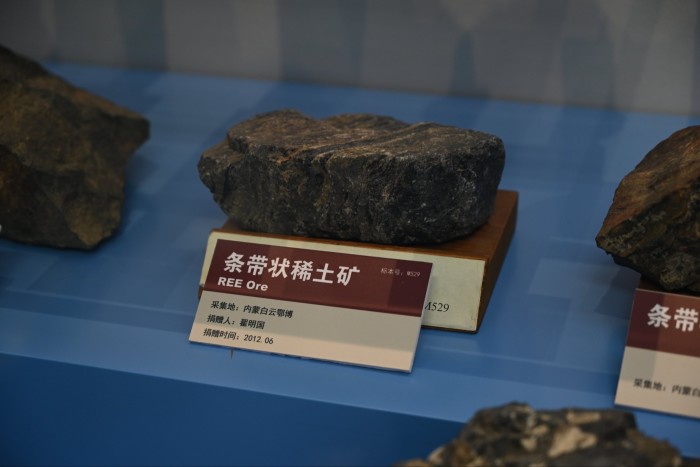

Western companies have warned that the renewed US-China dispute over rare earths materials will lead to “broken” supply chains and higher prices for chips, cars and weapons as industry executives plead for de-escalation between the two trading powers.

China first introduced rare-earth export restrictions in April in retaliation for tariffs imposed by the Trump administration, causing delays with vehicle production and forcing western companies to stockpile materials.

Last week, Beijing tightened those rules further, requiring foreign companies to get approval to export magnets that contain even trace amounts of China-sourced rare-earth materials and restricting the sharing of magnet-making expertise with foreigners.

In response, US President Donald Trump threatened to impose an additional 100 per cent tariff on imports from China ahead of a meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping this month.

“The new regulations issued by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce are expected to have far-reaching consequences for deliveries of the affected products to Germany and Europe,” said a spokesperson for German car industry group VDA.

Defence executives and other industry stakeholders said the new export controls from China could delay production of some weapon components and push up prices despite recent stockpiling efforts. Rare earths are crucial for various defence technologies including F-35 fighter jets, Tomahawk missiles, radar systems and drones.

Gracelin Baskaran, director of the critical minerals security programme at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said Beijing’s new measures would significantly hit the defence sector.

They are taking “even the most trace amounts of Chinese material out of foreign military capabilities, which is hugely penalising”, said Baskaran.

China dominates the production of rare earths, processing about 90 per cent of the world’s supply chain and over 90 per cent of magnet manufacturing. These rare-earth minerals and magnets are critical to technologies from smartphones to electric vehicles and fighter jets.

The rules make it more difficult for other countries to develop their own magnet industries by banning or restricting the export of a broad range of related technologies and processes, and limit the ability of Chinese individuals to share technical materials or information.

Carmakers have doubled or tripled their orders from German magnet maker Magnosphere since Beijing’s new measures were announced last week.

“We’re going to get it done one way or another,” said the company’s chief executive Frank Eckward.

Still, he warned of “severe problems” ahead for the global automotive industry: “It’s not just the car manufacturers but also the delivery chain to the car manufacturers is becoming broken,” he said. “They have been getting broken since the beginning of this year, but it’s going to accelerate.”

Depending on how strictly Beijing enforces the new rules, legal experts in China said it could be harder for European companies, even those based there, to collaborate and order new rare-earth magnets from Chinese groups.

The rules say Chinese rare-earth magnet makers will need an export licence before they can legally share or discuss any detailed process specifications with foreign buyers, inside or outside of China. This includes discussing design drawings and simulation data for rare-earth magnets to be sold.

A European business representative in China, who asked not to be named, said the potential for collateral damage to industries beyond the US did not appear to be “on the minds” of the officials who designed or decided to launch the latest controls.

The executive said that, given that there is a “large” backlog of export licence applications waiting for approval, a key question is how will officials in Beijing cope with the increased workload.

Jens Eskelund, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, said the organisation planned to complain to Chinese officials. “This is significant and we will raise this,” said Eskelund.

In the defence sector, US technology start-up ePropelled, which makes propulsion motors for drones, said China’s export restrictions “threaten to delay some production, possibly drive-up costs, that could potentially lead towards costly redesigns and alternate sourcing”.

The company added that it had “partnered with key companies in rare earths to limit the possible negative impact on the business”. ePropelled in August announced a joint development agreement with USA Rare Earth, which is developing a mine and a magnet-making facility, to provide sintered neo magnets for use in its motors.

ASD, Europe’s aerospace and defence trade body, said the latest export controls “underscore the urgent need for Europe to make its supply chains more resilient and reduce its critical minerals dependences”.

Large defence companies have been working on building stockpiles and securing alternative, non-Chinese, sources of supply for at least two years.

US group Northrop Grumman said it had “proactively increased [its] procurement and inventory of some minor metals and rare earth elements”.

BAE Systems, Britain’s biggest defence contractor which builds everything from submarines and fighter jets to ammunition and tanks, said the recent move “isn’t currently impacting our business”.

Western companies have been developing “mine to magnet” supply chains. In October, US magnet manufacturer Noveon Magnetics signed a memo of understanding with Australian miner Lynas Rare Earths to form a “strategic partnership aimed at establishing a scalable and domestic US supply chain” for the materials.

Still, industry watchers remain hopeful that the US and China would ultimately reach an agreement to ease the restrictions. VDA called on Brussels and Berlin to “find a viable solution quickly” with Beijing.

Baskaran at CSIS added that it was likely the new restrictions were a negotiation tactic. The fact that they would not take effect until December 1 “essentially gives you 2.5 months of a runway to negotiate, which is a considerable amount of time really”.

Additional reporting by Camilla Hodgson in London and Sebastien Ash in Frankfurt