Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Nepali youth took to the streets this week in protests sparked by a government ban on leading social media platforms, among the biggest targets of their ire were the allegedly wealthy children of the nation’s political elite.

For weeks before the ban, videos were circulating on social media purporting to show the expensive cars, handbags and vacations enjoyed by politicians’ offspring with hashtags such as #NepoKid and #NepoBabies.

The images of apparently extravagant lifestyles among the families of the powerful proved incendiary in a country that ranks 107th out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s annual corruption index and where many say political graft is rife.

After 19 people died in clashes with the police on Monday, demonstrators on Tuesday torched politicians’ homes and government buildings and Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli announced his resignation. On Wednesday evening the health ministry said the total death toll from the turmoil had reached 30 nationwide, with more than 1,000 people injured.

Nirjala Regmi, a 21-year-old student and Gen Z protester in Kathmandu, said suspicions about the lavish lives of political “nepo babies” were the early driver of the demonstrations. “None of us anticipated things to go this far,” she said.

Protests on Monday quickly evolved into a broader uprising that reflected disenchantment with the country’s political class and what many Nepalis see as a broken political system. The government’s move to block access to popular social media platforms, including Facebook and Instagram, that it said had not complied with a mandatory registration process, served as a trigger for young people to vent their anger. One of the placards displayed during protests on Monday read: “We Pay; You Flex”.

Use of the term “Nepo Kids” for the children of the rich, famous or influential first gained traction in Hollywood and later spread to India’s Bollywood film sector and across South Asian political dynasties before becoming established in Nepal.

One widely shared video showed supposed “nepo kids” of Nepali politicians at parties and with fancy cars, interspersed with images of people suffering the mudslides, earthquakes and endemic poverty that blight many lives in the country and of migrants leaving in search of a better future elsewhere.

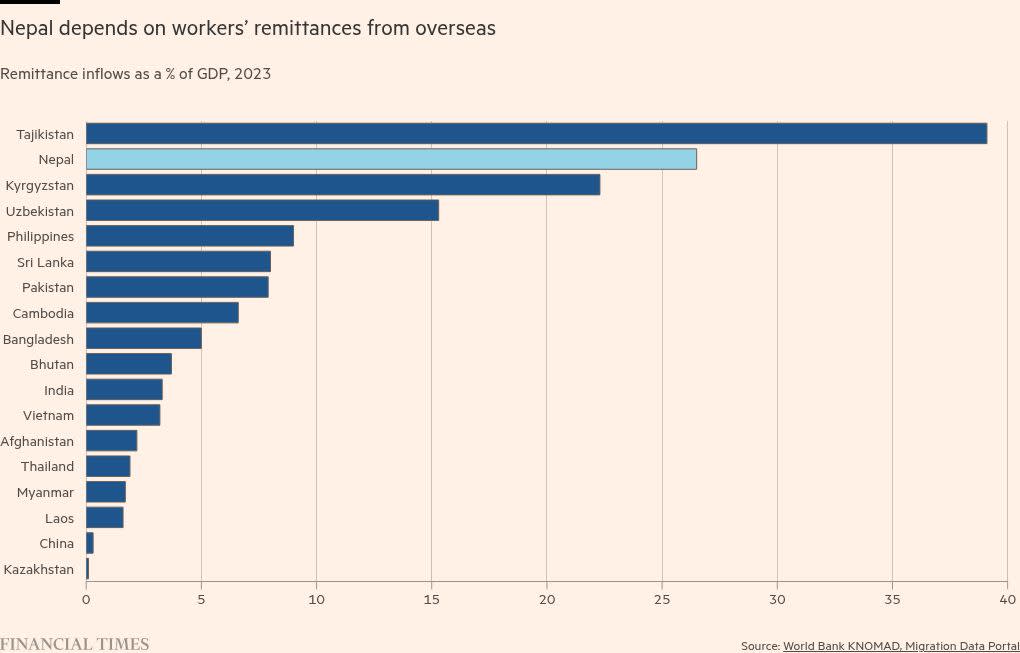

Remittances sent back by migrants working abroad have been “central” to Nepal’s economic growth, according to the World Bank, but have “not translated into quality jobs at home, reinforcing a cycle of lost opportunities and the continued departure of many Nepalis”.

Pranaya Rana, a Kathmandu-based writer, said young people’s anger had been fuelled by seeing the “children of these political leaders, who are their age, on Instagram flaunting their wealth”.

“That was building over social media, and once the social media ban happened, it was like a trigger,” Rana said.

Since Nepal abolished its 239-year-old monarchy in 2008, the country has had more than a dozen governments, a revolving door that protesters complain means politicians from the major parties all benefit, but which delivers little for the wider public.

More than 80 per cent of Nepal’s workforce is in informal employment, according to the World Bank, while the unemployment rate is 21 per cent.

While the end of a 10-year civil war in 2006 brought promises of a new Nepal and a new constitution was enacted a decade ago, many of the main political actors have remained on stage, including Oli, a four-time prime minister.

Some new faces are appearing. Soon after Oli’s resignation on Tuesday, Kathmandu mayor Balendra Shah, a former rapper popularly known as Balen who is not from a mainstream party and is popular among youngsters, called for “Dear Gen Z” demonstrators to “Be restrained now!”.

In a statement issued on Tuesday, a group that described itself as “Generation Z Protesters” said they were “not associated with any individuals or groups involved in vandalism or destruction of public property”.

The army established control of Kathmandu streets on Tuesday night after the parliament, courts and houses of politicians, including Oli’s personal residence, were set ablaze and hundreds of inmates escaped from prisons.

Residents said Kathmandu appeared to be returning to relative normalcy on Wednesday, with President Ramchandra Paudel described as being constitutionally in charge of the government and in contact with the army. UN secretary-general António Guterres called for a “dialogue towards forging a constructive path forward”.

Amid growing political uncertainty, analysts said the president, and possibly the army chief, Ashok Raj Sigdel, would have to sit down for talks with Gen Z representatives to find a way out of the deadlock.

“Beyond the online hashtags criticising ‘Nepo-kids’ . . . the Gen Z protesters coming out on to the streets were determined to have their say on national issues,” said Anurag Acharya, director of Policy Entrepreneurs, a Kathmandu-based think-tank.

“Young people are frustrated that their ambitions, their aspirations for living in a better Nepal are not going to be met in their lifetime,” he said.

Data visualisation by Haohsiang Ko