Business Briefing

The Indian professional’s must-read on business and policy in the world’s fastest-growing big economy. Sign up for the newsletter here

New Delhi seems to be cognisant of these obstacles at least. India’s information ministry recently recommended a more simple national digital licensing system, funding for Indian artists and the construction of 25 to 30 “world-class, tech-ready” venues.

Event timings also present a challenge in Mumbai, where most bars and nightclubs close soon after midnight and after-parties tend to be held at home.

At The Warehouse Project’s party in Mumbai, the first set of DJs played to a sparse audience in the afternoon before the crowd filled out the dance floor a couple of hours before the end. Last-entry times earlier in the evening aren’t really part of the Indian culture yet, said promoter Mark Abbott.

“It’s something we’ll need to work on — finding ways to encourage people to arrive earlier and support the DJs who play first,” he added. “Of course, it didn’t help that we brought the rain over from Manchester.”