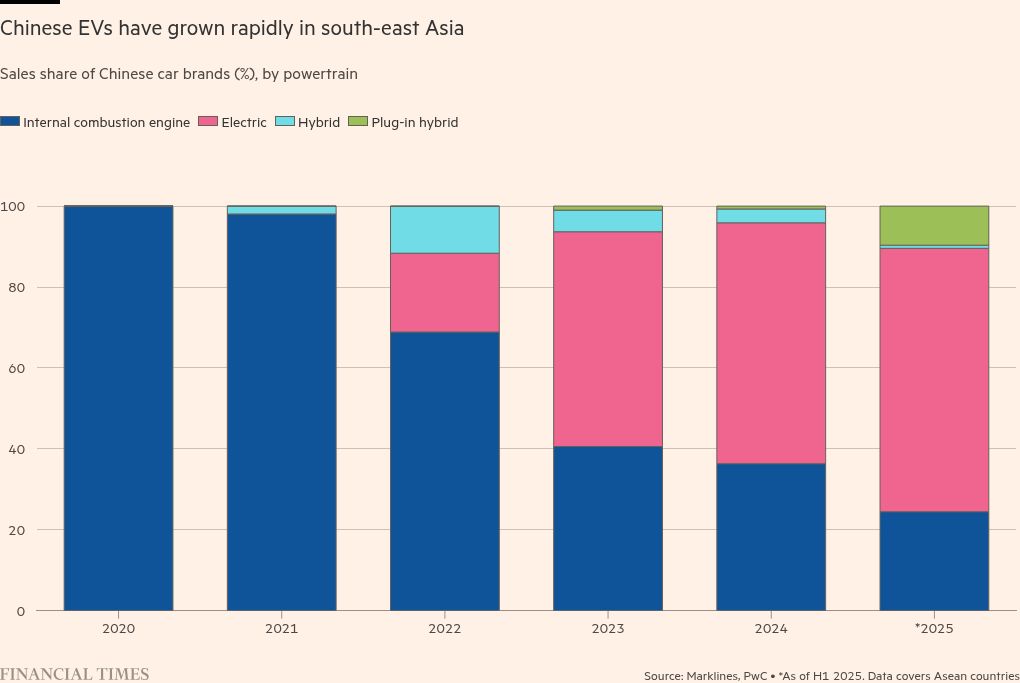

Surging sales of affordable Chinese electric cars are breaking Japanese automakers’ decades-long grip on south-east Asia, foreshadowing disruption across other regional vehicle markets.

The market share of Japan’s producers, led by Toyota, Honda and Nissan, has fallen to 62 per cent of car sales in south-east Asia’s six biggest markets in the first half of 2025, down from an average of 77 per cent in the 2010s, according to PwC data analysis. China has increased its share from negligible volumes to more than 5 per cent of 3.3mn annual car sales in those markets.

Faced with a brutal price war at home, China’s EV makers have set their sights on exports nearby due to a region-wide free trade deal that grants their cars duty-free market access.

“Chinese EV manufacturers’ market entry has heralded the end of an era of unrivalled dominance for Japan in south-east Asia,” said Patrick Ziechmann, a Malaysia-based partner at PwC.

Ramesh Narasimhan, who formerly led Nissan in Thailand, said Japanese auto groups would keep losing market share because of China’s offensive in their “backyard”, where previously they “could do no wrong”.

“It’s easy to take pricing actions that enable you to grow your volume and market share” for the Chinese, he said. “You see that across markets in south-east Asia.”

Even so, Chinese brands may struggle to sustain growth if the region’s EV subsidies are pared back, governments demand local production and electricity infrastructure constraints become barriers.

In Indonesia, the region’s largest consumer market with a population of around 280mn, Chinese car sales are growing exponentially, even as total sales slide due to economic challenges.

Japanese brands remain market leaders, but sales are slipping by the month. Toyota’s sales of cars and trucks fell 12 per cent between January and August this year to 161,079 units in Indonesia, while those of China’s BYD tripled to 18,989 units.

The key to Chinese companies’ success is affordable battery EVs. Prices of Chinese cars in Indonesia start as low as Rp200mn ($12,000).

“Price is the . . . decisive factor,” said Jongkie Sugiarto, vice chair of the Association of Indonesian Automotive Industries. “The Japanese have to do something, otherwise they are going to lose more and more of the market share.”

There are 15 Chinese brands in the Indonesian market, and five more are expected to launch soon, Jongkie said. At least three of those companies have set up manufacturing facilities in Indonesia, while the rest assemble cars in the country through local partners, including Jongkie’s company, PT Handal Indonesia Motor.

Chinese companies have also benefited from incentives offered by the Indonesian government, including import duty exemptions for battery electric vehicles. But those benefits will cease from next year, and automakers will be required to produce locally to receive subsidies.

Subsidy eligibility requirements have already proven challenging for smaller Chinese automakers. Neta, a Chinese EV brand, was this year warned by Thailand’s finance ministry that it might have to return subsidies if it fails to build at least three cars locally for every two imported by the end of the year.

In Singapore, China’s takeover has been even more stark. BYD became the top-selling car brand this year, overtaking long-term market leader Toyota, which, as recently as 2023, accounted for 25 per cent of sales.

Government efforts to improve electric vehicle infrastructure, combined with several Chinese brands entering the market, have encouraged Singaporeans to switch to EVs. In BYD’s case, it has targeted the market with flashy showrooms in malls and in the city centre, as well as tie-ups with bars and restaurants.

“There is a bit of a market shift in Singapore right now,” said Adam Mirza, managing director at Prestige Auto Export, which deals in Japanese cars. Japanese brands “have accepted the fact that they can’t compete on EVs with the Chinese brands.”

Chinese EV makers are also hoping to leverage their leadership in vehicle software technology, which Japanese legacy carmakers have been slow to develop. Chinese start-up Xpeng started shipping the X9 model, which includes smartphone-controlled parking, to the region in February.

“We see south-east Asia as a market full of potential,” said Xpeng president Brian Gu in April.

Jessada Thongpak, associate director for Asean at S&P Global Mobility, said China’s south-east Asia advance was likely to be replicated elsewhere.

“We’re much more advanced. In Latin America, it’s the early adoption stage. We’re still in early adoption here but it’s resilient uptake,” he said, predicting Chinese companies would account for 20 per cent of Thailand’s car sales by 2032.

As a regional manufacturing hub, Thailand is also being transformed. Subaru shut down its plant last year, while Suzuki plans to close its facilities by the end of 2025. By contrast, BYD last month exported its first vehicle from Thailand to Europe.

Liu Xueliang, BYD’s Asia-Pacific sales director, said Japanese carmakers historically have helped boost the region’s economic growth. “But we’ll let consumers decide who the ultimate winners are,” he added.