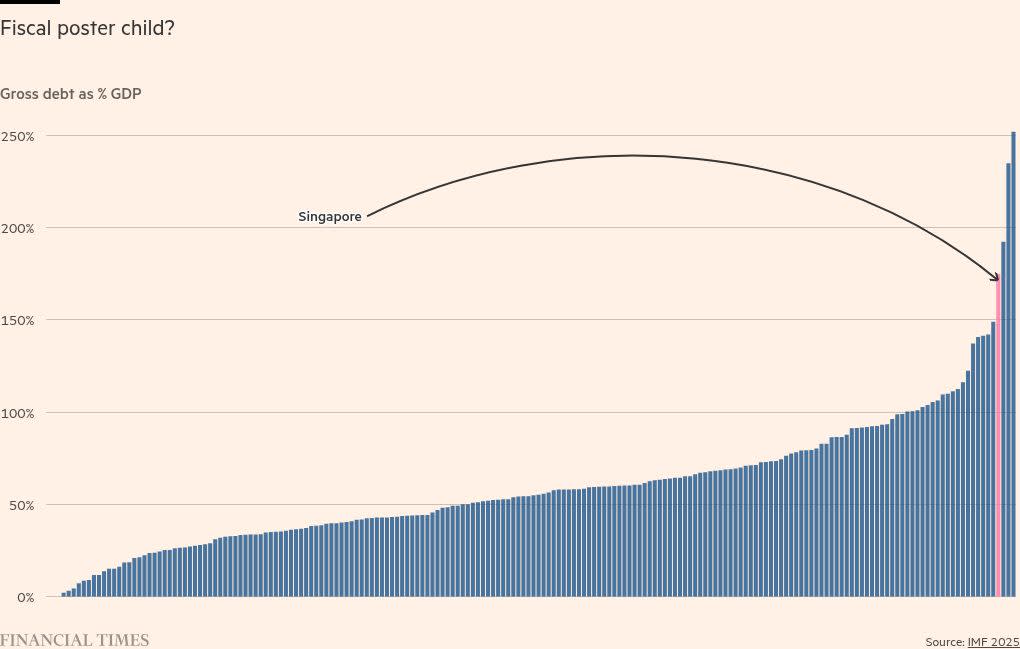

Debt levels are high for developed market governments the world over — even Singapore. In fact, when it comes to gross government debt, Singaporean numbers put not only Italy and the US to shame, but also Lebanon and Greece.

One reason Singapore escapes being lumped into the column headed ‘fiscal basket case’ is its ownership of massive sovereign wealth. While Singaporean has one of the highest gross government debt loads in the world, its net debt is allegedly negative.

We say allegedly, because while a gross figure can be counted, the precise numbers going into net debt calculation are a state secret. Or as the Ministry of Finance puts it:

Just as our defence forces do not reveal the full extent of our weaponry and military capabilities, it would be unwise to reveal the full and exact resources at our disposal.

But given that the Singaporean constitution forbids the government from borrowing for current spending over its term and their history of budget surpluses, we should probably take their word for it.

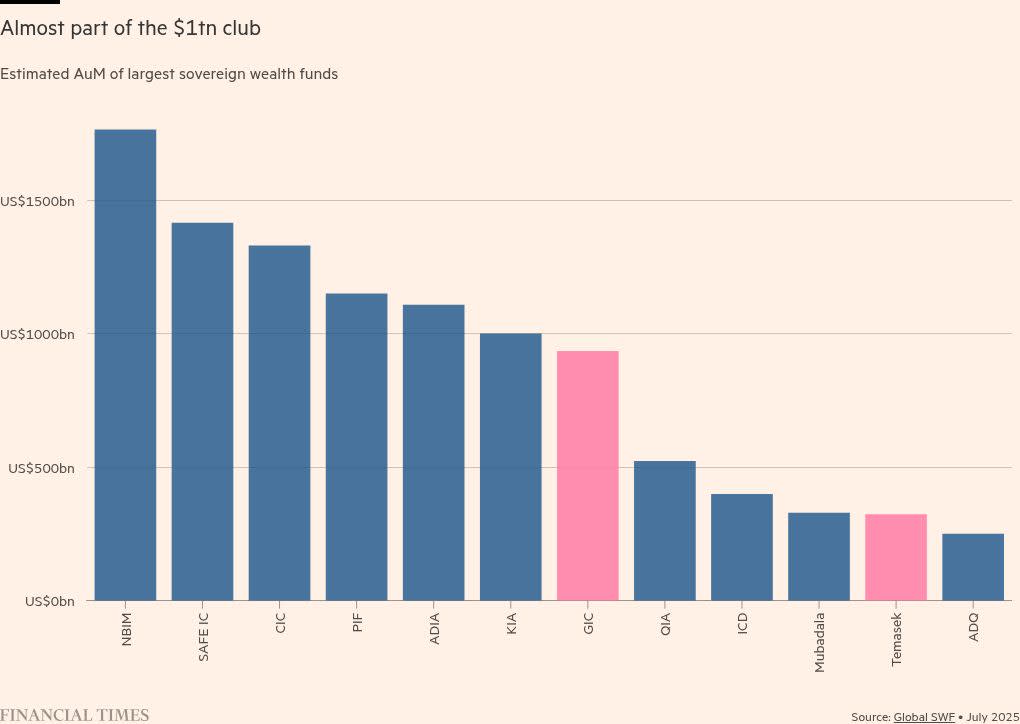

The tiny island city state has two vast sovereign wealth funds — Temasek and GIC — on top of FX reserves held at the central bank. And this got us wondering: where did all this money actually come from? And how good have returns been?

Temasek is straightforward. The country’s original SWF had bestowed on them a bunch of state-owned companies in 1974 valued at S$354mn. Fast forward to 2025, they still own ten of the initial firms, but look to have divested and traded their way to a portfolio they say is worth S$434bn (US$324bn). So even if performance has been a little pedestrian in recent years, it looks like they’ve achieved spectacularly good returns over the long run.

Yay active management! 🥳

But GIC? While its assets under management are not publicly disclosed, GlobalSWF reckon that they are close to three times Temasek’s, and banging on the door of the trillion dollar club, at US$936bn. This would make it the seventh largest SWF in the world. And it’s an odd fish.

Despite publishing a glossy annual report each year that stretches close to 100 pages, we know very little about GIC’s asset allocation beyond it being around half invested in equities, a quarter in fixed income and a quarter in real assets.

And we are told that GIC funds come from the Singaporean government. Specifically, they are attached to the machinations of two different parts of the state — the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the Central Provident Fund. And with these funds come certain liabilities.

MAS excess reserves

Founded in 1981 to manage a chunk of MAS’s FX reserves, GIC was originally conceived of as a way to boost returns on central bank official reserve assets. Since then, further slugs have been periodically transferred whenever the MAS’s interventions to prevent appreciation of the Singaporean dollar left it looking too flush.

But FX reserves are not costless — they have Singaporean dollar counterpart liabilities. Given the managed currency peg, when foreigners make money betting on a strengthening Singaporean dollar, it’s the central bank that has sat on the other side of this trade. And the Sing dollar has been on a tear over the last four decades. Put another way, the asset (foreign currency for which MAS traded Singaporean dollars) has devalued against the liability. So GIC will have needed to have produced decent investment performance on its foreign currency assets to break-even.

Moreover, while there’s no immediate reason why foreigners might want to dump their Singaporean dollar holdings, the possibility that they might appears to underpin the structure of the MAS’s financial relationship with GIC.

Since 2022, the government has issued just over 36 per cent of GDP’s worth of special non-tradeable RMGS bonds to MAS in lieu of fresh chunks of FX reserves that they’ve handed over — which the government then passes to GIC for management. And these bonds are perpetually putable at par — a novel feature we’ve never seen before. We can only guess that this is to allow for swift withdrawals in the event of a run on the currency. We don’t immediately know the quantum of reserves handed over before this date.

To understand the other major source of GIC funds we need to dip into the world of Singaporean pensions.

Singaporean pensions? Do we have to?

Yes. The Central Provident Fund is what pension wonks would call the nation’s mandatory notional defined contribution scheme. This is a boring but (somewhat) concise way of saying that Singaporean residents are obliged to save money into special segregated accounts that show account balances, but are devoid of any actual assets.

OK, that’s not strictly true — the CPF is backed by Special Singapore Government Securities, which are non-tradeable interest-bearing bonds issued by the state to the CPF. But other countries running pension funds backed only by government IOUs are called unfunded so it feels wrong to make an exception in Singapore’s case.

The state doesn’t splurge the proceeds of this bond issuance on current spending. It passes it to GIC to be invested. But the state retains all the upside (and all the downside). And so it’s massively leveraged to GIC investment performance versus CPF funding costs.

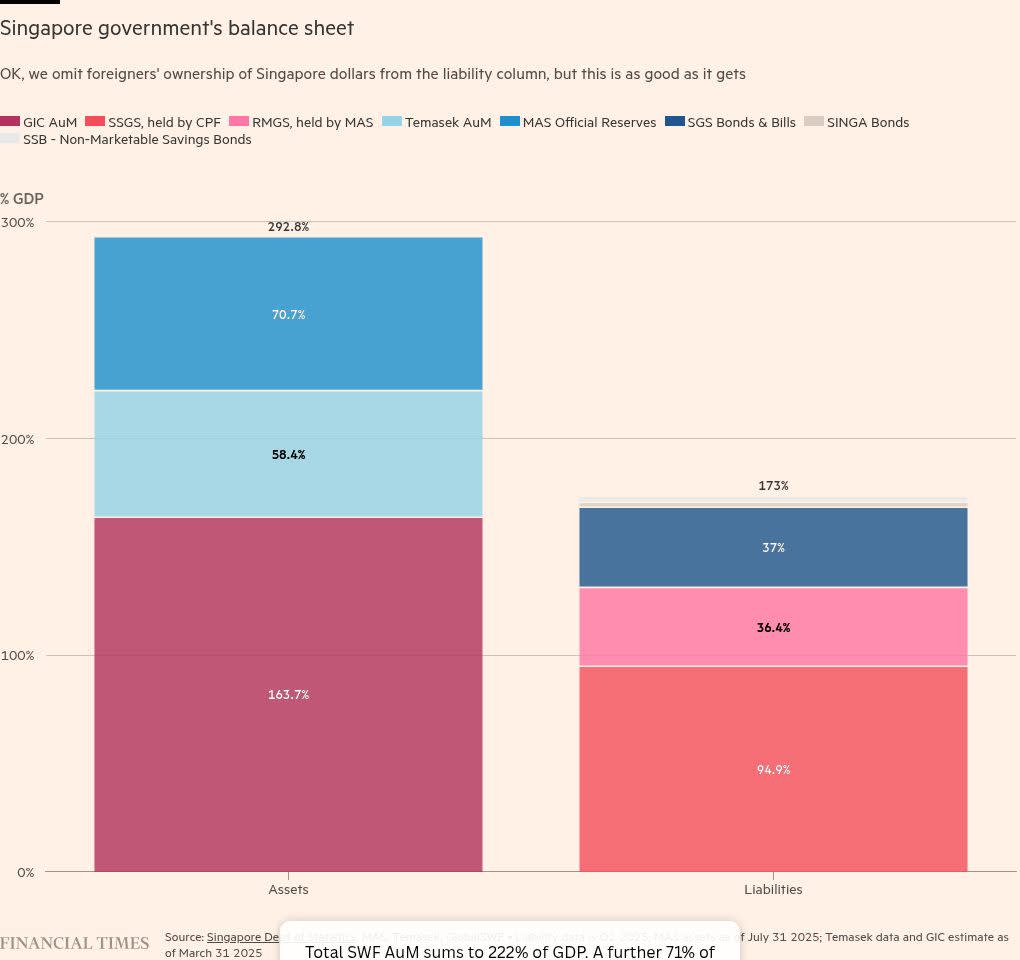

Putting this all together, we made this nice chart showing our guesstimate for Singapore’s sovereign balance sheet:

Monetary pedants might observe that the size of FX reserves is really a function of foreigners’ appetite for the Singaporean dollar, which could turn on a dime. And if they were really pernickety they’d go on to point out that the liability column — aside from the RMGS line which counts excess reserves passed over by MAS to GIC since 2022 — omits that portion of the Singaporean dollar monetary base sold to foreigners and against which the MAS would need to liquidate GIC holdings to defend their managed crawling peg currency regime.

But putting aside these trifles, the chart shows a substantial net asset position — consistent with the country’s allegedly negative net debt.

What about GIC investment performance?

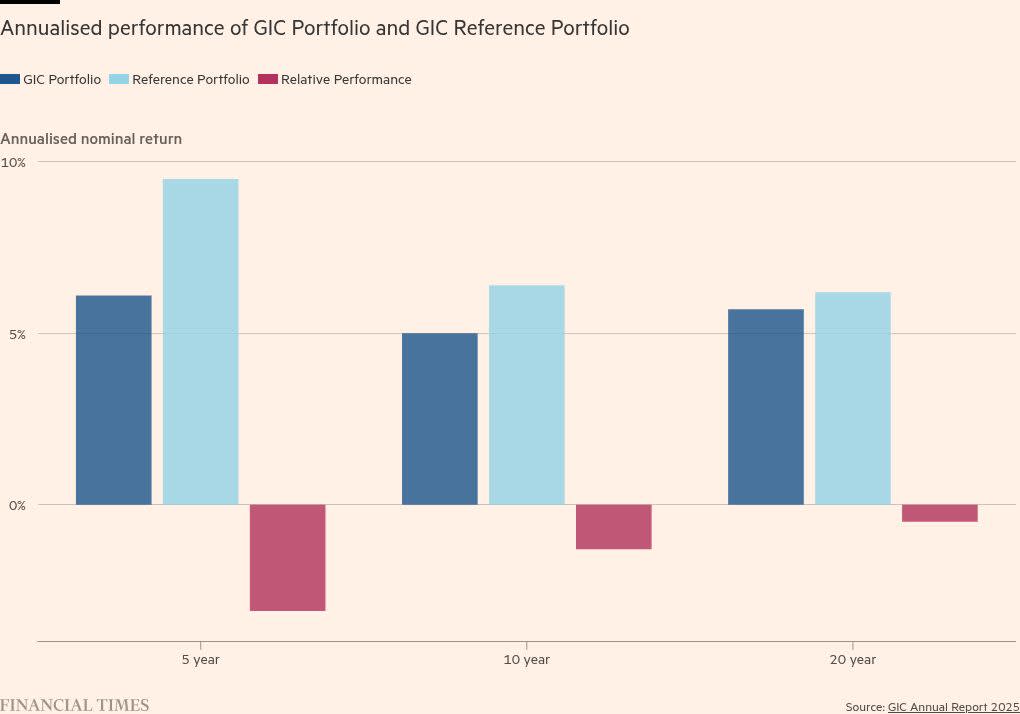

Given how the MoF goes all secret squirrel on GIC deets you’ll not be surprised to learn that they don’t publish annual performance numbers. But they do release longer-term figures. And over the last twenty years they delivered an annualised return in US dollars of 5.7 per cent.

Is 5.7 per cent per annum good? It depends.

Compared to the fund’s benchmark Reference Portfolio — consisting of 65 per cent global equities and 35 per cent global bonds — it’s not great.

Over the last five year they’ve compounded a performance that has lagged their Reference Portfolio by 3.1 per cent per annum. These sort of numbers would make even a US mutual fund manager blush.

Still, compounding 5.7 per cent per annum over twenty years more than triples your money. And when your money is a sovereign wealth fund worth a large chunk of GDP, this sounds far from awful.

But remember, the counterpart to GIC’s assets are debts owed to Singaporean CPF account holders and the MAS. If assets grew at a 5.7 per cent annualised pace, then how about these liabilities?

The first form of liabilities are to the MAS — in case they need FX reserves back to defend the currency peg. As we’ve outlined above, we’re not quite sure how big a number to put on FX reserve liabilities. But it looks safe to say that GIC will have handily outperformed overnight Singapore dollar deposit liabilities.

The second form are to the Central Provident Fund. CPF account holders get promised all sorts of different interest rates on their Singaporean dollars depending on all sorts of things like saver’s age, purpose of savings etc. Rather than piece together years of rates and balances we dived into the accounts and took the money-weighted average rate paid out. And owing to various rate floors, it is persistently higher than the market cost of borrowing:

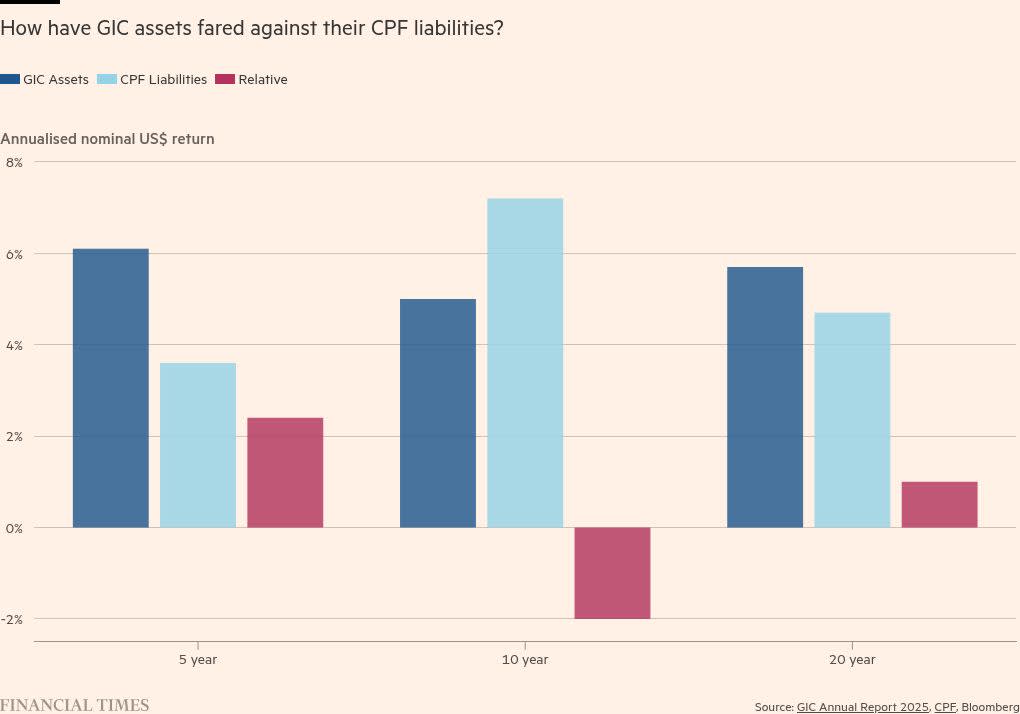

We then chain-linked interest costs, and restated things in USD terms. Tada — we can see how GIC performance looks against CPF funding costs:

So, using a mixture of actual market data, official numbers and a tiny bit of guesswork, it looks like the assets managed by GIC have outperformed the liabilities owed to CPF account holders and accrued by the government in funding the asset manager over the past twenty years. But the ‘mixed’ ten year record shows how gearing up a sovereign balance sheet to punt international financial assets isn’t exactly a slam dunk sleep-at-night trade.

Bottom line

The country’s epic bet of gearing up to buy financial assets pays dividends each year in the form of Net Investment Return Contributions. And these finance about 20 per cent of annual government current spending. Successfully taking investment risk has allowed Singapore to spend more on education, healthcare and other worthy things without hiking taxes.

So it’s easy to be shoulda-woulda-coulda-sniffy about the performance of a Singaporean sovereign wealth fund versus a simple passive index. And it’s easy to be a bit snarky about the edifice of vast financial leverage on which the whole Singaporean system appears to be built. But it looks like the bet has worked for them — and worked very, very well.