Greetings. Last week, I dissected my interview with Michael Pettis on China’s role in the global macroeconomy and, in particular, the challenges its surplus poses to others. This question is a staple of global economic policy discussion. While people can and do disagree on what to do about “global imbalances” and who is to blame for them, it is usually taken as axiomatic that they are a problem that we would be better off without.

Today, I want to share some heretical thoughts questioning that premise. I don’t disagree with the view that China should raise domestic consumption spending and redirect the amount of savings it exports abroad. That would undoubtedly be in China’s interest: the country has a lot of poor people who are better recipients of Chinese surpluses than US consumers. But Chinese authorities’ willingness to do this is in doubt, and policy is erratic, seemingly boosting domestic demand with one hand while shrinking it with the other.

So, suppose China maintains domestic policies that produce surpluses because it doesn’t want or can’t find the policy levers to rebalance its macroeconomy. The standard analysis is that this undermines growth and, in particular, manufacturing in other economies. I want to give some reasons for thinking China’s surplus need not be a bad thing, but could be a force for good. Share your reactions: freelunch@ft.com.

To say that China’s surplus could be a good thing is to reject that this amounts to a “beggar-thy-neighbour” policy. A reason for doing so is that we know of historical examples where large export surpluses and import deficits contributed to stronger growth and even manufacturing expansion in both the surplus and the deficit economies.

The most important historical example is, of course, the years after the second world war. Back then, the US was the big net exporter of goods and capital, “forcing” its surpluses on a defenceless world. Or, put differently, it manufactured and shipped products that allowed war-torn Europe to consume and invest more than it otherwise could have.

As the graph above shows, in the immediate postwar years, the US ran external surpluses that usually exceeded 2 per cent of its GDP, sometimes by a lot. This is comparable to China today (and remember that the US was a much larger share of the world economy back then, so, if anything, its surplus was “worse” than China’s today).

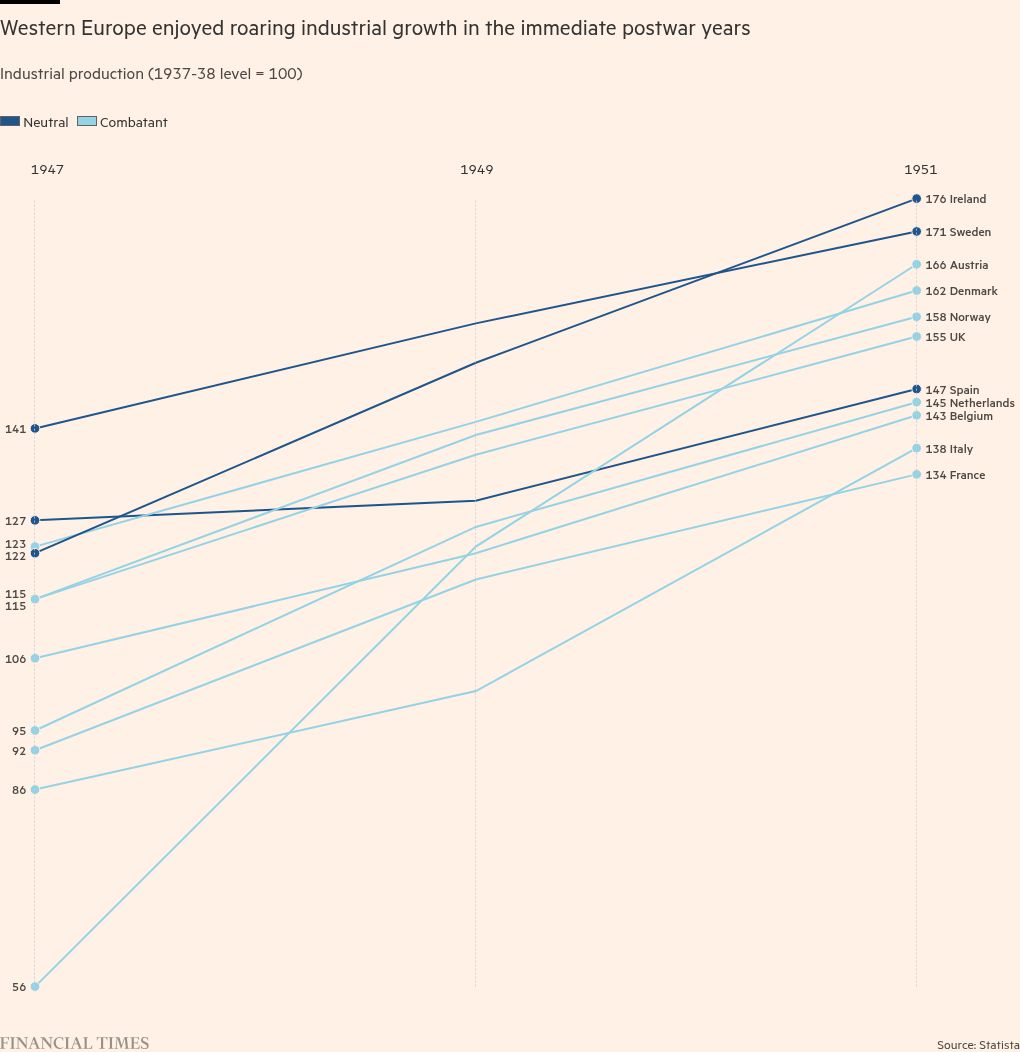

By a logic that is commonly heard, this American “overcapacity” must have undermined manufacturing elsewhere and, in particular, in deficit economies. But the opposite was the case. Industrial production in western Europe grew strongly after the war, as the chart below shows. (The same is true for agricultural output.)

After a short demobilisation-induced pause, US industry also rebounded from spring 1946 onward.

There are obviously a lot of differences between the immediate postwar economy and today’s. The point is simply how the postwar experience demonstrates that large external balances are compatible with strong manufacturing growth in both surplus and deficit economies at the same time. But that possibility is ruled out by much of the discussion of surpluses and deficits today.

If benign “global imbalances” have existed in the past, could similarly benign ones exist today, and what would it take to achieve them? In particular, can China’s surplus be as benign for the world (and itself) as the US’s was in the late 1940s? And if not, why not — what are the key differences from the postwar years that mean what has happened before cannot happen again?

Answering those questions seems to me as important as considering how to reduce today’s external balances. In fact, it is more important, since reducing them may be a worse policy than making them work for us, as they did in the late 1940s.

It was US policy to relieve European “dollar shortage”, the term for the old world’s impaired capacity to pay for imports through sufficient exports (or foreign investment earnings; vast European-owned assets overseas had been liquidated during the war). In other words, the US set out to boost Europe’s purchasing power through grants and loans — a “dollar surplus recycling mechanism” in the jargon. Look through the financial intermediation, and it boils down to the US sending some of its surplus production across the Atlantic for free or on credit.

The basic answer as to why both surplus America and deficit Europe could thrive and boost their industrial production is that US surplus earnings were used for productive investments in Europe, rebuilding and modernising infrastructure and factories destroyed in the war. (It is fascinating to read the 1947 IMF report on this today.) There were perhaps three main factors behind this.

The first was simply the fact of loosening the economic constraints. The flow of money and goods meant it was easier to finance investments. It also made it easier for cash-strapped European governments to run stable fiscal and monetary policies.

The second and third factors were institutional features of the most celebrated part of America’s surplus restructuring mechanism: the Marshall Plan. The US-led planning structures to which Marshall aid money was tied required, on the one hand, an integration of the national economies of the recipient countries, and, on the other, involved a controlled selection of what was financed. An industrial policy, in other words, that by all accounts was successful enough to produce a high growth rate. And that high growth rate, in turn, helped sustain demand for US manufacturing production that could also continue to grow.

Could there be an equivalent recycling mechanism for China’s surplus today? Perhaps not with the US, and not just because its political leaders seem to want zero net imports. The US is, after all, the world’s leading economy, so one might think it would be harder to find productive manufacturing investments there compared with war-torn Europe. Yet it is not entirely clear that this is the case: a counter-example is the artificial intelligence-related data centre and chips boom.

But could China’s surplus be productively directed elsewhere? This is essentially a question of whether Chinese “overcapacity” really is just that, or whether there are places that could put that capacity to use in order to boost their own growth, as Europe once did with US “overcapacity”. My take is that until every country in the world has adequate infrastructure, every business has plentiful access to clean energy and every household enjoys all the basic durable goods, it is obscene to talk of “too much” capacity. What we should be talking about is what prevents importing countries from absorbing much-needed goods and capital productively, or, in other words, how to establish a functioning surplus recycling mechanism for China.

There have been times when Beijing seems to have got this. Some of the infrastructure lending in the Belt and Road Initiative can be seen in that vein. But China just as often looks like it is seeking other solutions to the surplus issue, such as by limiting exports or trying to rein in industrial capacity (see Matthew Klein’s discussion of “anti-involution”). What is clear is that China has failed to persuade trade partners that its surpluses are good for their growth, largely because it has not shown enough interest in making those surpluses contribute to the importers’ growth potential.

Recently, China’s diplomats have been emphasising the country’s role in the second world war, 80 years after its conclusion. The suggestion is that the country can make a claim to be a co-equal creator of the postwar international order. But that order was built by the economic policies of the late 1940s, too. To live up to such claims, Beijing’s economic decision makers should think hard about the lessons of the Marshall Plan and what a productive surplus recycling mechanism would mean today.

Postscript: I have said little about contemporary Europe. But there are many things to say. The first is that the EU manages to complain about Chinese “overcapacity” and surpluses just like the US, while being in exactly the same macroeconomic position as China of running a large surplus with the rest of the world. It makes no sense, except as simple rivalry in third-country export markets, to complain that China is doing what you yourself are guilty of. The second is that Europe should not maintain its surplus model no matter what China does; it has a desperate need for capital investments at home and should be funding those, not other economies.

The third point is that Europe offers not just the example of the Marshall Plan, but several other cases of surplus recycling challenges that cast light on today’s global issues. A recent, discouraging example was when surpluses in the EU’s industrial core funded wasted spending booms on the Eurozone’s periphery in the mid-2000s. But in the decade before that, the EU core put surpluses to use in newly free eastern Europe, with manufacturing benefiting in both the source and recipient countries from huge cross-border industrial capital investments. The absorption of Poland and neighbouring economies into a manufacturing supply chain with Germany at its core was another great example of a benign surplus recycling mechanism. These are historical lessons for everyone to ponder.

Other readables

● The FT investigates the Russian spy ship that keeps Nato commanders awake at night.

● Chris Giles dissects the economic arguments of Stephen Miran, Donald Trump’s new man on the Federal Reserve’s board of governors.

● The New York Times offers steady updates on the US federal government shutdown.