Father of the nation Mahatma Gandhi called the cow India’s “giver of plenty”. For nearly 80 years Amul, the country’s biggest dairy farm collective, has linked Hindu beliefs that cows are sacred with Gandhian ideals of social and economic co-operation.

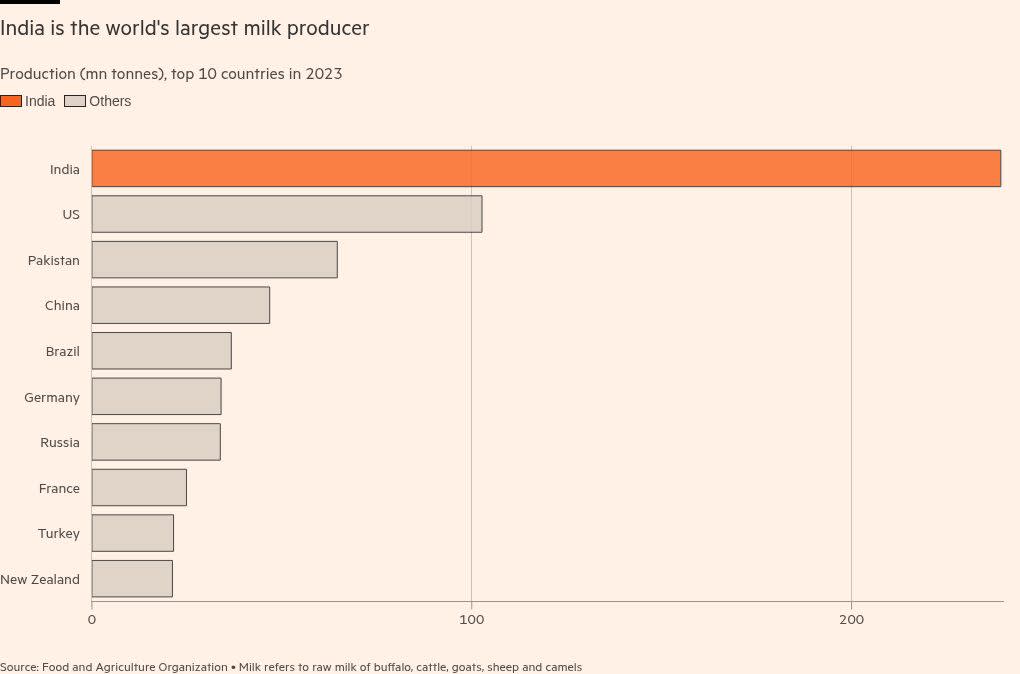

The co-operative model has propelled it to a 75 per cent market share of the country’s milk market and helped India become the world’s largest milk producer — contributing 25 per cent of global production. The industry also benefits from unusually high levels of protection from external competition, a factor that has contributed to stalling a trade deal with the US.

“India is a country with a population of approximately 1.5bn and hence, has an insatiable demand for milk and milk products,” said Vipulbhai Patel, Amul’s chair. In the 2023-24 financial year, Amul’s turnover topped $7.3bn, an 8 per cent increase on the previous year.

Amit Vyas, Amul’s managing director, said the business model, which involves more than 18,000 village co-operative societies, over 3.6mn farmers and a network of more than 1mn retailers, works because “the production, processing and marketing is all owned by the farmers”.

Another factor in Amul’s success, according to Vyas, is its procurement system, which secures 35mn litres of milk a day from cows, buffaloes and even camels. Since it was set up in 1946, Amul has bought everything each of its members produces “every day of the year, rain or shine”, he said.

“Be it one litre or 500, we’ll buy it and pay it on the day,” he explained, adding that privately owned competitors may pay a bit more than the average of Rs39 ($0.45) Amul pays per litre depending on the amount of fat, “but they won’t buy every day; their demands are based on the market”. Amul also provides subsidised cattle feed and veterinary services.

Mittalben Patel, a 43-year-old farmer from the outskirts of Anand in Gujarat, where Amul is based, said that because she was part of the co-operative, she had been able to build a herd of 200 cows from just one, two decades ago. “Amul takes all the milk I produce. The assurance that the product will be taken up . . . is crucial. Private buyers cannot compete with that. There is no better option for me,” she said.

Amul, which makes 4 per cent of its sales from exports to 50 countries, is also looking to expand overseas. Last year, it partnered with the Michigan Milk Producers Association to open a fresh milk plant in the US and it recently opened one in Spain in partnership with the Cooperativa Ganadera del Valle de los Pedroches.

At the same time, it and the rest of India’s dairy ecosystem are helped by high barriers to foreign competition. The country imposes duties of 30 to 60 per cent on dairy products according to Rupinder Singh Sodhi, president of the Indian Dairy Association and a former managing director of the Gujarat Co-Operative Milk Marketing Federation, the top division of Amul. “India does not need dairy from outside,” he added.

Since independence in 1947, India has created tariff walls around agriculture, which employs nearly half the workforce of the world’s most populous country. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has exhorted dairy farmers in his home state of Gujarat to make Amul “the world’s largest dairy brand”.

The sector is shielded from foreign competition in trade deals agreed with the UK this year and Australia in 2022 and in trade talks with the EU. India’s insistence on protecting dairy has been a major sticking point in negotiations with the US, even jeopardising a bilateral agreement with India’s top trading partner, according to people briefed on the talks.

After Trump slapped 50 per cent tariffs on India this month, Modi said he would stand “like a wall” against any policy that threatens the interests of Indian farmers, including dairy.

An EU trade negotiator described Amul as an “Indian state in itself”, representing a group of farmers larger than the total population of Uruguay. The government wants to keep them on its side, so “dairy is completely off trade talks; Amul is a huge constituency”, the negotiator said.

Ashok Gulati, an agricultural economist at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, said the dairy sector in general and Amul producers in particular are “the biggest lobby against any dairy imports” because they “feel they are a sacred cow” that is “not to be touched”.

But Vyas highlights the challenge of convincing younger generations to stick to dairy farming. “We have to protect our farmers. At the end of the day, it’s not about money, not about blocking anyone. It’s about farmers not to be distressed and move away from their livelihoods . . . Everyone has to understand we are talking about people, not just a business.”

Amul was founded in 1946 as the Kaira District Co-Operative Milk Producers’ Union. At that time, farmers were seeking to escape exploitation by intermediaries working for the Polson Dairy monopoly amid Britain’s colonial dominance. They sought help from Sardar Patel, one of India’s independence leaders and Gandhi’s earliest political lieutenants.

He outlined the model of professional management of a union of local village co-operatives, through which farmers would control procurement, production and marketing.

The Amul brand, short for Anand Milk Union Ltd was established in 1957 by Verghese Kurien, an engineer from a Syrian Christian family, who in 1970 launched the “White Revolution” that transformed India from milk deficient to top producer.

Over subsequent decades, the model was exported to other states, creating a network of co-operatives that continues to underpin the dairy industry. Today, the industry provides a livelihood to more than 80mn households and in 2023-24 it generated output of 239mn tonnes.

“Amul’s success is based on taking care of all the stakeholders in the supply chain,” said Sodhi.

Although India opened up its dairy sector to foreign competition two decades ago, the co-op model is one reason it is hard for international food groups to gain much of a foothold. “There is still a bias in the system towards co-operatives, Amul being the most powerful,” said Gulati. In India, as well as its 75 per cent market share in milk, Amul has an 85 per cent share of butter and 45 per cent in ice cream.

Its vast network of milk procurement centres — many farmers cannot afford to travel far to sell their produce — also gives it a significant advantage. It also has one of the longest-running and best-known advertising campaigns in India, courtesy of a hand-drawn cartoon of a little girl in a polka dot dress that first appeared in 1967.

“Danone tried. Nestlé tried. Lactalis tried. Ultimately, they could not surpass the efficient system that we have in our supply chain,” said Vyas.