One of the best things about being filthy rich is the massive passive income it affords you. Ask Singapore. We don’t know exactly how rich they are — that’s a state secret. But we do know how large their passive income is. Can we work out how rich they might be just by looking at this income? We can try.

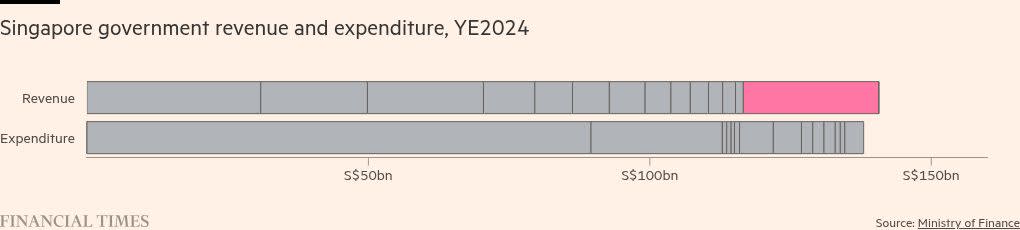

Around a fifth of government revenues come from the NIRC, or “Net Investment Returns Contribution”. This is the dividend that Singapore’s massive sovereign wealth funds pay into central coffers each year — more than income tax or VAT.

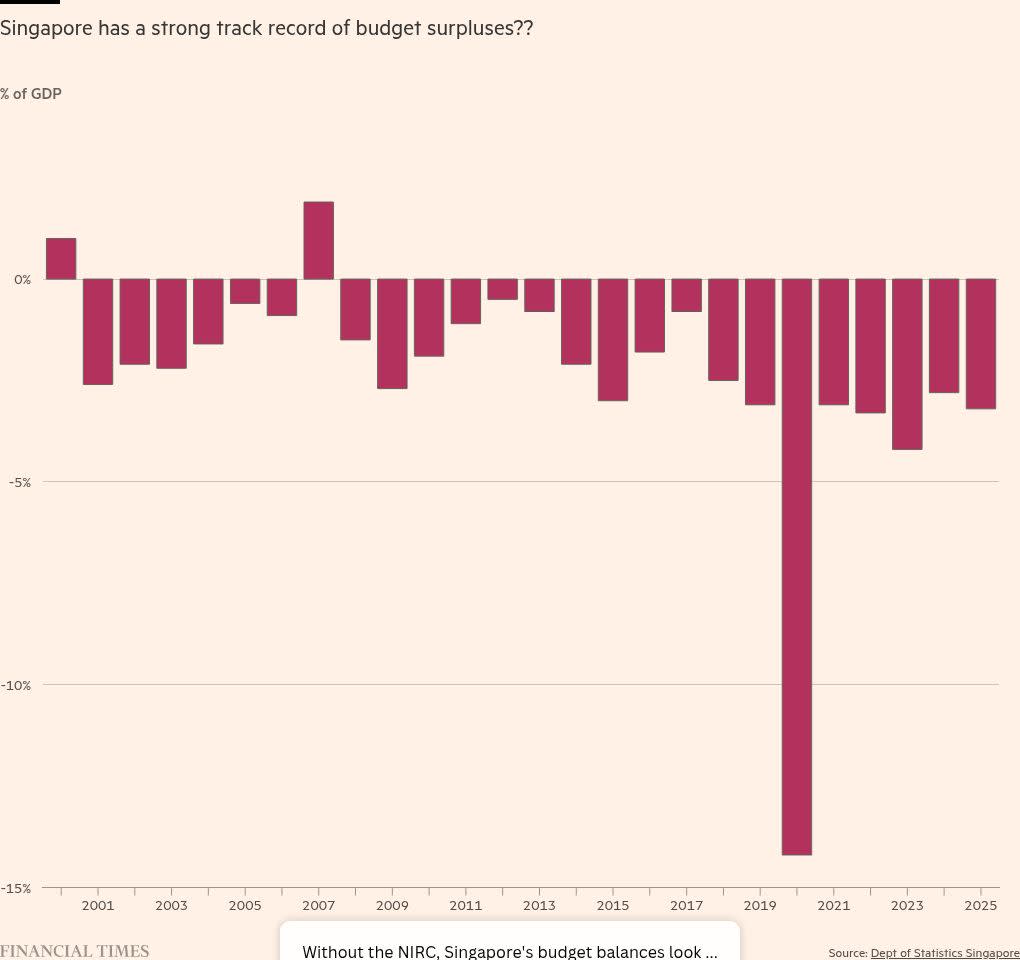

And, as we explored earlier in summer, Singapore appears to have built itself substantial reserves through some combo of budgetary conservatism and successful balance sheet YOLOing. (We omitted the state’s close control of land sales and leases, and multiple readers pointed to this as the third leg of their stool.)

Since 2000, sovereign wealth dividends have meant the difference, on average, between running an annual budget deficit of 2.4 per cent of GDP (before NIRC) and running a surplus.

The formula to arrive at the NIRC is enshrined in Singapore’s constitution. You can read the actual legalese here. And translating into human seems pretty straightforward:

Okay, there’s also a couple of wrinkles around also adding on up to half the net investment income derived from past reserves from remaining assets. We think means other so-called “Fifth Schedule” entities like Jurong Town Corporation, the Housing & Development Board and the Central Provident Fund. Analysts we’ve been in touch with think these are relatively minor.

But going back to our equation, what do these words actually mean?

So what are the ‘relevant assets’?

They include the net assets of Temasek (S$434bn), the Monetary Authority of Singapore (S$58bn), government deposits at the MAS (S$93bn) and of course GIC — the government’s massive asset management arm.

Taking just the nominal sum of these asset pools would lead to a huge number, and incentivise even more central government debt issuance to pump up the numbers. So the constitution says you need to subtract government liabilities, which we understand total S$1,286bn.

But hold on, what are net assets of GIC again? Time to roll out our favourite quote from any Ministry of Finance:

Just as our defence forces do not reveal the full extent of our weaponry and military capabilities, it would be unwise to reveal the full and exact resources at our disposal.

The number seems important. It defines the equation that is used to make Singapore’s fiscal maths add up.

So we got in touch with Rain Yin, lead Singapore sovereign analyst at S&P Global Ratings. She told us that S&P doesn’t actually model GIC assets at all, assuming instead that they will be “at least equivalent to the government’s gross debt stock, as most of the government’s debt is issued to meet the investment needs of CPF monies”.

We can see that in a world where governments can get a AAA rating with sizeable net debt, fussing over the quantum of Singapore’s net assets is probably immaterial to their rating, so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

In contrast, GlobalSWF makes a stab at estimating GIC’s net assets, and come to a figure of $936bn, or just a smidgen over S$1.2tn. Diego Lopez, the company’s founder and managing director, says he models it by tracking inflows from the government, outflows through the NIRC, and triangulating the annual performance through longer-term return disclosures published over the past 25 years. It sounds like a pretty sensible framework, though we can’t be sure how close it will ever be to reality.

And so our running total for ‘relevant assets’ look like an unknown number minus S$700bn. Hmm.

ELTRROR?

Is there more clarity over the “expected long-term real rate of return” that we set at X in our formula? Nope.

Apparently there is a “rigorous process in place for determining the ELTRROR of the investment entities”, starting with recommendations from the boards of GIC, MAS and Temasek, then flowing through the Singapore MOF, before hitting the president’s desk. S/he consults a Council of Presidential Advisers, and either agrees or disagrees. If s/he agrees, yay! If s/he disagrees, the whole thing defaults to a 20-year historical average real rate of return.

We’ve seen worse frameworks. And the current president — Tharman Shanmugaratnam — is well-placed to navigate this, having previously served as minster of finance, chairman of the MAS, and deputy chairman of GIC.

Can we see the workings? No. How about whether Singapore has defaulted to historical average rates of return? No. But can we at least see the current expected return? Not a chance.

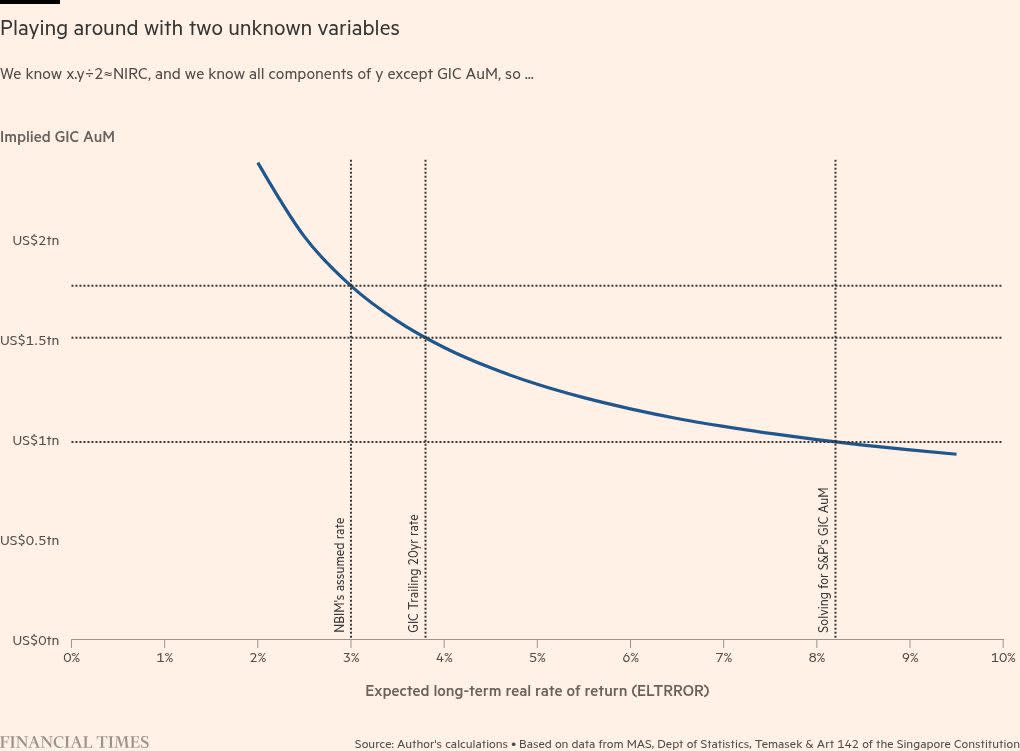

Can we back-out an estimated size for GIC?

Lian Chuan Yeoh, a partner at law firm Withers KhattarWong, got in touch with us to point out that we could try estimating GIC’s size by backing it out of the NIRC equation — even if both variables are unknown.

Because, given that NIRC = (relevant assets X ELTRROR) ÷ 2, and given that we know that NIRC was S$24bn in 2024, and given that the big unknown quantity in relevant assets is GIC assets (again, leaving aside other Fifth Schedule entities) we can have a look at what mix of GIC assets and ELTRROR values gets us to S$24bn.

We appreciate that the chart looks intimidatingly like the sort of thing you left behind in high school maths. But it’s interesting. It seems to imply that GIC is radically larger than every other estimate we’ve seen.

GIC report its 20 year historic real return as 3.8 per cent per annum. If the ELTRROR was 3.8 per cent GIC assets would need to be around $1.5tn to make the maths work — larger than China’s CIC, and almost as large as China’s SAFE.

If Singapore have been using the long-term real rate of return of around 3 per cent that NBIM — Norway’s massive oil pension fund — thinks reasonable, it would imply that GIC was worth $1.8tn (again, leaving aside income from Fifth Schedule entities).

This year the NIRC is rising to $S27bn, implying either even larger net asset values for GIC (or a higher ELTRROR). And this is in the context of investment returns from Temasek that have reportedly been sufficiently low to prompt an organisational shake-up.

Long term return assumptions that might realistically be being made by the Singaporean president could imply GIC assets that would make it the largest SWF in the world.

It feels like we’re missing something. We wondered whether maybe we’d misread Article 142 of the Constitution, included the wrong set of MAS assets or maybe even included bits of government debt that should be excluded from relevant assets. Maybe the net investment income from remaining assets was bigger than we’d understood? We contacted the Ministry of Finance, shared our workings and asked for help.

Did their response help us unpick the secrets of Singaporean state wealth? Sadly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the answer is no.