As a state guest house, the Akasaka Palace in central Tokyo is used to playing host to visiting dignitaries. Last month, however, former prime minister Fumio Kishida wooed a different kind of crowd: the guests of US private equity group KKR.

Over dinner for almost a hundred of Japan’s corporate executives and their bankers, Kishida extolled the virtues of private equity and why the country needed the financiers in the room.

It was a far cry from when private equity first entered Japan a quarter of a century ago, when newspapers decried firms as vulture funds and politicians steered clear of public contact.

Now private equity in Japan is in the ascendancy and the establishment is courting the firms to help shake up moribund corporates and spur industry consolidation.

“The idea of introducing a shock to the system . . . literally to create a crisis, is a very welcome one in the establishment,” said Jesper Koll, director of the activist Japan Catalyst Fund.

Private equity has already made its way into between 10 and 15 per cent of big Japanese companies, David Gross, Bain Capital’s managing partner in Asia, estimated. “The future”, he said, is “the next 80 to 85 per cent”.

The industry’s Japanese makeover has been achieved in part through solid returns — 2.4 times the equity capital invested between 2010 and 2024, according to consultancy Bain & Co, better than any other major market — and by the extremely careful cultivation of its public image.

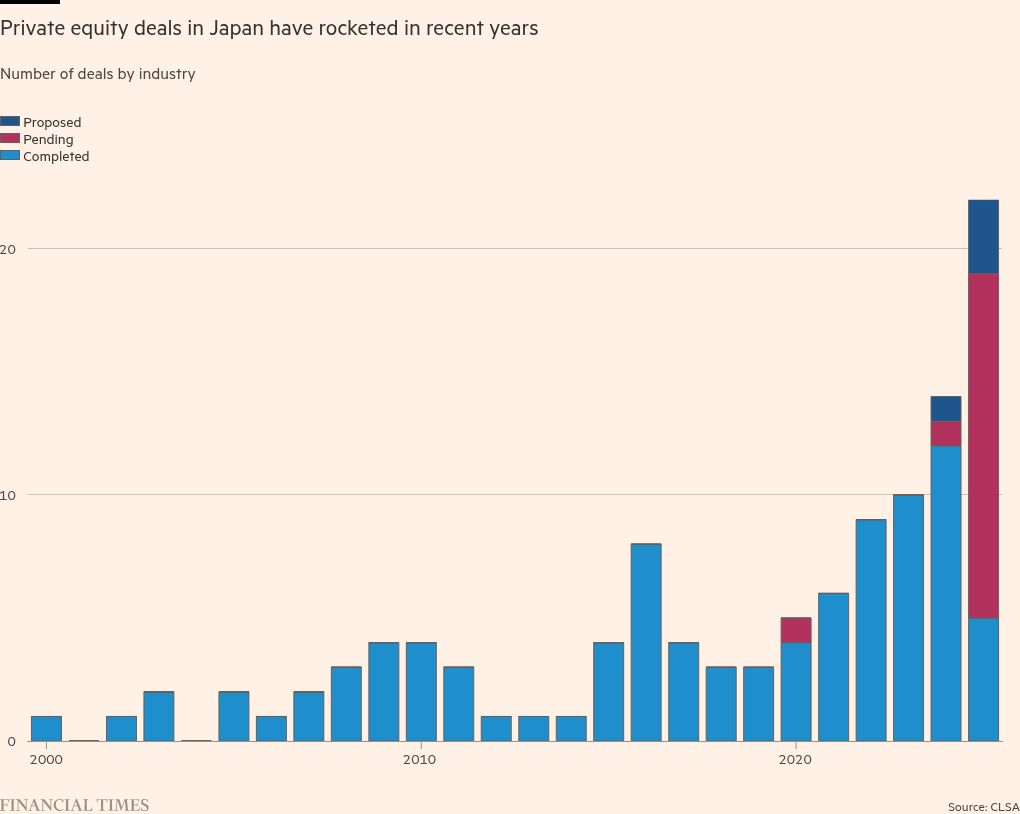

The biggest firms — Carlyle, Bain, KKR and Blackstone — landed in Japan in the years after the country’s postwar bubble had burst, and at the start, the number of deals being done was extremely low and the businesses up for sale tended to be distressed, marginal assets.

“The first 10 years of private equity in Japan, up until roughly the Lehman shock, was essentially just an incubation phase. People didn’t know us or what private equity was really about,” said Takaomi Tomioka, co-head at Carlyle Japan.

Private equity started to break into the establishment with founder-led deals with well-known companies from pizza chain Domino’s to family restaurant group Skylark.

But a new era of carve-outs that started with a KKR-Panasonic Healthcare deal has extended the industry’s reach into everything from defence to semiconductors.

Rare public failures, such as KKR-owned car-parts supplier Marelli tumbling twice in bankruptcy, have rocked the market and tightened financing for a period, but have proved fleeting.

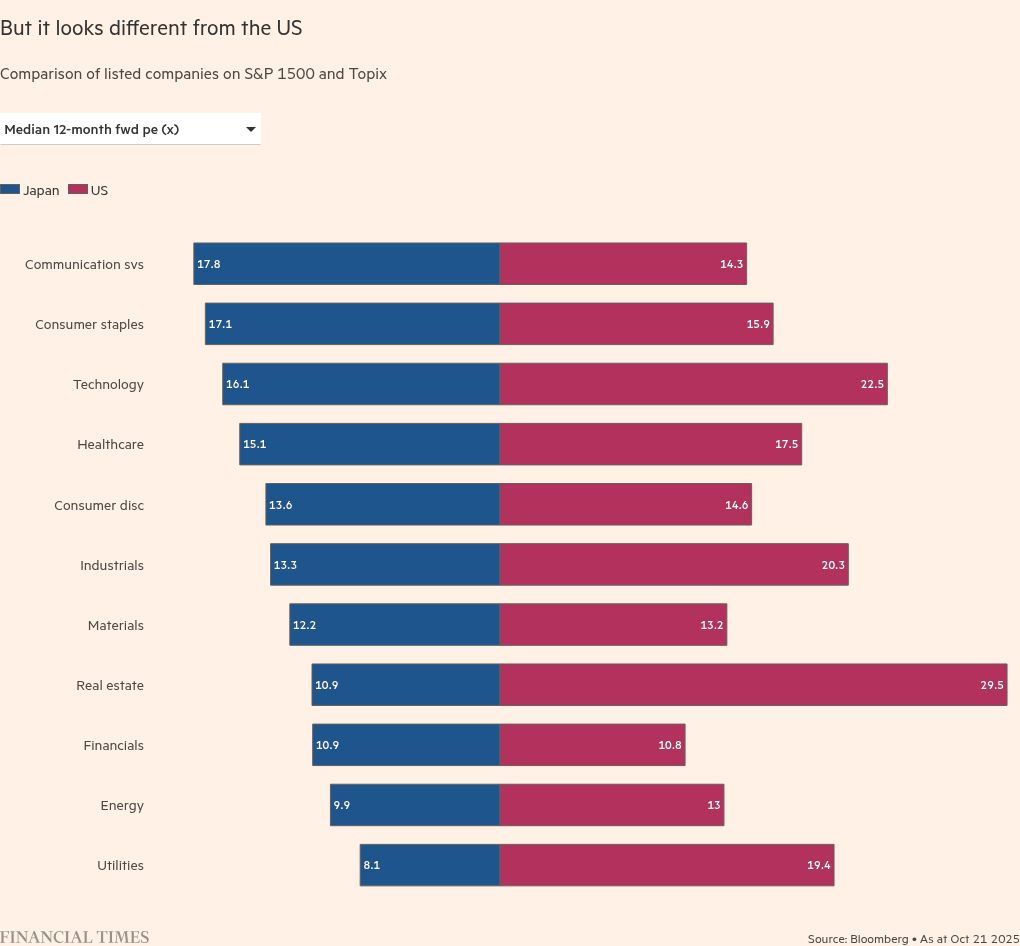

“Compared to the US, we are still 10 to 15 years behind in terms of how CEOs think about corporate governance . . . we have just started to see the mindset change,” said Hirofumi Hirano, the head of KKR in Japan.

There are now estimated to be between 150 and 200 private equity firms in Tokyo and the market has grown more sophisticated.

But it is also growing far more competitive, both for deals and staff. Introductions to executives are prized, and can cost tens of thousands of dollars in fees to intermediaries, according to people familiar with the matter.

Winning auctions is increasingly expensive, even if a bidder can secure the backing of Japan’s biggest banks, which will often only give credit to three firms vying for a deal.

Private equity groups are starting to push the frontiers of the market as a result.

Firms, particularly those that are smaller or newer to the market, are being forced to get more creative about structures, joining forces with bigger rivals or simply buying companies from other firms.

“It used to be just about control, there was no hybrid or minority stakes. That is changing,” said Naoya Shiota, who recently joined law firm Morrison Foerster’s private equity team.

An all-out fight between KKR and Bain for Fujisoft, which was kicked off by activists and then flirted with going hostile as the price was ratcheted up, has been taken by many as another key sign the market in Tokyo is becoming more mature, rather than as a demonstration of PE’s excess.

“It’s really fascinating . . . to see how the institutions of Japan have embraced this idea of reform and activism when in the past it was just getting lip service,” said Jean Salata, head of private capital in Asia for EQT, even as he pushed back against the need for hostile deals.

But as activists push companies and founders into sales to private equity at ever greater rates and those buyout firms penetrate deeper into the core of Japanese industry, nerves however are slowly setting in.

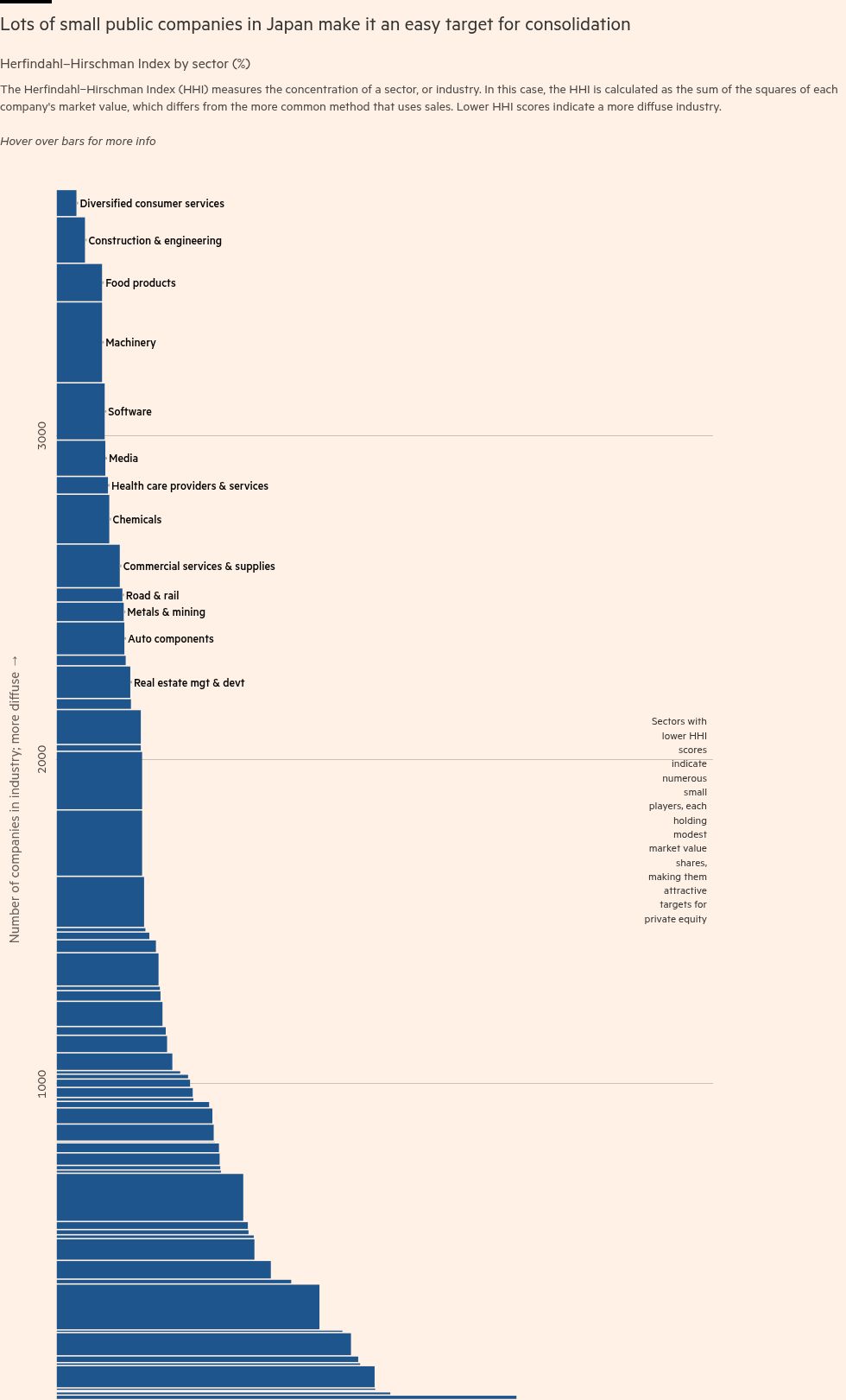

“The big international private equity guys, Bain, Carlyle, KKR, EQT, could easily end up owning 30 to 40 per cent of the SME market,” said Alicia Ogawa, a board member at the Nippon Active Value Fund and an expert in Japanese governance reform.

“Yes, that’s good for the macro economy — Japan doesn’t need so many auto parts companies or ball bearing companies — but wouldn’t it be better for Japanese CEOs to take control of their own destinies, for the country’s public markets to sort this out themselves?”

Bain and Blackstone are already making a major push into Japan’s third city of Osaka where activists are also making inroads.

“For Japan, this is less about private equity and more about the basic idea of financialisation,” said Andrew McDermott, a longtime Japan investor and president of Mission Value Partners.

“America’s public companies today are often indistinguishable from private equity companies . . . Japanese public companies are not perfect, but they are generally run by people who understand the underlying business and care about the company’s future,” he added.

Privately, government officials say that they still see the benefits of private equity but are closely monitoring for signs of excess. Some investors are also growing jittery about the leverage being used.

Bankers estimate that a Japanese portfolio company will now typically be leveraged around 5-7 times; closer to 8 or 9 times for those in particularly attractive sectors and with use of riskier mezzanine financing.

Banks that became nervous after the failure of Marelli are now back offering more aggressive terms, according to private equity advisers.

Buyout executives admit that exits over the next five years will be the real test, with higher prices at auctions meaning returns could come under pressure.

Firms are also conscious that public sentiment — or simply market conditions — could yet turn against them, especially as the industry’s reach extends further into regional companies where managers are less comfortable with financial engineering.

Private equity might only be tolerated so long as it remains useful in driving the country’s manufacturing base.

“Finance is not just about finance,” said Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike said. “It’s not something that can exist on its own.”

One private equity executive in Tokyo said the reality was “enormous pressure from investors to deploy, deploy, deploy” and that “price doesn’t matter the way it should”.

“We can’t just stop doing deals. It’s a rollercoaster and it is getting dangerous,” the executive added.

Atsuhiko Sakamoto, head of private equity in Japan for Blackstone, cautioned that those entering Japan now might not realise how different the market still is.

“Remember, the backlash in the US came from buying legacy industrial businesses in the 80s and 90s and slashing headcount . . . the key people in Japanese PE are very aware of that history,” he said.

“For at least the next five years, I don’t think there will be a need for more aggressive cutting of jobs. But maybe as more people come in, those that don’t know the history in Japan . . . maybe they get overconfident and think they can do anything.”