Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It was 3am in Australia when Art Malone received a call telling him his company Graphinex was set for a A$1.3bn ($860mn) loan as part of a US-driven initiative to develop an alternative to China’s rare earths and critical minerals supply chain.

“I fell out of bed when I heard the number,” said Malone, marvelling at how the graphene company’s fortunes had changed so quickly. At a mining conference this week “I felt like a rock star”, he said.

Companies such as Graphinex, which is developing the world’s third-biggest deposit of graphene, have long been out of favour with investors who wondered if they could ever compete with China, he said.

This week’s US-Australia deal has rewarded those “at the front of the curve,” he said.

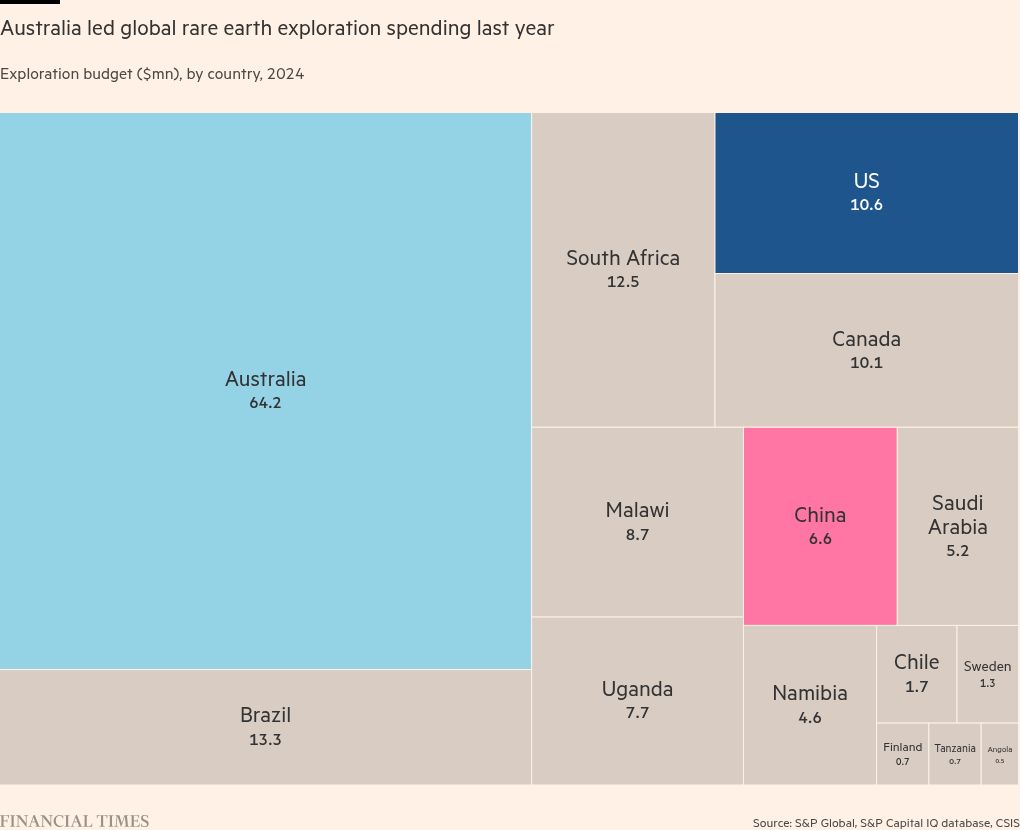

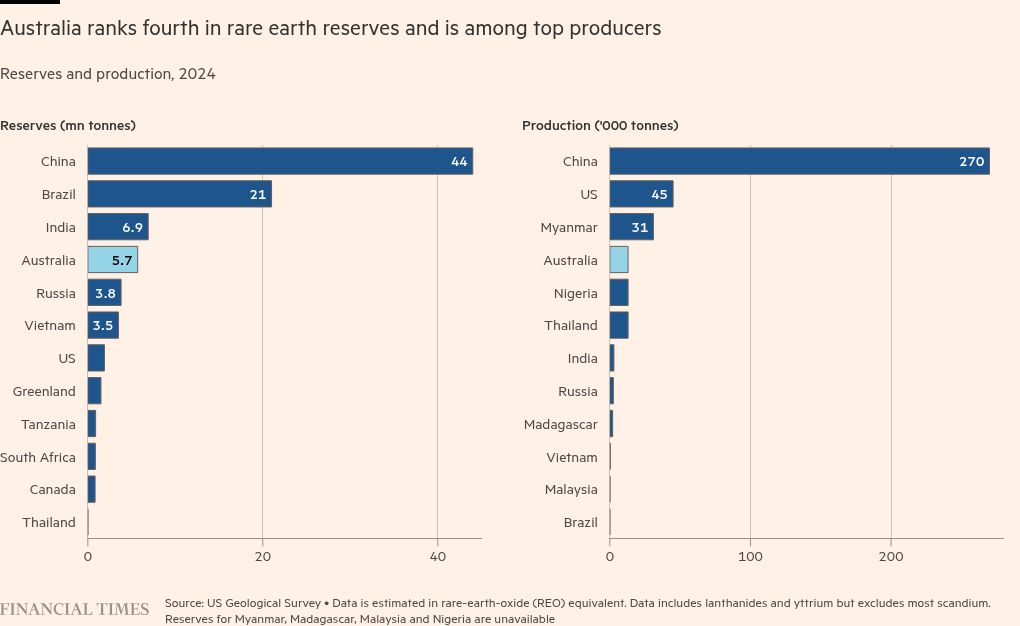

Australia has emerged as a key partner for the US as China has weaponised its grip on the supply chain, imposing export controls on its domestic industry amid trade negotiations with Washington.

This week the Trump administration signed an agreement at the White House with Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese for each country to invest about $1bn in the coming months to foster the creation of a non-Chinese supply line of rare earths and other critical minerals.

The US Export-Import Bank signed loan commitments worth more than $2.2bn to advance critical minerals projects in Australia with an initial seven companies including Arafura Rare Earths, Northern Minerals, RZ Resources and Malone’s Graphinex.

Doug Burgum, the US secretary of the interior who is driving the critical minerals alliance, described the deals, alongside the race to develop AI technology, “as important as the Manhattan Project” — which led to the creation of nuclear weapons.

The flurry of deals underscores the surging values of a host of hitherto obscure Australian miners.

Those who bought into the Australian rare earths vision early — ranging from iron ore billionaire Gina Rinehart and Japanese oil companies to the offices of some of the country’s richest families — have enjoyed a bonanza as shares soared ahead of the landmark deal.

Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting took a stake in Lynas Rare Earths, the largest producer of rare earths outside China, in 2020 and has since backed nascent projects such as Arafura, small-cap ASX-listed explorers St George Mining and Brazilian Rare Earths as well as US player MP Materials, all of which have soared in value in the past six months.

The Australian government this week bought a $100mn stake in Arafura as part of its rare earths drive.

US and Australian officials identified the Arafura development, north of Alice Springs, and a gallium refinery in Western Australia being built by Alcoa and Japan’s Sojitz, as priority projects. Gallium is an essential ingredient for semiconductors and defence technology.

Dim Ariyasinghe, an analyst with UBS, described rare earths as equivalent to “spice” for the global transport, robotics and defence industries in that the volumes needed are small but the ingredients are critical.

While companies such as Lynas have seen their share prices soar, some smaller players have struggled to find financing due to concerns about competition with the established and powerful Chinese industry.

High energy and labour costs make the cost of construction of rare earth refineries in Australia almost five times that of Asia, according to analysts.

The Australian government has provided subsidies for projects, such as heavy backing for the A$1.8bn Iluka Resources refinery in Western Australia, to stimulate the industry.

Some question if these subsidies will be enough to make Australian output competitive vis-à-vis China. “Why would you want to spend taxpayer’s money in Australia to solve other people’s problems?” said Thomas Kruemmer, a rare earths specialist and director of Ginger International Trade & Investment. “There is no market for rare earths here,” he said.

But Dominic Raab, the former deputy prime minister of the UK and now head of global affairs at investor Appian Capital, told the Financial Times that subsidies are required to kick-start the rare earths sector. “Fundamentally the market is broken in this space. The challenge for the whole west is how to build those supply chains,” he said.

Appian is invested in Gippsland Critical Minerals, to the east of Melbourne, said Raab. “It’s exactly the type of project that will get rocket boosters from this framework. It’s a great local project with major geopolitical consequences.”

Campbell Jones, chief executive of RZ Resources which is developing a mineral sands mine in New South Wales and a separation plant in Brisbane, said that the extent of the interest became clear when US officials invited 20 Australian companies to Washington last month. “That has provided confidence to the market that this is real,” he said.

Adam Handley, chair of Northern Minerals, said there was a “palpable” sense of goodwill in Washington. “We’ve moved from the stage of cautious optimism to a sense of excitement about what can be achieved. Not just as companies but as nations,” he said.