Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Australia has embarked on a A$25bn defence spending frenzy, ordering fleets of autonomous aircraft and submarines, Japanese-designed frigates and transforming a key shipyard in what amounts to the country’s biggest military overhaul since the second world war.

The country’s greatest advantage in defence has long been its distance from potential adversaries. But Chinese live-fire naval exercises a few hundred nautical miles off its eastern coast this year made clear it needed to be better prepared.

“Australia faces the most complex, in some ways, the most threatening strategic landscape that we have had since the end of the second world war,” defence minister Richard Marles said in August.

US President Donald Trump has also been putting pressure on global allies, including Australia, to rapidly raise defence spending. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is set to meet Trump on October 20, when the two are expected to discuss defence spending and security in the Indo-Pacific region.

The Australian spending surge follows a landmark review that found the emergence of “major power strategic competition” in the Pacific, marked by an increasingly “ambitious” China, had fundamentally changed the country’s defence needs. It also called for Australia to reduce reliance on its allies for protection.

“The urgencies are clear,” Kurt Campbell, the former US deputy secretary of state, told the National Press Club in Canberra.

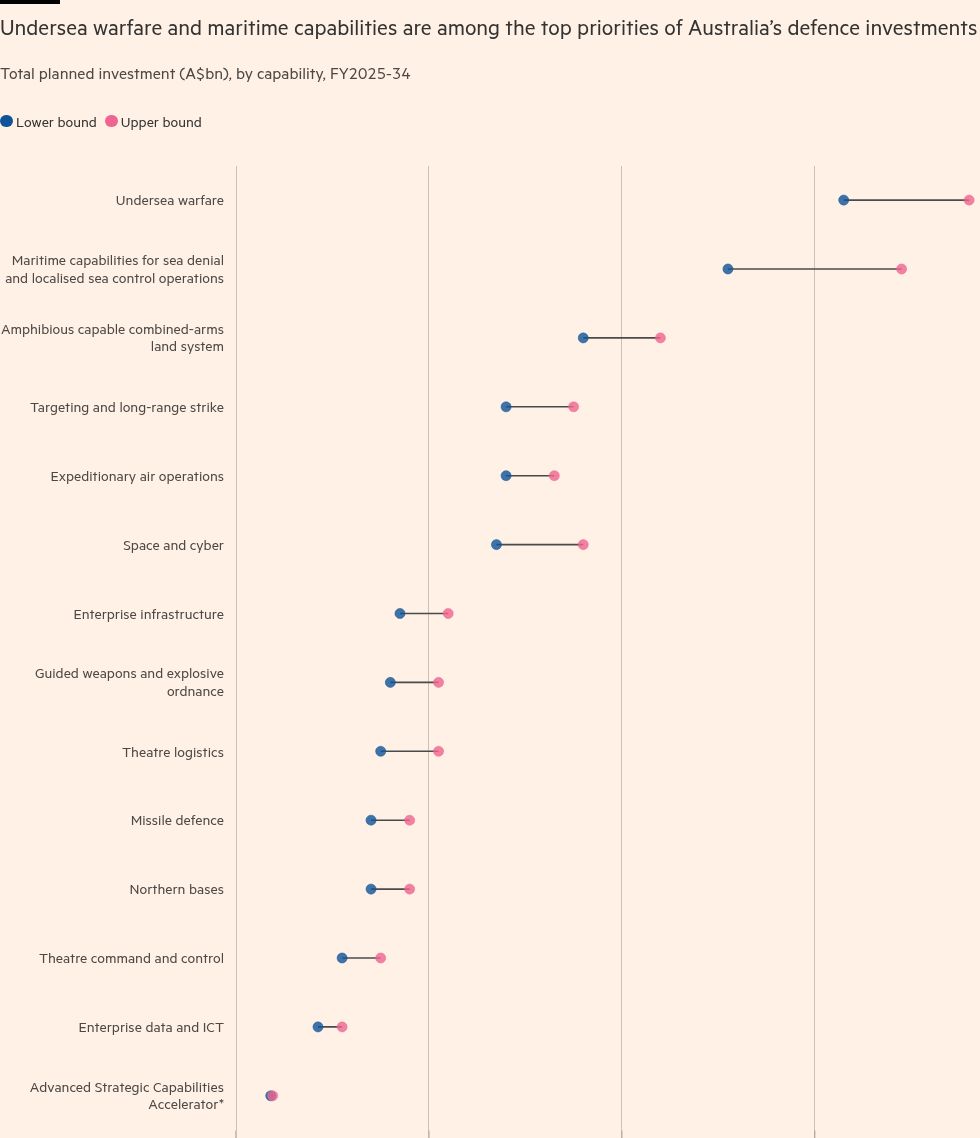

Australia has named Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries as preferred bidder on a A$10bn contract to build up to 11 Mogami frigates, part of a A$55bn investment in overhauling the country’s surface fleet that also includes a contract with the UK’s BAE Systems to build Hunter Class frigates in Adelaide.

Last month, it also committed A$12bn to the initial phase of an upgrade to the Henderson shipyard south of Perth to revamp a facility that previously made superyachts to turn out the Japanese-designed frigates and service nuclear-powered submarines.

In the skies, Australia is testing MQ-28A “Ghost Bat” drones, developed under a A$1bn contract with Boeing. The “loyal wingman” drones, which will accompany crewed aircraft, are the first military aircraft designed in the country in more than 50 years, and are part of a A$4.3bn investment in aerial drone capabilities.

Canberra has also locked in a A$1.7bn contract with US defence tech group Anduril to produce a fleet of autonomous underwater vessels, known as “Ghost Sharks”, which will be made in Sydney.

Marles said the vessels could be harnessed for intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and strike missions. “This is a lethal capability,” he said. “This is the world’s leading capability in terms of a long-range, uncrewed autonomous underwater system.”

Leidos, another US defence company, was last month awarded a A$46mn deal to provide operations systems to a A$1.3bn, decade-long anti-drone programme.

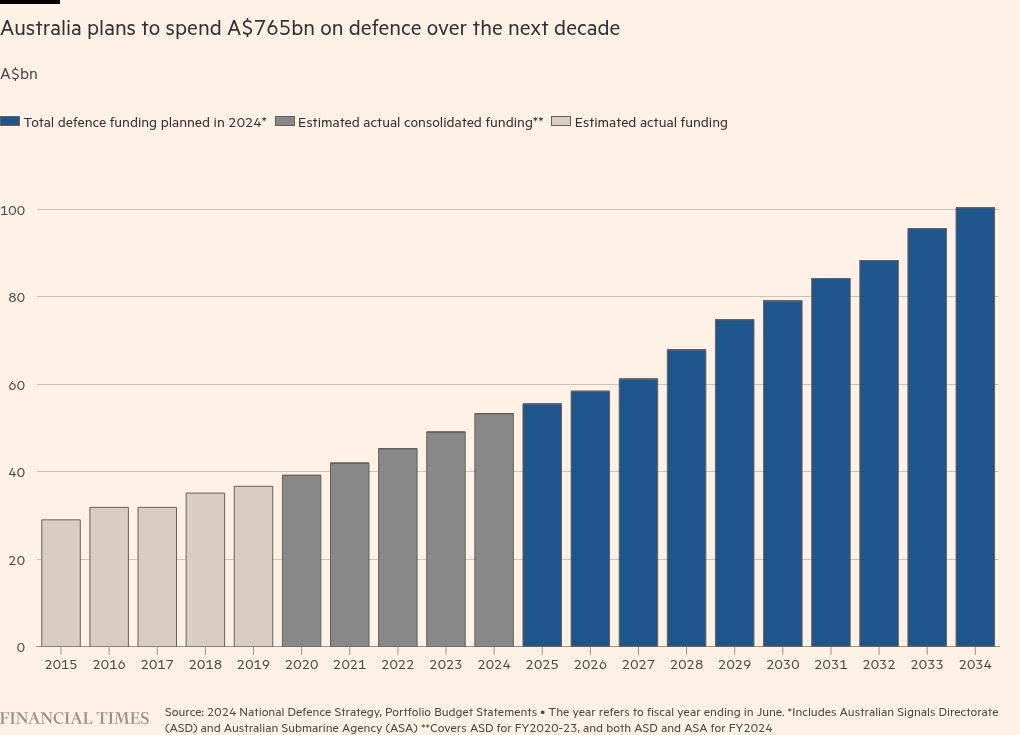

Luke Yeaman, chief economist at Commonwealth Bank, said defence spending would rise to 2.25 per cent of GDP by 2028, from around 2 per cent currently. He forecast that figure would rise to 3 per cent within a decade as the trilateral Aukus security pact with the US and UK and other expenditures came online.

The sheer scale of Aukus — under which Australia will acquire nuclear-powered submarines for the first time — has cast a pall over the defence budget. Yeaman estimated the cost of the deal at between A$268bn and A$368bn by 2050. Albanese has said his government will increase defence expenditure by A$70bn in the coming years.

But some say Canberra is still not spending enough.

“Defence spending is still lax,” said Steve Baxter, founder of defence investment fund Beaten Zone Venture Partners, who said Australia packed the “sense of urgency” of US defence planning. “The strategy is right but it’s not been funded,” he added.

While the bulk of the committed spending has been on submarines and frigates that are vulnerable in modern warfare, Sam Roggeveen, director of the Lowy Institute’s International Security Program, said the government should be focused on shoring up the country’s north.

The defence build-up also highlights Australia’s complicated relationship with China, which is the country’s largest trading partner. Restoring economic ties with Beijing was one of the biggest accomplishments of Albanese’s first term.

“The government is torn between different political goals — the relationship with China but also deterring China,” said Andrew Carr, senior lecturer in the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at The Australian National University.

More broadly, Carr said, the government has failed to explain to the public what the new “national defence” posture would mean.

Unlike Japan and Taiwan, Australia was not accustomed to the idea of hostilities close to its shores, he said.

“There’s no discussion on trade-offs between guns and butter or public support for the costs to society if war breaks out,” he said.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko in Hong Kong