One of the few things that Americans have been politically united on in recent years is the need to get tougher on China, economically and politically. So, it’s quite interesting that over the past couple of weeks, we’ve seen a real pivot on how the administration seems to be dealing with Beijing.

First, there was US defence secretary Pete Hegseth’s comments about not seeking conflict with China, and the gentler than usual language of diplomacy used by Secretary of State Marco Rubio in talks with Chinese counterparts in early September. This followed a leaked Pentagon memo proposing that the US shift from its focus on China (and by proxy, Taiwan) and focus on regional issues, and homeland security. This represents a significant shift away from America’s multiyear “pivot to Asia”, which began under the Obama administration, in which the US was supposed to focus itself on the Pacific and US-China relations, away from the Middle East and its conflicts. It also represents a big shift from what the Trump administration has been messaging throughout both its first and second term, which is that China is the great enemy, and that the US must prepare itself for conflict, both cold and potentially hot.

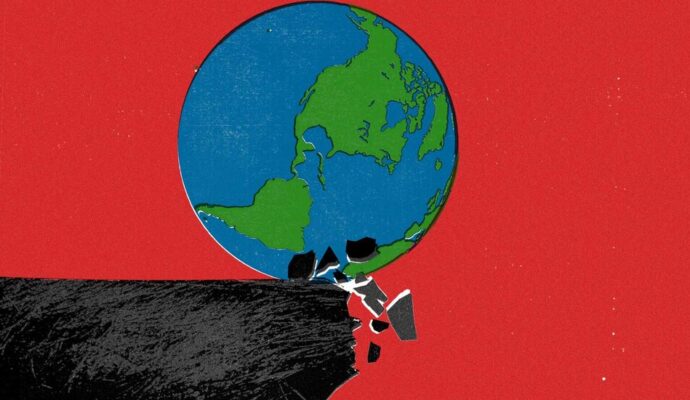

The defence department memo was apparently drafted in part by Elbridge Colby, who had previously advocated for the pivot to Asia, but is now pushing a “Monroe doctrine”- style focus on maintaining order in America’s own backyard. The question, of course, is why the shift? While some reporting has suggested that America and this White House in particular regards allies and international conflicts as difficult and constraining, there’s also a deeper truth, which I’ve touched on with many former and some current administration officials — the US simply doesn’t have enough military capacity to protect the world anymore.

While the Biden administration always signalled its willingness to defend Taiwan, and with it the idea of liberal democracy in Asia, should China attack, the Trump administration seems interested in Taiwan mainly for its semiconductor industry. My sense is that once there is a more complete revitalisation of the chip industry at home, this White House wouldn’t care much about protecting Taiwan.

That’s a position that, quite frankly, many Americans support. I like to think of myself as a supporter of liberal democracy, but in 2023, I wrote a rather controversial Swamp Note questioning whether US protection of Taiwan against a Chinese invasion was either (a) militarily doable, or (b) politically feasible. I felt it was important to get real about whether protecting a tiny island directly within China’s orbit is the best use of US resources, politically, economically, and militarily. I’m still not completely sure of the answer.

What I do think is that we are moving to a more regional and less global world. I think that the US, China (and its partners), and Europe are existing in increasingly separate orbits. And that’s both an opportunity and a challenge. As my last book laid out, I think that there are good economic reasons to support regionalisation, but there are also big questions about whether Europe in particular can survive the political pincher position of sitting between China and the US, without its own tech giants, stronger defence posture, or more unified political economy.

There are also big risks to US isolationism — although it’s not a historical anomaly. My respondent today is the FT’s US opinion editor Jonathan Derbyshire. Jonathan, my question to you is this: what do you think of a modern Monroe Doctrine? What would be the risks, and the potential upside, to any such shift?

Recommended reading

I thought Bret Stephens’ column on Charlie Kirk, and why his style of argument was good for the TikTok generation, but not great for generating real intellectual progress, was spot on. Just as an aside, I’ve always thought the British were much better at argument than Americans. We Americans all too often want to be liked more than we want to be respected, which is the enemy of smart debate.

On that note, my London-based colleague Robert Shrimsley is completely right that no one has a right to not be offended, and Republicans are being incredibly hypocritical on free speech issues at the moment.

That said, for balance, it’s also worth reading the Wall Street Journal’s Barton Swaim on the left’s own hypocrisies.

From the Washington Post, a smart and concerning read about Jimmy Kimmel and what this signals about concentrated power.

Finally, given where we seem to be, I am just starting, and loving, The Revolution to Come: A History of an Idea from Thucydides to Lenin, by Stanford professor Dan Edelstein. I love this kind of deep, ideas-driven history that tells us something important about now. I suspect I’ll be quoting him in a column soon.

Jonathan Derbyshire replies

Hi Rana. It’s obviously a fool’s errand to try to infer any kind of coherent and properly worked out foreign policy doctrine from the utterances of the president himself — beyond, that is, his viscerally held belief that international relations is a sort of Hobbesian contest in which the strong will always prevail over the weak.

But I think you’re right to suggest that we can discern from the things others in the administration have been saying the outlines of what some have taken to calling the “Donroe Doctrine” — a 21st-century version of 19th-century President James Monroe’s dictum that all and any interference in the American hemisphere by other great powers should be treated as an “unfriendly disposition towards the United States”.

Our colleague Ed Luce wrote a Swamp Note about the emergent Donroe Doctrine back in January that I think is worth revisiting. It’s the exclusion of China from the western hemisphere, Ed argued, that provides the rationale for this homage to Monroe. I think Ed was right — just look at the numbers here.

China’s presence in the western hemisphere — in Latin America in particular — is primarily economic rather than military, although Beijing has strengthened its miliary ties with countries in the region, notably Venezuela.

In the economic sphere, China is both Latin America’s leading trading partner, surpassing the US and EU, and a major investor in infrastructure projects in the region through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Take Peru, for example. According to Jorge Heine, a former Chilean ambassador to China, Peru “now exports more to China than to the EU and the US combined”, while it is the recipient of large dollops of Chinese direct inward investment, notably in the megaport at Chancay, envisaged as a future “Shanghai of South America”.

In other words, China’s economic influence in the western hemisphere isn’t an incipient threat that a revamped Monroe Doctrine might hope to contain — it’s already deeply and widely implanted across the Americas, and, as Heine points out, it might already be too late to do anything about it.

Your feedback

We’d love to hear from you. You can email the team on swampnotes@ft.com, contact Rana on rana.foroohar@ft.com and Jonathan on jonathan.derbyshire@ft.com and follow them on X at @RanaForoohar and @jderbyshire. We may feature an excerpt of your response in the next newsletter