Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Japan believes that it can help African governments reduce high cost debt repayments built up in the last decade when China increased its lending to the continent.

Tokyo is strapped by the same fiscal pressures and rising right-wing populism being felt across the west making support for any large increase in aid spending hard to find. At the same time, its companies remain highly cautious about investing in Africa.

Despite those challenges, Japan sees potential in redirecting international debt financing to African governments, as south-east Asian countries — the heartland of Japan’s development efforts for decades — become self-standing economies.

Naoki Ando, senior vice-president of Japan International Cooperation Agency, the implementing agency of Japan’s aid policy, says that the country will stick by its model of development assistance over aid. Pressures at home would make it hard to directly plug the gaps left by the US and Europe in healthcare and agriculture, he says.

“There’s a lot of strong headwinds against JICA’s activities on the African continent and official development aid overall . . . even in Japan, our ‘country first’ is spreading,” he says, referring to the rise of Sanseito, a far-right populist party that secured 14 seats in last month’s upper house election with its “Japanese first” slogan.

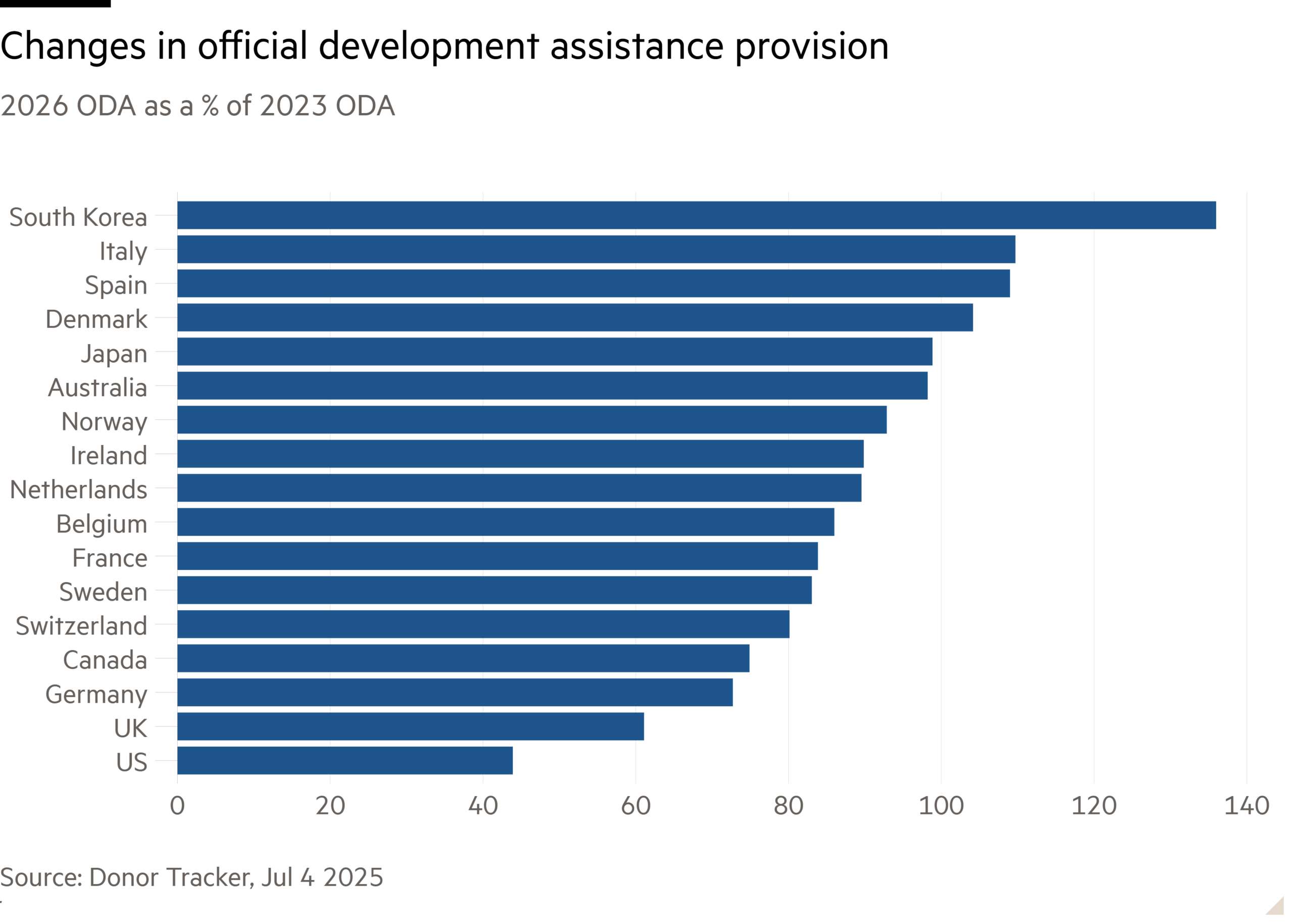

But he adds that Japan remained committed to African development, citing figures from Donor Tracker that showed Japan had not suffered the same collapse in aid budgets as the US, Germany, France and the UK had.

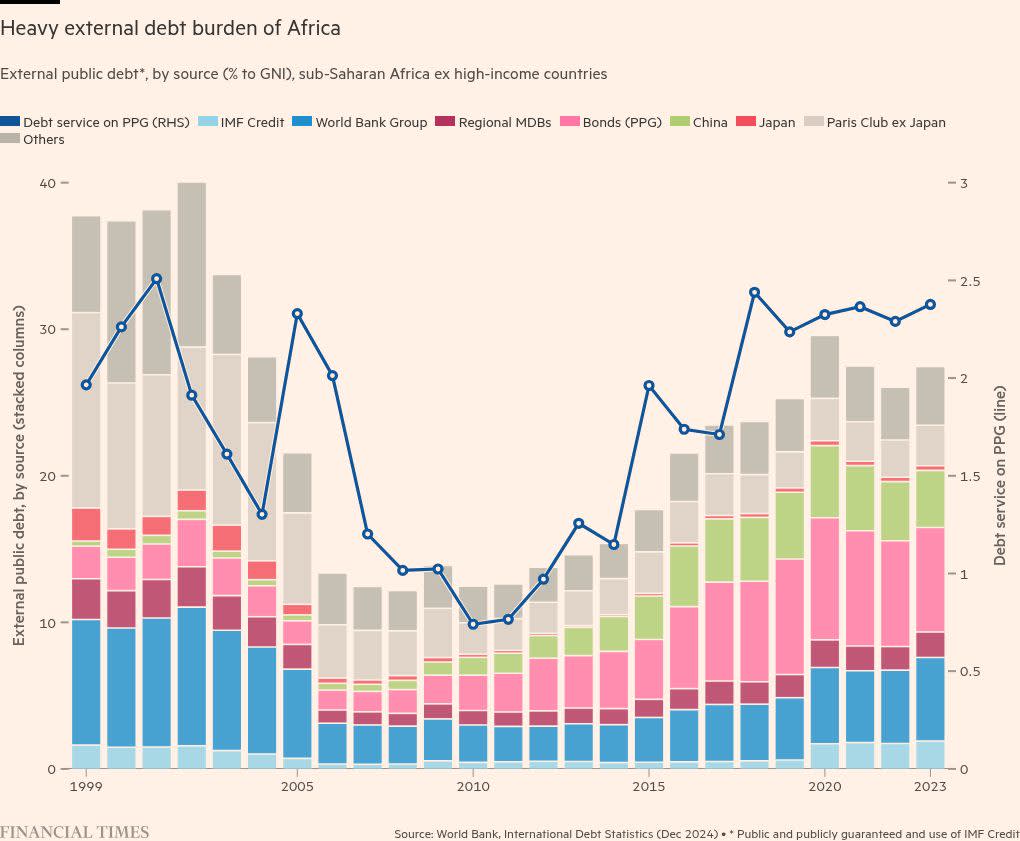

There is even scope for Japan to do more without increasing spending, he says. As public loans extended to countries in south-east Asia get repaid, new loans can be dispensed to African countries that help to reduce their debt servicing costs that have risen to the highest level in more than two decades and are about 2.4 per cent of gross national income.

“Converting high cost debt into concessional debt [low interest debt] is really important to stabilise the African continent,” he says.

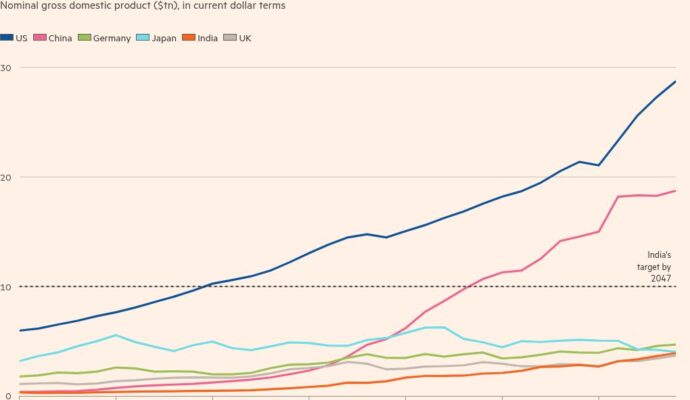

The move would help to create an alternative to the high-cost lending by China to African countries, since it launched its Belt and Road Infrastructure programme in 2013, that has been a partial cause for African debt servicing costs to balloon. Japan’s foreign ministry said that “if current major ODA loan recipients such as ASEAN countries and India graduate from ODA, it would be possible that Africa become the next major recipient of ODA loans”.

More from this report

The rising amount of Eurobonds issued by African governments have been another reason behind the surge in debt servicing costs, as well as the 2015-16 slump in commodity prices that hit many resource-exporting nations’ economies.

The move would also amount to Japan offering African leaders a way to ease the toll of the impact from US President Donald Trump’s cuts to USAID and the pullback in UK and European aid spending.

The new leg in Japan’s Africa strategy comes ahead of the ninth Tokyo International Conference on African Development this month. Ticad, which was first held in 1993, was initially aimed at currying favour among African leaders to get Japan a seat on the UN security council, political scientists have argued.

The conference was reshaped under late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe from a focus on development to promoting investment by Japanese companies seeking to tap into Africa’s rapidly growing population.

But the slow pace of Japanese investment into the continent will be an inescapable truth facing African leaders travelling to Japan. Japan’s foreign direct investment stock has increased 18 per cent since 2014 to Y1.42tn ($9.6bn), a fraction of the near-trebling worldwide.

Keiichi Shirato, director of international relations at Ritsumeikan University, says that momentum behind Ticad peaked about a decade ago when Japan pledged a pivot towards investment but “it totally failed” as a groundswell of investment did not materialise.

“The government of Japan did everything they could do for the private sector but unfortunately the total amount has not increased [much],” he says.

Ando at JICA put the private sector’s cautiousness down to its philosophy of “development first and then business is coming later” and said the hope is to replicate in Africa the successes of that model in south-east Asia.

But more fundamentally, African leaders want a viable alternative for inbound investment into their economies to hedge against China and may be unable to wait for Japan Inc to take the risk.

Japan has given Y1.2tn ($8.5bn) for 80 infrastructure projects across Africa since 1993 but that figure pales in comparison with $182bn of loans that Chinese lenders have committed to Africa since 2000, according to a Boston University database.

While Japan will struggle to fill the gaps left by traditional aid donors and to challenge China directly on huge infrastructure projects, the country will still try to forge its own path to create alternatives for Africa.

“Japan cannot confront China across the board in Africa,” says Howard Lehman, a University of Utah professor and editor of Japan and Africa: Globalisation and Foreign Aid in the 21st Century.

“What it will seek to do as a middle power in Africa is focusing on areas they can do better than China,” he adds, suggesting small-scale infrastructure and capacity building.