Predictions that the world will soon be awash with oil are failing to dent crude prices, with some analysts saying China’s quiet stockpiling of reserves is staving off a major market downturn.

Big banks, energy agencies and analysts are almost universally forecasting that excess supply could push global crude prices towards $50 a barrel or lower next year.

But Brent crude, the international benchmark, is still trading at about $67 a barrel, little changed on where it was in late June, while futures markets are not pointing to a coming glut.

“There is a bit of a mystery,” said Vikas Dwivedi, global energy strategist at Macquarie. “The whole marketplace is looking for enormous surpluses and yet the price isn’t buckling. Instead of $67 a barrel, why are we not looking at $47 a barrel?”

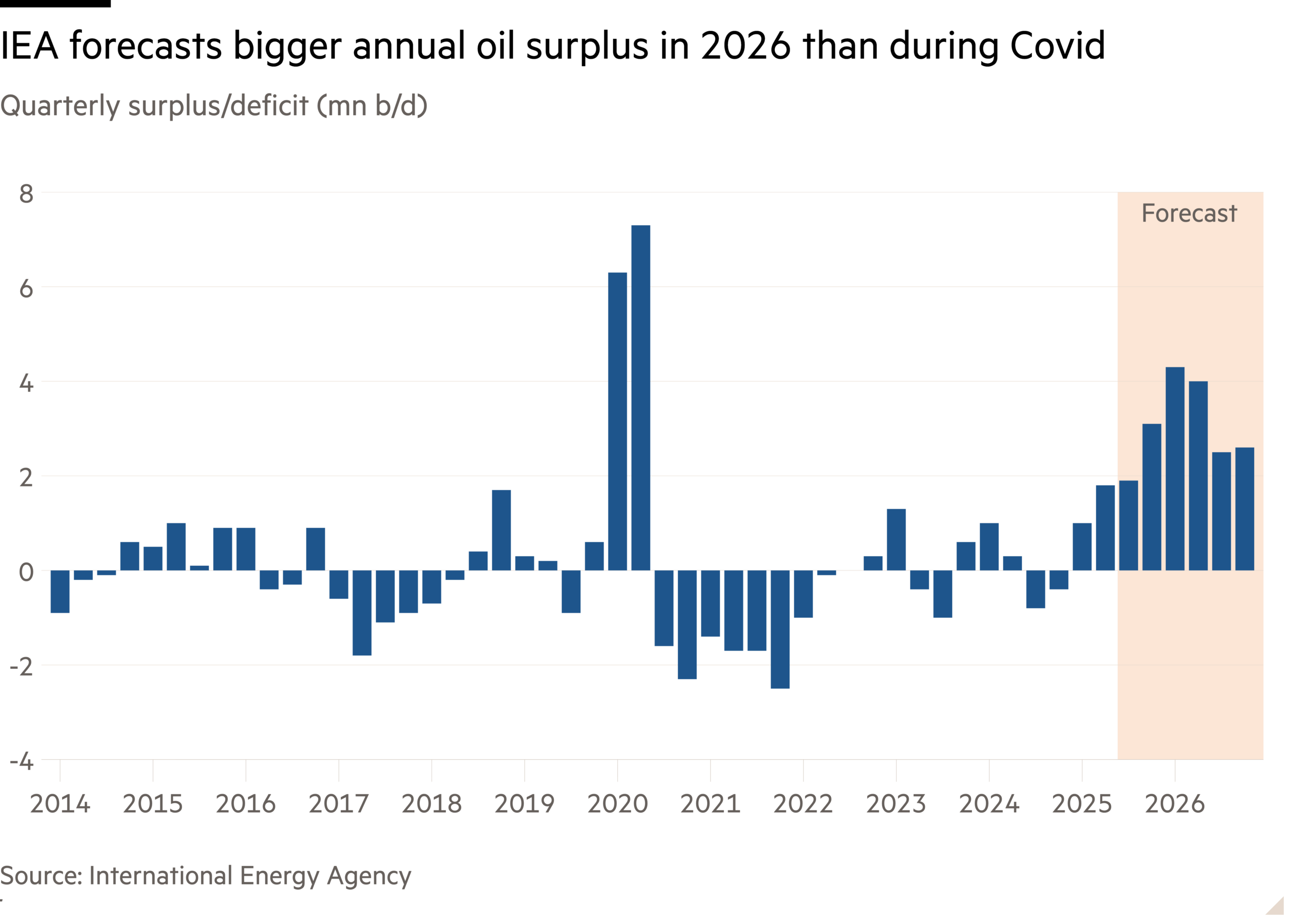

The International Energy Agency’s most recent forecast implies a record surplus of 3.3mn barrels a day in 2026. Likewise, the US Energy Information Administration last week predicted a surplus of 2.1mn b/d in the second half of this year and 1.7mn b/d next year.

The agencies are not alone. Investment bank Macquarie forecasts surpluses of about 3mn b/d in the final quarter of this year and the first quarter of next, while consultancy Rystad expects next year’s surpluses to average 2.2mn b/d.

The predictions mean that, barring changes in production or consumption, the glut next year will be bigger than the one in 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic crushed demand, prices averaged $42 a barrel and West Texas Intermediate briefly crashed into negative territory.

However, crude prices have remained resilient this year even as the Opec+ cartel has rapidly increased production. At the same time, the main benchmarks have been in so-called “backwardation”, meaning oil for immediate delivery is more expensive than oil for future delivery future. This typically signals a tight market, not an impending glut.

The disconnect can be explained in part, according to Dwivedi, by the fact that excess oil this year has been stockpiled in Asia or put in floating storage, rather than in more closely monitored storage areas such as Cushing in the US or Rotterdam in Europe.

“In order to matter, you have to see the stock builds in areas that are highly visible to the broader market and not just oil specialists,” he said.

Much of this has occurred in China, which has been aggressively buying crude for its strategic petroleum reserve. While such stockpiling elsewhere in the world would typically be viewed as a bearish signal that supply is exceeding demand, traders have treated Chinese stockpiling as if it represents increased consumption, according to Toril Bosoni, head of the IEA’s oil industry and markets division.

Chinese stockpiling peaked at a rate of about 900,000 b/d in the second quarter of this year before slowing in July, according to the IEA. Macquarie estimates China is still stockpiling roughly 500,000 b/d and that it will continue to do so for several months.

While China has not provided any explanation for its purchases, Macquarie’s Dwivedi said Beijing may be building a larger reserve in case more aggressive western sanctions eventually choked the eastward flow of Russian and Iranian oil.

Amrita Sen, founder of consultancy Energy Aspects, said China’s stockpiling was part of its “de-dollarisation” strategy to help counter any potential devaluation of the renminbi if a trade war with the US escalates. She expected the buying to continue in 2026.

Central to the IEA’s analysis is the forecast that global oil consumption will increase by only 700,000 b/d next year to 104.6mn b/d, which would represent the slowest demand growth outside the pandemic since 2009. It expects production to rise by 2.7mn b/d this year and by 2.1mn b/d next year to reach a record 107.9mn b/d.

However, even the IEA does not expect global inventories to increase by 3.3mn b/d next year.

“Something has to give,” Bosoni said. “If there’s no action from suppliers, the balances point to a very oversupplied market, but markets do respond eventually.”

Some analysts, including Sen at Energy Aspects, believe the size of the surplus will ultimately be smaller and the impact on prices less severe. While the consultancy’s figures also imply a glut of 2mn b/d next year, Sen said the firm was likely to pare back its estimate of the surplus once it becomes clear that Opec+ has been unable to increase output by as much as announced.

Opec+ has raised its production quota by 2.5mn b/d since April, but most experts think output will actually increase by less than 1.5mn b/d, given that several members of the cartel have already reached maximum capacity.

“Yes, there will be downward pressure on prices, I just don’t buy into the narrative that we’re going to see $40 oil,” Sen said. “As long as the Chinese bid is there and Opec+ spare capacity is constrained, the downside is going to be protected.”

Macquarie, in contrast, expects a “pretty rapid” collapse in prices.

“If these surpluses are actually as big as advertised . . . at some point, you’re going to have to see storage buildings in the visible part of the world,” Dwivedi said. At that stage, physical traders should start saying there is “too much oil” and the market should “cave in”.

But he added that when too many traders are in agreement about something, it tends not to materialise.

“The problem is, a bear market needs the element of surprise, and this has no surprise in it,” he said.