Hello Swampians, it’s Jonathan Derbyshire here, the FT’s US opinion editor, standing in for Ed, who returns next week after a well-earned vacation (plus an appearance at Saturday’s FT Weekend festival in London; in-person and digital tickets are still available).

One of the books everyone is talking about here in the US at the moment is Dan Wang’s Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future (reviewed recently in the FT by my colleague John Thornhill). Wang’s thesis is simply stated. “China is an engineering state,” he writes, “building big at breakneck speed, in contrast to the United States’ lawyerly society, blocking everything it can, good and bad.” (You may detect a bit of an echo in that characterisation of the US of another of the year’s most discussed books, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance, which trades on the idea that sclerotic regulation and planning blight are stifling America’s growth potential.)

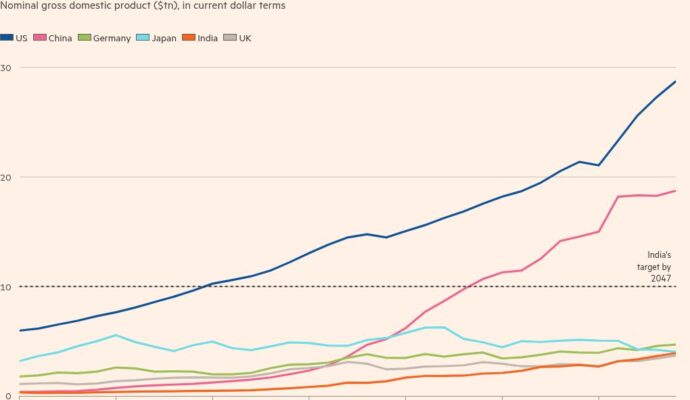

Today, China is a world leader in innovation in a number of fields — electric vehicles, industrial robotics and the solar industry, to name only three. And it’s possible to see this technological pre-eminence, which of course is the cause of much anguish in Washington DC and other western capitals, as the realisation of Made in China 2025, the grand plan to propel China to the frontier of advanced manufacturing announced by President Xi Jinping in 2015.

This has certainly been a “national strategic success for the government”, Wang told Ross Douthat of The New York Times, and a boon for the Chinese consumer. But he thinks it has also “entailed absolutely miserable competition for . . . companies and absolutely miserable returns for their investors”. Pushed to define what Beijing calls “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, Wang said: “The state wins; consumers win. But it is actually pretty rough for . . . companies.” And rough too for free speech and free thinking which Wang says he has come to think aren’t in fact “terribly important” to innovation and commercial dynamism.

Much of the interest in Wang’s book can be explained, I think, by a number of developments which have led some observers to ask if, as a recent article in the Wall Street Journal put it, the US is marching towards “state capitalism with American characteristics”.

In early August, Donald Trump called on the chief executive of Intel, Lip-Bu Tan, to resign, on the grounds that he was “highly CONFLICTED” (capitals the president’s own). At the end of that month, Trump announced a deal in which the government would take a 10 per cent stake in the chipmaker, using previously agreed federal grants to fund an $8.9bn equity investment. One disillusioned Republican said this “opens the door to a sort of state-run capitalism that we conservatives have typically spoken against”.

Also in August, Nvidia and AMD struck a deal with the Trump administration under the terms of which they would hand over to the government 15 per cent of the proceeds of all sales of chips to China.

These deals followed an agreement between the administration and Nippon Steel, which involved Trump withdrawing his opposition to the company’s acquisition of US Steel in return for the government receiving a “golden share” in the resultant merger. My colleagues on the FT’s Lex column said the deal embodied the “golden age of Trump-led meddling” in the US economy.

What’s the rationale for such intervention? Sometimes, as in the case of the Pentagon’s $400mn purchase of a 15 per cent stake in rare earths producer MP Materials, the reason given is national security. As Gillian Tett observed in her column last week, “the White House is deeply worried about national security in general, and rare earth minerals in particular”. Beijing is subsidising its rare earths industry, the argument goes, so the US simply has to do the same.

“A mercantilist, state-run vision of capitalism is now taking hold,” Gillian writes, “particularly (but not exclusively) in the national security realm.” Others aren’t so sure there’s some grand ideological realignment of America’s political economy under way. Michael Strain, also writing in the FT last week, agrees that the Trump administration is abandoning the traditional Republican commitment to free markets and “economic liberty”. But he thinks this is “not so much a strategic embrace of state capitalism as an opportunistic attempt by Trump to ‘get the best deal’ in one-off situations”.

I’m delighted to be able to call on Rana Foroohar to respond this week. Rana, whether one agrees with Gillian’s diagnosis or Michael’s, what is clear is that significant changes in the relationship between government and the private sector are taking place. Where do you position yourself in this debate? And do you think the shifts I’ve been discussing are to some extent continuous with changes that began under the Biden administration, which ran a highly active industrial policy?

Recommended reading

Chloe Cornish’s investigation for the FT Weekend Magazine into “how the Trumps won the Gulf” makes for riveting reading. By the time Donald Trump is scheduled to leave the White House in January 2029 (and we know he likes to tantalise his supporters with the prospect of a third term), he and his family businesses, Chloe writes, will have left “a mark on the Middle East’s petrostates — a Trump tower in almost every major Gulf city, and golf courses shimmering mirage-like in the deserts.”

France seems stuck in a kind of political Groundhog Day, with parliamentary confidence votes and prime ministerial departures having become almost a matter of course. In this excellent column, Simon Kuper suggests that the country’s problems come down, in the final analysis, to profligate fiscal policy. Whether the French classe politique has the will or the wherewithal to fix them is another matter.

Away from the tangled realms of business and politics, I very much enjoyed this review by Jonathan Rée of a new “social history” of analytic philosophy. Rée is particularly good on the often bizarre scenarios or “thought experiments” that are the stock in trade of many academic philosophers, in the English-speaking world at least. “You might almost say,” he writes, “that analytic philosophers can be defined as people who get excited about ‘cases’, however ludicrous or artificial.”

Rana Foroohar responds

Jonathan, great to be back in the saddle. I’ve been on leave for the last month, working on my next book, which is partly about America’s inability to make ships. As I’ve written in the FT many times (see here most recently), America gave up the ability to make its own commercial ships after the government stopped offering subsidies in the 1980s, and the end of the cold war necessitated fewer military vessels. Korea, Japan, and then China took over, making the cheapest and in many cases best ships. But unfortunately, the US is now in a pinch given that it has less than 200 ocean going commercial vessels (which not only get what American needs to port, but service military vessels in times of war) while China has 5,500. If Beijing wanted to put the logistical squeeze on to the US, it would be able to quite easily and effectively.

America simply can’t build ships on its own anymore, because unlike China (or to a lesser extent other Asian and even European countries like Germany or Italy) it didn’t prioritise manufacturing and industrial strategy from the 1980s until Biden came to office. The Biden administration not only put into place a new shipbuilding friendshoring effort with Finland and Canada (which Trump is also pushing), it most importantly brought back chip-building in 18 months at scale. That was a huge success that many economists thought could never happen, but it was a tough job, done by former commerce secretary Gina Raimondo, who is an organisational powerhouse who did a tremendous job uncovering risk in crucial US supply chains.

The Trump administration taking a stake in Intel isn’t about industrial policy — it’s about power and ego. Who will train the engineers and labourers still needed to fuel the industry? Joe Biden had a plan, but Trump wants to get rid of the Department of Education. Who will fix the grids needed to fuel the business? I could go on. Smart industrial policy is tricky even when you have an adept White House. The Trump White House is not that. Just consider what they are doing on ships. At the same time that Trump is using shipbuilding as a chit in Korea/Japan trade negotiations, he’s actually got rid of the White House shipbuilding office, moving its small staff to the Office of Management and Budget, which means there’s no co-ordination hub domestically for efforts anymore. Nobody I talk to in the industry knows what’s going on. The bottom line: rumours of both socialism and industrial policy in Trump’s White House have been greatly overblown. China, on the other hand, has plenty of both.

Your feedback

We’d love to hear from you. You can email the team on swampnotes@ft.com, contact Jonathan on jonathan,derbyshire@ft.com and Rana on rana.foroohar@ft.com, and follow them on X at @RanaForoohar and @jderbyshire. We may feature an excerpt of your response in the next newsletter