At a rare conference for international executives hosted by China’s biggest liquor maker last month, guests sipped on blueberry juice instead of Moutai’s signature spirit.

The teetotal banquet — which came after nationwide prohibitions on lavish government spending, including on alcohol, were expanded in May — is an example of a tougher terrain for the maker of baijiu, an intense spirit favoured by China’s former leader Mao Zedong and for decades a fixture of official functions.

Consumers are holding back on spending, as shown by the average wholesale price — what distributors charge retailers — of Moutai’s flagship 500ml Feitian product. The figure fell this month to Rmb1,620 ($230), its lowest level in about a decade.

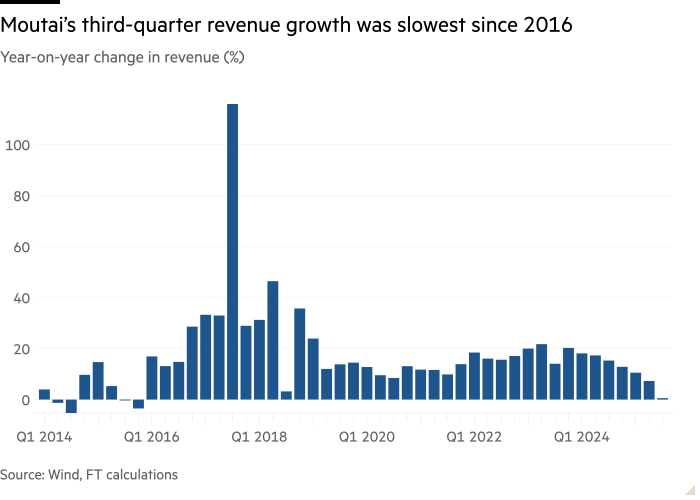

Third-quarter revenue was little changed year on year at Rmb39bn, the slowest pace of growth since 2016 and down from 9 per cent in the first half. Net profits were flat at Rmb19bn.

“Overall consumption in China [is] weak, and for baijiu it’s particularly weak because of the alcohol bans,” said Jennifer Song, an analyst at Morningstar, who pointed to outright revenue declines at some of Moutai’s competitors. “We see a clear downside for the whole sector.”

Founded in 1951 and ultimately owned by the government of Guizhou province, Moutai is closely watched as a barometer of consumer sentiment in the world’s second-largest economy.

Its share price surged from 2015 to 2021, at one point making it the world’s most valuable alcohol maker. But its market capitalisation has almost halved since its 2021 peak, with shares shedding 8.8 per cent in the past 12 months in contrast to a domestic stock market rally. Last week, it announced a share buyback of up to Rmb3bn, the latest in a series of repurchases.

In recent years, the company has focused on clawing back more value from the army of distributors that sells its product. Last month’s forum in Maotai, a mountain town in the landlocked province of Guizhou, also hinted at the need for new ideas.

The conference included a segment on “decoding Gen Z consumption”, highlighting the need to attract younger consumers to a drink traditionally associated with raucous work gatherings and business meetings.

The event’s programme reflects wider gloom in the global alcohol sector, where consumers, particularly younger ones, are drinking less. “The whole world is down,” said David Valentine, an adviser to several whisky distillery projects in China.

For Moutai, the event was an opportunity to showcase its 74-year history to representatives from some of the world’s biggest drinks makers, including France’s Pernod Ricard and Rémy Cointreau.

At a large square outside its main distillery, under a golden statue of former premier Zhou Enlai, who served Moutai during major diplomatic moments, the company’s staff assembled for an annual ritual in which apprentices honoured their baijiu masters.

But away from the festivities, the mood was more downbeat. “There aren’t as many [customers] as last year,” said a shopkeeper at one of dozens of riverfront shops selling different varieties of the sorghum-distilled spirit, some in large barrels. “The economy isn’t good.”

Moutai carefully controls the supply of its products, especially Feitian, which is sold through licensed vendors and makes up an estimated 85 per cent of total sales, according to Bernstein. In 2023, the company increased ex-factory prices 20 per cent to Rmb1,169 as part of a push to capture more value from distributors.

Euan McLeish, analyst at Bernstein, said the company’s margins were “still very strong” even if wholesale market prices were down. “The overall value chain has shrunk, that’s a fact, it’s undeniable,” he said. “Who’s taken the hit? It’s the distributor.”

Morningstar’s Song suggested there were concerns about inventory levels in the market and their effect on prices, given Moutai has in the past been purchased as a luxury good or investment product.

“When the price goes up, people will accumulate inventory,” she said. “When the price comes down, people will sell the inventory.”

Moutai also sells several cheaper varieties of baijiu, including a “series” segment for which sales are down 8 per cent this year and slumped 34 per cent in the third quarter, based on Song’s calculations.

The company has made some attempts to appeal to younger consumers with new products. In the hotel hosting Moutai’s event last month, its ice cream products were prominently displayed, and at a cultural area in the town it was selling branded toys.

Moutai did not respond to requests for comment.

At the conference, representatives from makers of Scottish whisky, Polish vodka, French wine and cachaça, a Brazilian drink made from sugar cane, mingled with Chinese executives, reflecting continued interest in China’s vast market despite slowing momentum.

“China is 10 times bigger than Brazil,” said Mário Morais Marques, president of Brazilian group Dona Beja, who hopes to launch in the mainland. “We’re going to come back.”