Hiromi Matsukawa’s design revelation came eight years ago, when a worker from one of Japan’s pachinko gaming parlours interviewed for a job at her family business.

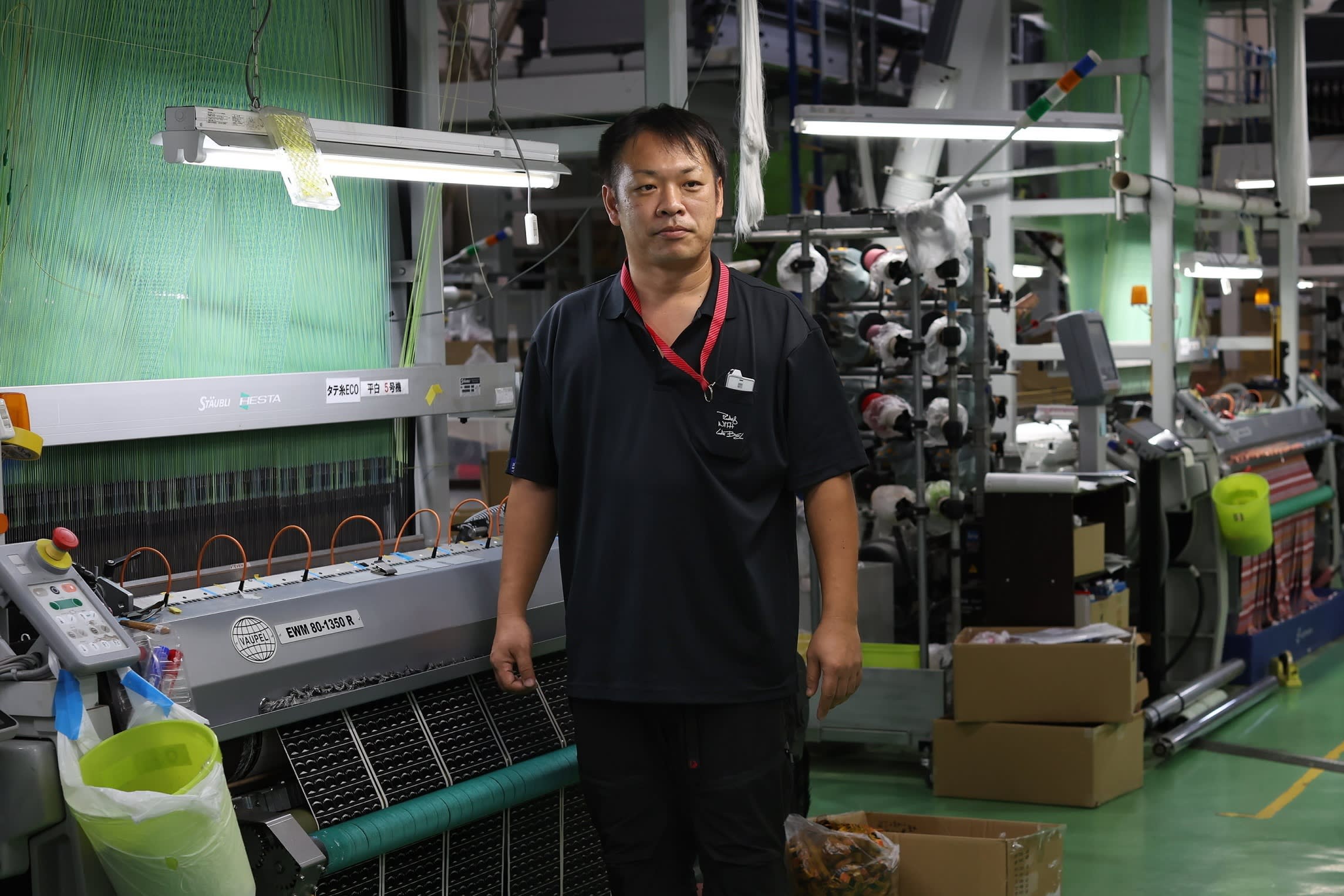

Ashamed of making a living off gamblers, Makoto Monzen said he wanted to work somewhere that would make his newborn daughter proud. Matsukawa took in the dated facilities at the woven label-making company she ran with her husband in Fukui prefecture, and realised their appearance offered little to take pride in.

The encounter prompted the 66-year-old to invest ¥460mn ($3.1mn) in a new office for the company’s 95 employees. It was a huge sum for the family-owned Matsukawa Rapyarn. But in the most labour-constrained prefecture of the world’s most aged country, this was no run-of-the-mill renovation. The sleek wooden furniture, café canteen and relaxation areas represented a decisive move in a fight to secure the 100-year-old textile manufacturer’s survival.

Matsukawa Rapyarn is one of thousands of Japanese companies pouring money into office makeovers, as the battle to attract workers becomes fiercer than ever. The resulting boom for the furniture and refurbishment trade has defied fears that a shrinking domestic market and intensifying global competition would throttle modernisation.

Sales of office furniture and equipment in Japan were ¥862bn in the year to March, 14 per cent higher than four years earlier — significant growth in an overall population losing more than 600,000 people every year.

The office renewal has transformed a Tokyo Stock Exchange backwater, creating a windfall for Japan’s three big business furniture suppliers. Their share prices have at least doubled since the start of 2022, as 30 years of price wars have finally ceased.

At Matsukawa Rapyarn, the reinvestment was a game-changer. With 1.87 openings for every jobseeker in Fukui, compared with a national average of 1.25, the company had for years struggled to fill staffing gaps. Its new office, where employees from sales to design now work in buzzy surroundings and factory workers come to relax on their breaks, proved a huge draw. Applications rose three-fold and unsolicited enquiries from job hunters came in.

“We wanted to make an environment where they’d feel proud to work,” Matsukawa said. “It’s had a huge impact on recruitment — far more than we ever thought it would.”

Refurbishment is one of many creative responses to Japan’s labour shortages and sticky inflation. Employers and regional governments are repaying student loans, subsidising apartments or shortening the working week to attract staff. Refreshing sites dating back to the Shōwa era — the period between 1926 and 1989 when much of Japan’s workplace infrastructure sprung up — offers businesses another chance to set themselves apart without the recurring cost of wage increases.

The trend of thoughtful office investment also indicates a shift in Japan’s corporate culture. The era of Japan’s salaryman, the single-company lifetime loyalist that drove the nation’s postwar economic growth, is coming to an end. Employees’ power to choose where they work is forcing companies to fight to attract them, propelling once-unthinkable shifts in management behaviour.

“The origins of Japan as a nation are respecting the organisation or group over the individual. The company comes first and the individual after,” said Masayuki Nakamura, president of Okamura, one of Japan’s big office suppliers. “That way of thinking has begun to collapse.”

The focus on employees is reflected in the work of Okamura, which like others in the sector covers the whole redesign process, from architecture to furnishings. Its designs encourage a dynamic, collective approach to work with spaces where departments can mix, convivial curved meeting tables and quiet areas. It offers comfortable wooden furnishings and touches, such as decoration referencing the company history or industry.

Hiroshi Ono, a professor at Hitotsubashi University, said Japan had been slower to modernise its workplaces than countries such as the US — but its transformation was still decisive. “In the Shōwa period, companies had this attitude that you’re lucky working for us. That has turned around. The companies have to make themselves the chosen ones.”

The rise in employee power can also be traced back to Covid-19. Although less marked than in other countries, the shift to working from home accelerated pro-worker reforms advocated by late prime minister Shinzo Abe.

Koji Minato, president of office furniture supplier Itoki, said the first wave of the office renewal boom immediately after the pandemic centred around Tokyo, and was about incentivising employees back to the office. Labour shortages triggered the current second wave, and he expected a third phase linking office design to data from devices monitoring employee wellbeing and productivity. For example, lighting that automatically reacts to improve mood or concentration or even trackers that show where employees are in the office.

“With Japan’s population declining, if you don’t build a stylish, appealing office, people simply won’t come and work for you,” Minato said. “Those who struggle the most with this hiring challenge are not the big companies in Tokyo but small to mid-sized regional companies.”

Yoshinori Saito, who advises SMEs at the Fukui Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said few were as brave as Matsukawa Rapyarn. “Many don’t have the ability to invest.” Instead, “SMEs are hiking wages — not because their business performance is going well but as a defensive measure to stop employees from leaving”.

Akihisa Matsukawa, Hiromi’s son who is the fourth-generation boss of Matsukawa Rapyarn, believes men are still likely to chase higher salaries regardless of the work environment. But he thinks the draw of a pleasant work environment, and the brand and social media cachet it brings, is worth the investment for his majority-female company, which has seen the number of people leave fall from 10-12 to five annually. “More people were quitting before due to a mismatch in expectations.”

Fukui prefecture is itself looking to put government heft behind the modernisation of outdated workplaces to stem the outflow of young people leaving for bigger cities. It signed contracts to secure land for two industrial parks to which it will invite companies to build new workplaces.

“It may sound like a strange thing to do when we don’t have enough people but it’s a big factor for getting young people to move back here,” said Shigeru Saigyo, Fukui city mayor.

Japan’s office furniture suppliers believe they are uniquely positioned to export knowhow as other nations grow old. “I think Japan is advanced on this trend and it’s going to come to the US, Europe and Asia,” said Hidekuni Kuroda, president of Kokuyo, the country’s third big office supplier. The company estimates it has more than twice the office renewal work it had before the pandemic; Kuroda said much of this was down to young people’s desire to feel career achievement, what he dubbed “lifework” over “ricework”.

Even so, the office renewal boom still faces a threat as artificial intelligence renders more white-collar jobs obsolete. Furniture executives argue AI could trigger a new wave of redesigns, just as computer technology meant steel cabinets made way for flat screens. But the fear that the bubble may burst is real.

“The biggest risk and chance is AI,” said Kuroda. “If it becomes common that there’s no need to invest in a physical office, then the current boom will end. If white-collar workers aren’t needed, then that would be the worst case.”