Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Good morning. Paramount has paid $150mn for the start-up online news organisation The Free Press. What does that imply about the value of the Unhedged newsletter/podcast empire? Send your sealed bids to: unhedged@ft.com.

US regional bank mergers

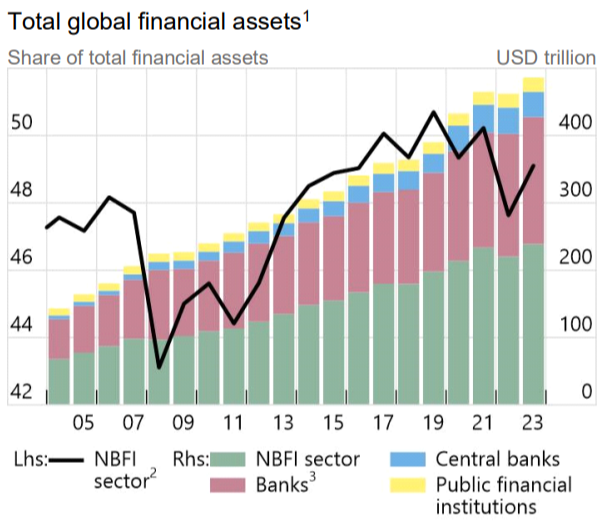

Start at the global level: banks are becoming a sideshow. Nonbank financial institutions have had more assets than banks for more than a decade, and banks continue to lose share steadily. As of the end of 2023, non-banks held almost half of the financial assets in the world, according to the Financial Stability Board. And it’s very likely that non-banks’ share has grown since then.

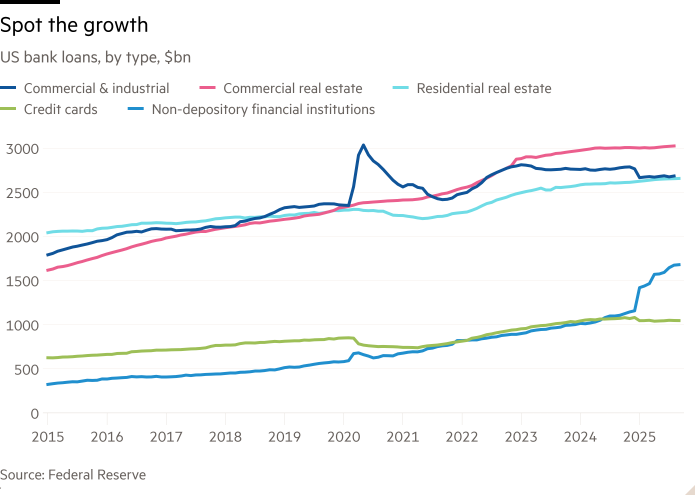

What is true globally is true in the US. Bank stocks have done pretty well in recent years as the yield curve has steepened and the economy has proven resilient. But don’t be fooled: bank loan growth has been sluggish. Here is a chart of total loans in the banking system, in five categories that together make up 85 per cent of all lending. The only bit that is growing robustly, as we have pointed out recently, is lending to non-bank financial companies.

Part of the problem for banks is that their regulatory constraints make it difficult for them to compete to be the first choice source of capital for the biggest customers. Part of the solution is to serve the non-banks, not just by lending to them but also by providing them with liquidity backstops and charging them fees for services. Higher fee revenue gives bank investors reasons to cheer, too. It earns a higher valuation than interest income in the stock market.

Liquidity provision, lending into the wider financial system, fee-based businesses: that is the future of banking, and it is a scale game. Which brings us to Monday’s welcome news, that the large regional bank Fifth Third struck a $10.9bn all-stock deal to buy its peer Comerica, creating the ninth largest US bank by assets.

Of course, there are tactical reasons for the deal: a better mix of business and retail lending, a shift to higher-growth regions for the buyer, and so on. But the strategic context is simply size, which brings with it the ability to compete for fee revenue from big, sophisticated clients and a lower cost of capital. JPMorgan Chase, the biggest US bank, makes half its revenue from fees and half from interest. At Fifth Third and Comerica, only a third comes from fees. Comerica’s cost of interest-bearing liabilities is more than a percentage point higher than its biggest peers’.

Nobody is suggesting that the US become Canada, where a few banks dominate. But if the big regionals (there are dozens with assets over $100bn) consolidate to a scale that can challenge JPMorgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citigroup, that would make the banking industry more competitive and might just make the banking system more transparent and resilient. So: hurrah for bank mergers.

(Armstrong)

Sanaenomics and the Yen

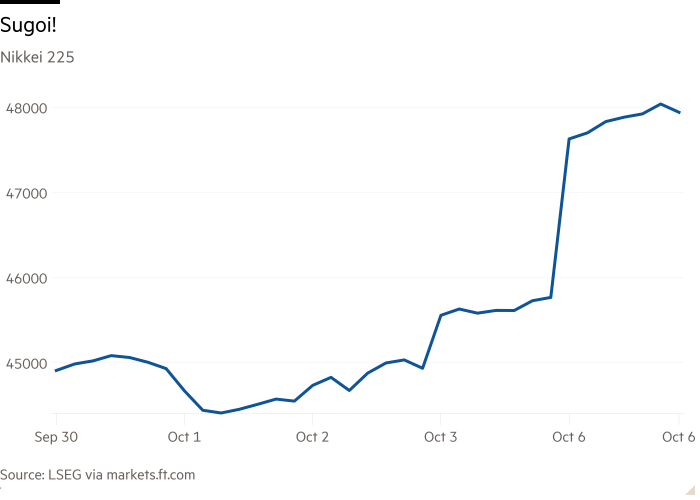

Sanae Takaichi is the presumptive prime minister of Japan, so “Sanaenomics” is centre stage. What does that mean for the Japanese markets? We had some clues on Monday. The Nikkei 225 jumped nearly 5 per cent:

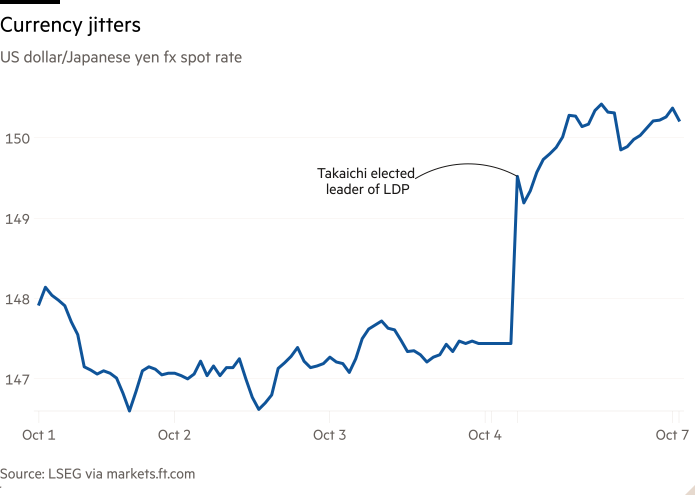

The yen weakened about 2 per cent against the dollar:

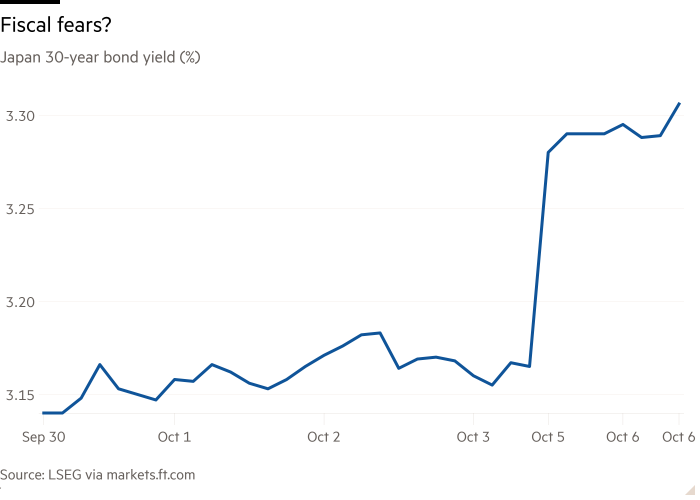

And long-dated bond yields sold off sharply:

Sanaenomics is not far from Abenomics. It, too, calls for big fiscal stimulus, tax cuts and more interventionist monetary policy to fuel economic growth. But this time around, Japan’s economy has changed. The biggest change is in inflation, which is running above the Bank of Japan’s target 2 per cent rate.

For British readers, the combination of big fiscal stimulus and looser monetary policy amid high inflation might bring unpleasant flashbacks to Liz Truss. But Kristina Hooper of Man Group told Unhedged that “of all the countries that are seeing higher inflation, it is most welcome in Japan. This is what many policymakers had hoped for a long time.”

Hooper also points out that while Japan’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio is over 200 per cent, the figure is half of that on a net level — similar to the US’s levels — because the BoJ owns so much of Japan’s government debt. This reduces the bond market risks of loose fiscal policy.

The real risk is to the yen. Tim Baker of Deutsche Bank said he was turning from bullish to neutral on the yen in the aftermath of Takaichi’s party leadership win, expecting weakness in the currency during the near-term:

[Takaichi’s] stance on addressing inflation still looks different from traditional policy prescriptions. We note she has: (1) argued that inflation in Japan is more cost-push than demand-pull; (2) emphasised fiscal relief over monetary policy to address price pressures and not ruled out cuts to the consumption tax; (3) noted that the government and BoJ should work closely together . . .

Takaichi is correct that the yen, rather than demand-driven inflation, has helped lead the economy out of disinflation, and her fiscal policies appear to be aimed at supporting consumers who have suffered under high import prices. But if investors become concerned about looser fiscal policy, and the BoJ does not resume rate increases, a still weaker yen seems all but inevitable.

There is also the possibility Takaichi cannot get her policies past the opposition. Rory Green of TS Lombard outlines the obstacles:

A policy mix of stimulus, state intervention and immigration antipathy will be challenging to implement against a backdrop of sharply rising yields, sticky inflation, structural labour shortages and deep LDP unpopularity . . . Don’t expect Abenomics 2.0.

(Kim)

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.