Mrinalini Mukherjee’s “Pakshi” (1985) takes centre stage like a commanding deity at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, its towering rose-pink and muted-gold form made from dyed hemp, masterfully hand-knotted using ancient macramé techniques. The enigmatic suspended sculpture, calling to mind fishermen’s ropes as much as totemic masks, is both figurative and abstract, fusing and refining influences from botany and rural handicrafts to classical Indian dance-theatre and temple sculpture.

Mukherjee’s last major show in the UK was more than 30 years ago at Oxford’s Museum of Modern Art (now Modern Art Oxford), when her monumental, anthropomorphic soft sculptures were apt to be misconstrued as folkloric, or even religious. More recent retrospectives, in New Delhi in 2015 (shortly before her death that year) and the posthumous Phenomenal Nature in 2019 — her first in the US — at the Met Breuer in New York, have fuelled her growing recognition as a daring and path-breaking modernist. “Pakshi” was among her “deities” shown at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

Tracing her influences and affinities, A Story of South Asian Art: Mrinalini Mukherjee and Her Circle is the first exhibition to present her work alongside that of her family, friends and mentors. A companion retrospective, also curated by the RA’s Tarini Malik, is to open at the Hepworth Wakefield in West Yorkshire next May. That show, Malik tells me, will present Mukherjee’s work with that of her mother, Leela Mukherjee (1916-2002), and other women sculptors from South Asia who worked independently of each other.

By contrast, the RA’s group exhibition situates Mukherjee’s life and work within creative networks that “gave rise to new modernisms”. As the occluded history of global modernisms slowly enters major institutions, from the 2013 Tate retrospective of Ibrahim El-Salahi of Sudan’s Khartoum School, and The Casablanca Art School at Tate St Ives, to this year’s Brasil! Brasil! at the RA and Nigerian Modernism now at Tate Modern, the remarkable birth of early-20th-century Indian modernism remains relatively unfamiliar to many audiences. However, this London show touches only tangentially on that story.

Commendable effort has gone into selecting and sourcing some rare and astonishing works. Of almost 100 on show (Mrinalini’s are distinguished by black labels), most have never been seen outside India. Three rooms in the Sackler Wing are devoted to three locations pivotal to her development: Santiniketan in West Bengal, home to the utopian “world university”, the Visva-Bharati, where both her parents studied; Baroda (Vadodara) in Gujarat, where she was a student in the 1960s from age 16; and Delhi, where she moved in the early 1970s.

Born in post-partition Bombay in 1949, Mrinalini spent her childhood summers in Santiniketan, the centre for art founded in 1901 by the poet and painter Rabindranath Tagore, the 1913 Nobel literature laureate. Her father, Benode Behari Mukherjee (1904-1980), was one of the first students, and later a teacher, at Kala Bhavana, the institute of fine arts that Tagore opened in 1919 — shortly after renouncing his knighthood in protest at the Amritsar (Jallianwala Bagh) massacre by British troops. Described here as a “crucible for modernism”, the institute held open-air classrooms while spurning the British Raj’s academic art, embracing a pan-Asian modernity and assailing distinctions between art and craft.

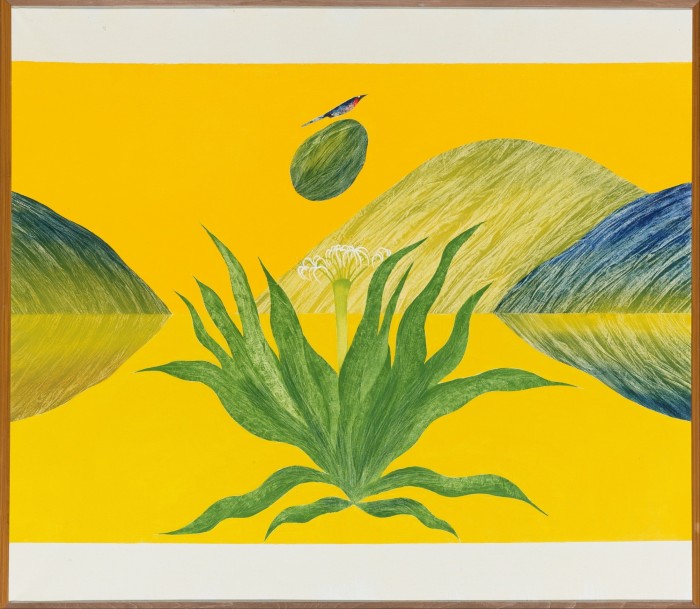

A pioneer of a movement later dubbed contextual modernism, her father renounced fashionable mythological subjects for the nature around him. His early works here include an untitled watercolour from 1936 of a Japanese mother and child, reflecting travels and exchange with east Asia, and “Mussoorie” (1952), a diluted watercolour evoking the dramatic mists of the Himalayan foothills. Born blind in one eye and acutely myopic in the other, he was the subject of Satyajit Ray’s documentary The Inner Eye (1972). Most astounding are the Matisse-like cut-out collages of startling vivacity and colour that he made after losing his eyesight completely in 1953, such as the angular “Reclining Man” (1957) and “Lady with Fruit” (1957). Mrinalini, his only child, would describe plants to him on their walks. The show suggests that his blindness and reliance on touch influenced his daughter’s intuitive, tactile approach, sculpting without preparatory plans in what she termed an “organic unfolding”.

Leela Mukherjee began sculpting in wood after visiting Nepal. Her wooden sculpture series Intertwined Figures is shown alongside her daughter’s “Burgeoning Cluster” (c1997), a ceramic work that disquietingly fuses botanical and bodily shapes. Mrinalini’s labia-like hemp-and-steel “Jauba” (2000) is abstract but unmistakably anatomical. Yet beguiling etchings from the 1970s and ’80s of three-striped palm squirrels — never shown in her lifetime — suggest her intimate and closely observed relationship with nature.

Her father’s student KG Subramanyan (1924-2016) taught Mrinalini at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda, a cosmopolitan hub for postcolonial experimentation. He was renowned for monumental murals, and his works here include an acrylic painting from 1980 of a reclining woman that recalls both Picasso and Bengali Kalighat painting; a striking, semi-abstract bird’s-eye-view oil painting of bathers, “Banaras Ghat” (1965); and rare surviving fragments of his woven textiles from the late 1950s. Mrinalini’s first fibre works from sunn, a local hemp, were made for Baroda’s Fine Arts Fair, which he co-founded in 1961 for students mining what he extolled as India’s “living traditions”.

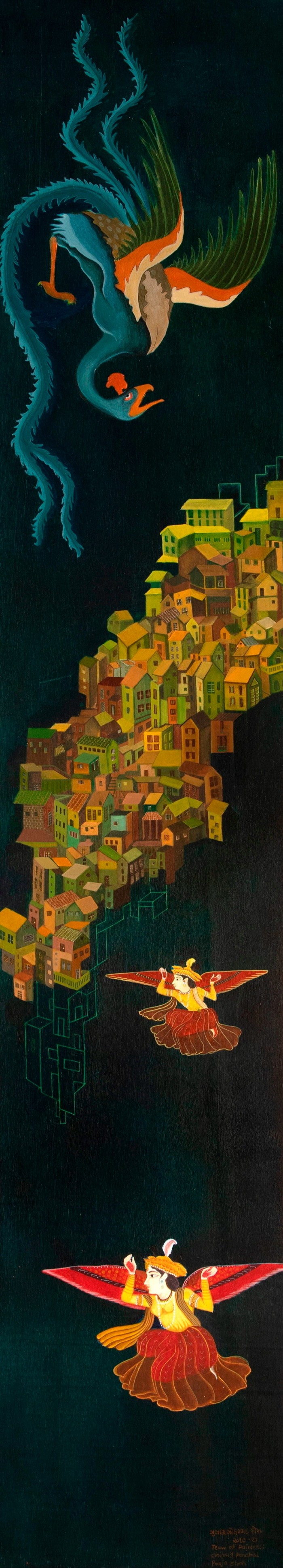

Travelling across India and beyond, Mrinalini took copious photographs of festivals and temples (not shown here). She went on field trips with friends whose compelling art is also on show. Nilima Sheikh’s (b 1945) luminous painted scroll series, Songspace (1995), and Gulammohammed Sheikh’s (b 1937) miniature-inspired acrylic scrolls Simurgh and the Paris (2019) recall Santiniketan’s pan-Asian vision.

In Delhi, Mrinalini’s sculptures boldly left the walls. An accompanying guide suggests that this mature transformation was fuelled by her friendship with the artist Jagdish Swaminathan (1928-1994), a communist and strong advocate of Indigenous art, whose earth-coloured abstract paintings are on show. There is a video montage of photographic portraits at the outset, but strangely little insight into these personalities (though many were also writers) or their relationships. Did Subramanyan’s Gandhian activism steer his student’s choice of humble materials? Who was the Mrinalini who rode around India with her then husband, the architect Ranjit Singh, on a motorbike? Subramanyan and Gulammohammed Sheikh allude starkly to communal riots in some of these works, while Nilima Sheikh depicts atrocities in Kashmir. What was Mrinalini’s stance, or her view of Indira Gandhi’s Indian Emergency of 1975-77 soon after she moved to Delhi, which galvanised so many of her fellow artists — as seen in last year’s exemplary Barbican show, The Imaginary Institution of India?

According to its curator, this is the RA’s first exhibition of South Asian modern and contemporary art. Rather than sparing visitors an overload of arcane history, the contextual lacunas make this seem more a show, perhaps, for the initiated connoisseur. One hopes the Hepworth Wakefield exhibition to follow will fill in the gaps.

To February 24 2026, royalacademy.org.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning