Good morning. Many of you have written to us over the past eight months asking for longer interviews with India’s top decision makers. So here we are! Welcome to the inaugural edition of the India Business Briefing Q&A series, where we bring you an in-depth interview with a senior industry leader on the last Friday of every month. We have handpicked guests from various sectors to bring you deep insights about the economy, companies, technology, finance and more.

For today’s edition I sat down with Vivek Pandit, senior partner and co-leader of McKinsey’s private equity and principal investment group, to talk about India’s economic prospects and the country’s attractiveness as an investment destination. Pandit, who is based in Mumbai, has been with McKinsey for 25 years advising the world’s leading investors and shareholders. Let me know what you think!

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Although India’s GDP is growing at a faster rate than the rest of the world, the rate of growth has slowed in the past couple of years. Can you help put this in perspective?

A decade ago, India analysts used to say that over the next 25 years, we’re building three new Indias. That was just a recognition that our GDP was going to increase by that much, but we weren’t quite sure where that was going to come from. In 2008, India was about 2 per cent of global GDP. In 2023, we were at 3.5 per cent. I believe that by 2040 a reasonably ambitious target would be 8 per cent. Our confidence in being able to achieve that is a lot higher today than it was 15 years ago.

What gives us that confidence? Where are the bigger opportunities for India?

We see an additional $1.7tn to $2tn of GDP coming from 18 strategic “arenas” by 2030. They are strategic because they represent a combination of import substitution, export potential and play to India’s advantages. These high value-added areas require R&D, capital investment and patent protection. We see auto components growing from $75bn today to $175bn by 2030, semiconductors from $70bn to $250bn, EVs and batteries from $10bn today to $50bn, medical devices $15bn to $30bn . . . the list goes on.

The biggest opportunities of growth ahead of us rely on a combination of domestic consumption and import substitution. In sectors like medical devices, aerospace and defence equipment, bio pharmaceuticals and renewable energy equipment, we are at an interesting point in time where we have large domestic consumption markets as well as the ability to be globally competitive in exports.

With Indian goods now facing Trump’s 50 per cent tariff, can we still hit the growth target? Is a trade deal with the US important?

Maintaining a 7 per cent growth rate requires export growth. In my view, this discussion about focusing on domestic consumption to replace the loss of not having a deal is misplaced. Without a deal, we are going to see a reduction in GDP growth. FDI, especially from the US, is going to slow down. There will also be an impact on employment. In India the narrative sometimes is that our total exposure to the US is small, but it misses the second order impact on jobs, especially on sectors like textiles.

There’s been some talk about reciprocal tariffs. But I would be very careful about that. The Trump administration has exempted services, pharmaceuticals and other sectors for now, albeit in its own interest. But if it comes to a full-fledged tariff war, these industries could also be affected. It’ll have a very significant impact on India’s ability to continue to export technology services and maintain its position with global capability centres.

To put it simply, if you look at the last 30 to 40 years, there are only 10 to 12 economies in the world which have grown at 7 per cent for 20 to 25 years, and none of them have done it without export markets being a significant part of that growth.

Foreign direct investment flows have slowed for four years consecutively. You meet a lot of global investors. What are their perceptions about investing in India?

What they love about India is its political and economic stability. They believe that India has lower geopolitical risks than some of the other high-growth markets.

But there are six areas where India can make substantial improvements to give investors the confidence to mobilise more capital into opportunities that they currently aren’t so excited about. One is, of course, valuations. They’re not excited about valuations, because India is a highly valued market, so that’s just an entry point question for most investors. The others are ease of doing business, currency risk, tax regime, contract enforceability and ease of access to people and capital.

Why does the ease of doing business continue to be a problem?

I’m hopeful that the deregulation commission (set up by the government to identify and reduce excessive regulation) will start to look at many aspects of this. A basic expectation is that you should be able to enter and leave the country without a lot of friction. Investors want to set up new facilities, expand to new states, get export permissions etc. But the pace at which they can be up and running in India is an investment return killer. Time works against investors and these clearances take too long. Therefore, investors either don’t approve those projects because of the delays, or they underwrite a lower return.

This is where China did so well. You could put up factories rapidly, get clearances and start seeing shipments and revenues very quickly.

Which sectors are these investors most excited about?

On top are pharma and healthcare, technology, and financial services. And then come transportation and logistics, machinery and industrial goods, telecoms, energy utilities. Then you see a big gap in interest and then auto components, engineering and construction come after that. Agriculture, minerals and mining are at the bottom of the list.

This list tells you a couple of things. Number one, the dire need to mobilise private capital into areas that actually do produce jobs but are not considered very attractive by foreign investors. This means that you’re going to have to mobilise domestic capital into some of these manufacturing opportunities, and only once foreign investors start to see local entrepreneurs succeed in navigating this will they bring in their money.

The second is that investors like businesses that are export oriented and tech oriented. This is something India should take advantage of. The country should build capacity in industrial and renewable equipment manufacturing, where there are opportunities in the domestic market as well as for export. The problem is PPE (property, plants and equipment) generally has a slower rate of return in India than it does elsewhere, because of the difficulty in acquiring land and getting import licences.

Moving on to other investments. What does the private equity landscape in India look like now?

The PE business is like that line from the tale of two cities — best of times and worst of times. The good news is that Indian deals are doing better — we are seeing more exits, better returns and more funds being raised. We are also seeing movements into more asset classes; people who were doing private growth are now doing private buyout, people who were doing buyouts are now looking at credit, and so on.

The bad news is that in sectors like pharmaceuticals, technology and financial services, capital is not being used to build new capacity. It is instead being used to buy out existing investors and improve operational efficiency. This is where you get the best returns in India.

Sectors such as infrastructure, climate change and energy transition are interesting to investors. Some of the largest investors have produced some of the best returns. We have seen net returns from significant pools of capital in excess of 40 per cent. And when I say net, I want to be clear, net dollar. If you take the average basket, it’s about 14-16 per cent. These are not bad returns, unlike say 15 years ago, where, frankly, there were concerns about whether India was worth the risk. We are now also seeing the rise of domestic private equity.

My biggest mistake

I wouldn’t know where to start (laughs). One, I’d say, is not truly starting the journey of self reflection and working on my inner self earlier. I started only eight years ago and it took external events to trigger it. I’d run a long and successful career operating on adrenaline, and that’s no longer sustainable. The shift to a more fluid, more accepting approach requires significant internal rewiring. I’m happy I started that journey, but I also wish I’d started earlier.

We have had a slew of IPOs this year but very few blockbusters. What’s your view of the primary market?

IPOs are super important because private markets can’t continue to fund these businesses. There is no other exit, outside of a strategic buyout, and at the valuation at which private companies trade, the probability that you’ll find someone willing to buy out companies without making valuations severely diluted is low.

There are three things the market and regulators have to maintain to make sure public markets continue to stay excited about the issues. One, there is a tendency to price everything to perfection. Investors need to see value. The second is that in the past few years, the boom in real estate made capital allocation to IPOs difficult. We are perhaps seeing that cycle come to an end. Third, the unsecured credit that was flooding the markets was not helping. That too has reduced now.

India has constantly been spoken of as being on the verge of greatness for at least the past two decades. When will we arrive?

I think that is the old adage, right? We disappoint both the pessimists and the optimists. India’s politics, and therefore its policies and its economy, has had to tread a very fine line between lifting people out of poverty and diverting capital productively. India’s average consumption basket is still 46 per cent food. And so our ability to navigate, what we call, inclusive growth, moves in fits and starts.

The biggest opportunity right now is trade — imports and exports. India needs to be seen as a place that has frictionless access to export markets around the world. And for that reason we need to get a deal done with the US. There’s no deal that we’re going to do that’s going to change the fate of 200mn people in poverty. But what our policymakers have to believe is that doing a deal with the US and lowering import barriers is not bad for the common man, it’s not bad for job creation. In fact, it is net positive for job creation.

Now, you asked a very pointed question. When will India arrive? At what point can you feel you are successful when you look behind your shoulder and see so many people who have not been lifted by inclusive growth? While it will be a long time before we can declare victory on lifting all boats, I think it’s a short run to 2030, when we will be the third-largest economy in the world and a significant trading partner.

After hours

I read a combination of books and research papers on the psychology of leaders, of groups, of organisations; how they adapt, why they don’t adapt, things like that. A quote that stayed with me from these readings comes from Navy Seal trainers: people don’t rise to the occasion, they fall to their level of training.

I love sports. I used to play tennis, squash and football. Now, let’s just say my mental faculties are far ahead of my muscles, so I want to make sure I don’t come off the field in a stretcher. I have recently started playing padel, and I quite enjoy it.

As a family, we also travel quite a bit. My wife is a teacher of history, and two of my children play music, and one is a dancer. So we pick places that appeal to all our interests. This year we spent time in San Francisco and Marrakech, while last year we travelled to the coast of Turkey and Greece.

Recommended stories

China gains from Trump’s alienation of India.

In tech news, Nvidia’s growth outlook has been hit by China uncertainty, and we have a read on Xiaomi, the country’s gadget maker taking on Tesla and Apple.

Inside India’s endless trials.

How to dodge the tourist traps.

Should you be taking creatine?

Luxe boxers, anyone? The traditional underpants are more popular — and expensive — than ever.

Read, hear, watch

I managed to lay my hands on Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me the day it hit the shelves (my kind of first day first show). I had spent the last few weeks in envy, as my more influential bookish friends flaunted their advance copies. The reviews are great. I’ll speed read it tomorrow and then submit myself to a more languorous second read next week.

I have also been uncharacteristically organised these last few days and booked tickets for The Roses, a black comedy about ambition in an unhappy marriage starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Olivia Colman. The clips I have seen on social media are fantastic. This is the best weekend in a long time for my specific kind of nerdery. *Rubs hands in glee*.

Buzzer round

If you spot Saint Peter’s Dome or the Palace of Justice, and pass under the Sant’Angelo bridge, which river are you floating on?

Send your answer to indiabrief@ft.com and check Tuesday’s newsletter to see if you were the first one to get it right.

Quick answer

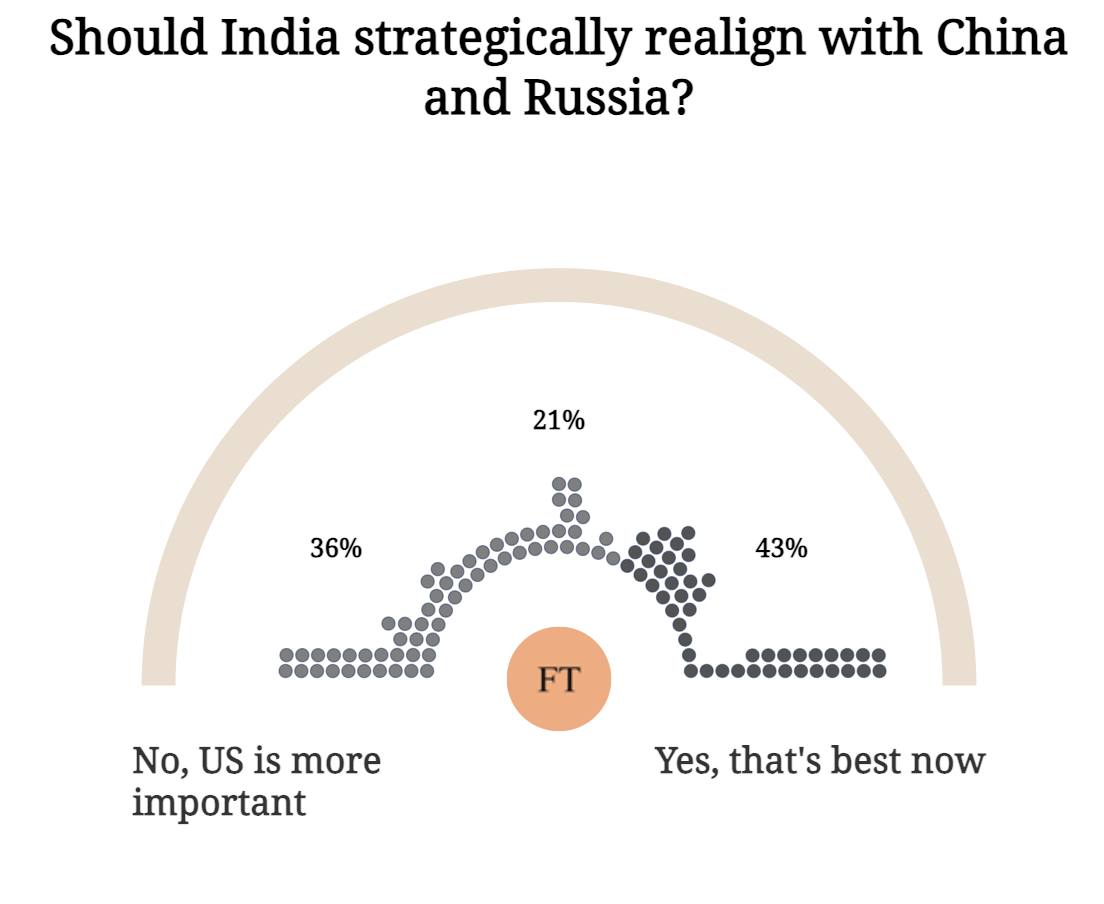

On Tuesday, we asked if India should strategically realign with China and Russia? Here are the results. It’s a bit all over the place, but more people seem to think that is the best option for now.

Thank you for reading. India Business Briefing is edited by Tee Zhuo. Please send feedback, suggestions (and gossip) to indiabrief@ft.com.