Welcome back. China’s state-driven ascent towards global manufacturing and technological leadership is remarkable.

However, as industrial policy gains favour among governments worldwide, this week I explore a telling contradiction in Beijing’s model: impressive innovation coupled with little meaningful productivity growth.

Since Xi Jinping became China’s president in 2013, the Chinese Communist party has doubled down on creating industrial and technological self-reliance, building on decades of long-term economic planning.

“An array of state instruments have been deployed to drive the project,” says Mark Williams, chief Asia economist at Capital Economics. “This includes grants, tax breaks, loan guarantees and public procurement support for every link of the supply chain, from raw materials to research and development.”

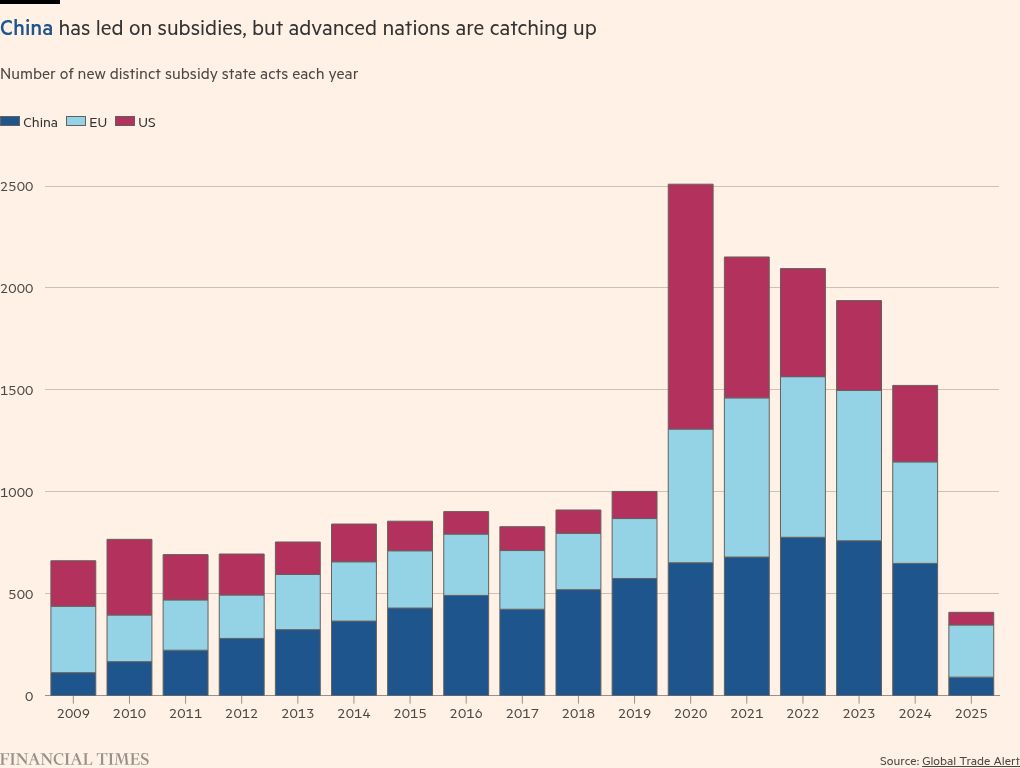

Data from the Global Trade Alert shows that China has implemented more than 7,500 subsidy policies since 2009. Between 2009 and 2022, Beijing’s total subsidy count was equal to about two-thirds of all those adopted by G20 advanced economies combined, according to the IMF.

The measures have been largely successful at elevating Chinese innovation and industry, as I outlined in the January 19 edition of this newsletter.

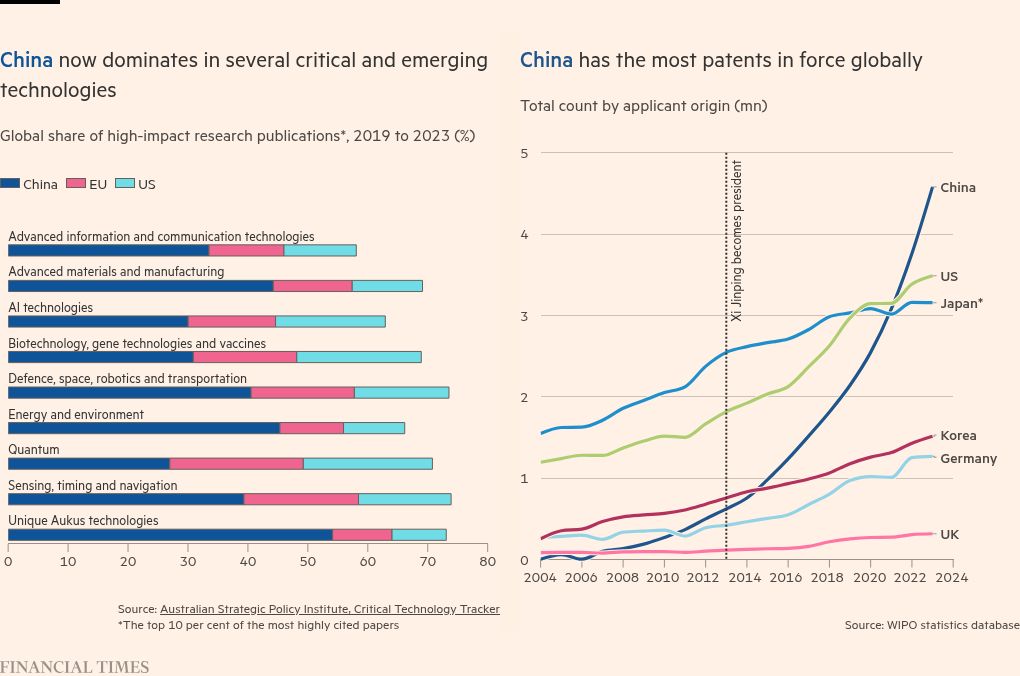

China led in just three of 64 critical technologies between 2003 and 2007, but had become the top country in 57 of those technologies between 2019 and 2023, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Today, China is the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles, batteries and many renewable technologies. In frontier technologies, it is closing in on the US’s number-one position in biotechnology and quantum, according to Harvard University’s Critical and Emerging Technologies index. DeepSeek’s emergence in January also highlighted a growing expertise in artificial intelligence.

The country’s broader innovation ecosystem has matured too. Chinese universities churn out far more Stem PhDs than in the US. Since 2013, annual R&D spending has increased by over $480bn in purchasing power parity terms — more than in the US. And, crucially, Chinese firms have become increasingly adept at exporting products in high-end sectors that use predominantly domestic tech.

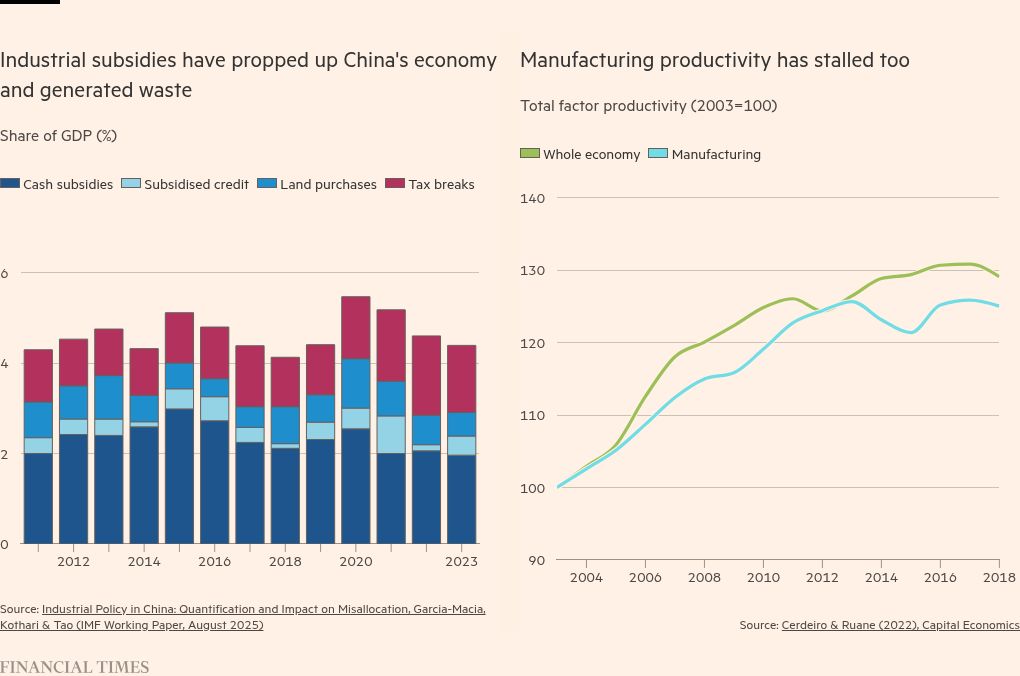

But Beijing’s manufacturing and innovation boom has not translated into notable productivity gains.

In particular, Xi’s desire for “high-quality development” centres on driving improvements in total factor productivity (that is, how efficiently workers and capital are combined).

Estimates of China’s TFP by the IMF, Asian Development Bank, the Conference Board and Penn World Table all suggest its annual growth has slowed since the late 2000s. Some even point to outright decline in the late-2010s.

At comparable levels of development, China’s TFP growth has also underperformed east Asian “miracle” economies by a wide margin, according to analysis by the Lowy Institute.

In more recent years, China’s potential growth rate has been revised down by many forecasters too.

“It takes time for innovation to boost growth, but this lag doesn’t explain why productivity has slowed so substantially or been weaker than other rich economies,” says Capital Economics’ Williams. “Something more structural is at play.”

“The point when productivity growth began to disappoint in China coincides almost exactly with the pivot to prioritising technological leadership after the global financial crisis,” he adds.

Several factors might contribute to weak TFP growth, such as China’s property crash, poor demand and mismeasurement, but wasteful industrial policy is the prime suspect.

An IMF working paper published in August underscores this. It estimates that industrial policy measures could have reduced China’s TFP by around 1.2 per cent, and its GDP by 2 per cent.

Aside from the sheer cost of subsidies — which the researchers calculate to be about 4.4 per cent of China’s GDP in 2023 — Beijing’s largesse has supported inefficiency, driven overcapacity and created huge financial losses.

Subsidies have tended to flow to better-connected firms — not necessarily the most efficient ones — and have created barriers to entry for others, notes Adam Wolfe, emerging markets economist at Absolute Strategy Research.

“Local officials tend to subsidise the same industries and then protect firms in their jurisdiction from competition,” says Wolfe. “The reallocation of credit to high-tech manufacturing should, in theory, boost TFP. But it has been more than offset, in practice, by the misallocation of labour and capital due to duplicative local subsidies and suppressed market exits.”

Indeed, interventionism tilts the playing field against other productivity-enhancing opportunities, including start-up growth. For instance, crowded out by government support, private venture capital finance has dried up. Other analysis suggests state subsidies may have induced companies to focus on low-risk and safer projects to secure funding.

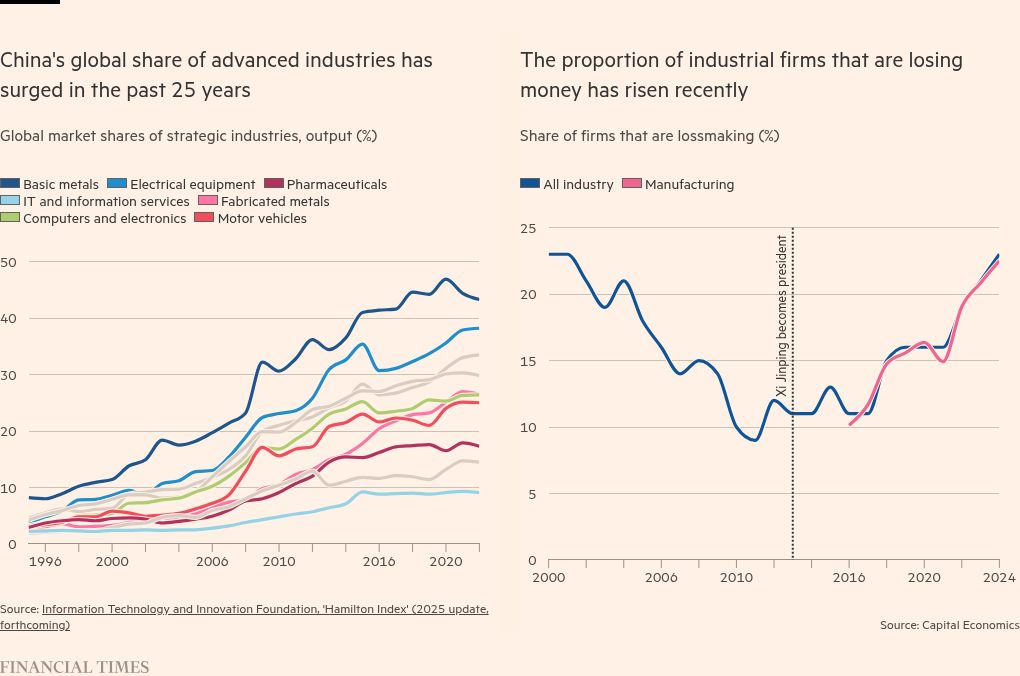

The rush to enter high-tech sectors and win state support has also led to overproduction and fierce price competition, or “involution”. Ports are turned into EV car parks; AI chips lie idle in newly constructed data centres. The surplus is harder to export abroad, as trade partners have cottoned on to the risk of dumping.

Nonetheless, by luring companies with financial incentives, some have been able to gain a foothold, rapidly generate profit, boost market share and benefit from economies of scale.

In this way, Beijing’s industrial policy has raised output in strategic sectors, nurtured entire industries, from shipbuilding to chipmaking, and built domestic champions such as EV maker BYD.

But it has come with waste and a high cost. For each BYD, there are scores of firms that make losses and eventually collapse.

The share of lossmaking Chinese manufacturing companies has risen since 2013, and rapidly so in the past few years. Analysis by ASR finds over one-quarter of listed non-financial firms had an earnings before interest and tax-to-interest coverage ratio below 1 last year, up from around 10 per cent in 2018.

“Essentially, China has pivoted from one kind of inefficient over-investment in real estate to another,” says Roland Rajah, lead economist at the Lowy Institute. “Sure, industry and tech is more productive, but inefficiency, poor allocation of funds and excess investment has still sapped productivity in aggregate.”

In this way, China’s technological rise is impressive and enormously wasteful. Its industrial policy has forged some highly productive technological titans, and countless zombies.

This should be a warning for those admiring Xi’s model. Beijing’s successes are also unique to its structure. The CCP’s centralised control allows it to mobilise resources at speed and scale, and drives a focus on the end goals of its industrial policy — not the means or their consequences.

“China has the wrong strategy for generating fast productivity growth,” notes Rajah. “A better one would involve liberalising markets, reforming state enterprises and strengthening rule of law.”

Indeed, enduring growth and innovation come from utilising capital, land, labour, public funds and ingenuity efficiently, not from scrambling them from one project to another. This requires both free market forces and prudent government.

After all, DeepSeek emerged from a hedge fund that was developing AI models for algorithmic trading, not government subsidies.

Beijing can build tech giants, but it is far harder to manufacture productivity growth.

The CCP should keep this in mind as it discusses its next five-year strategy at its Fourth Plenum in the coming days.

Thoughts? Rebuttals? Message me at freelunch@ft.com or on X @tejparikh90.

Food for thought

The global hunt for critical minerals is heating up. For developing nations with abundant deposits, this column argues the race can be as much a “curse” as a blessing.

Free Lunch on Sunday is edited by Harvey Nriapia