Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For three long decades, shorting Japanese government bonds was the go-to way for gaijin fund managers to lose their clients’ money and their own reputations. Hence the hard-to-shift moniker for the trade being the ultimate “widow-maker”.

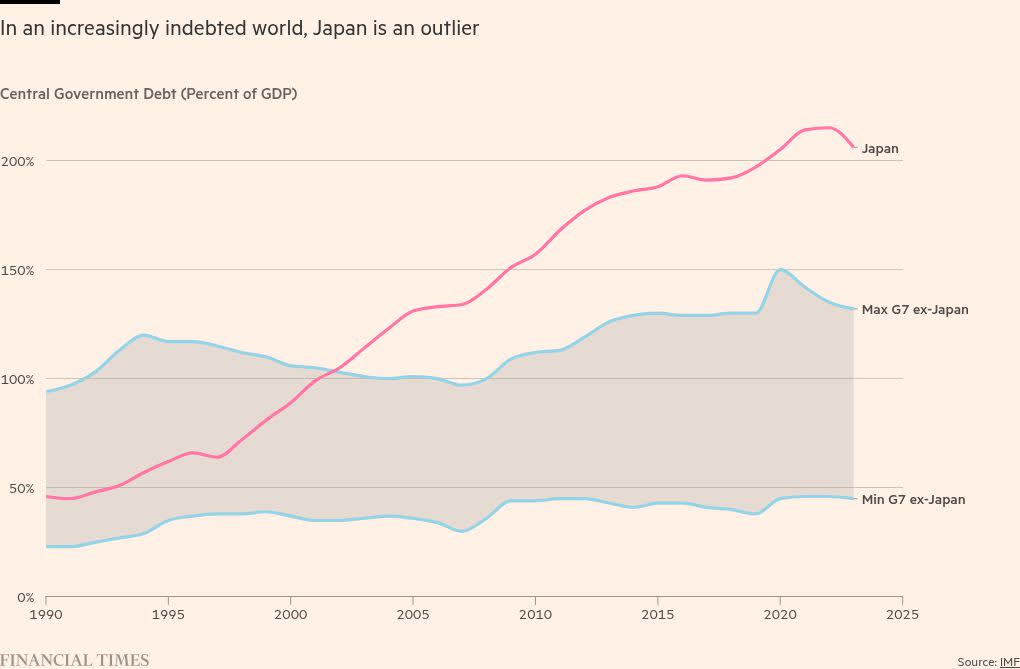

After all, the logic of the trade looked infallible. For an entire generation, Japanese government debt-to-GDP spiralled ever higher:

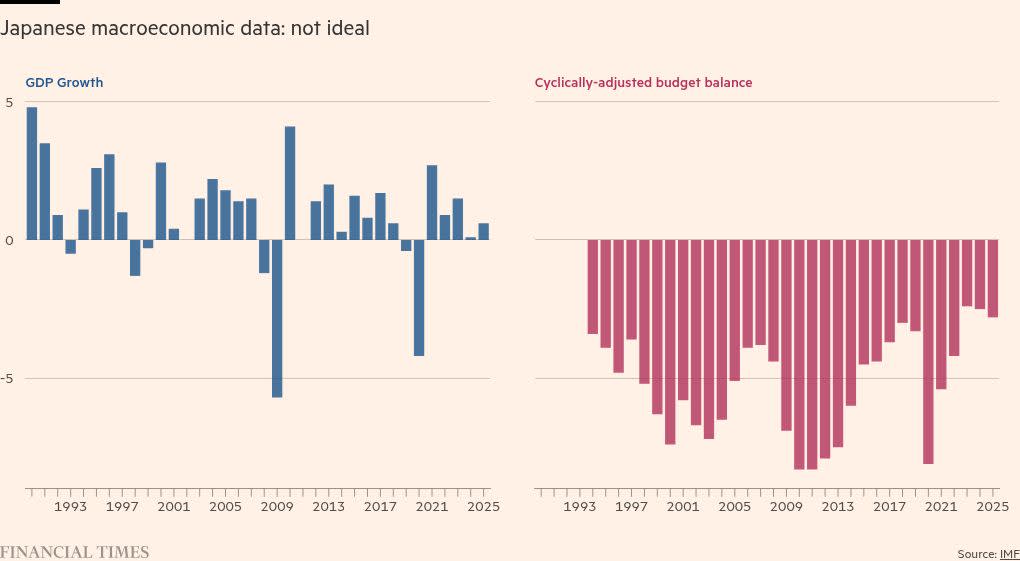

Meanwhile, GDP growth was persistently lacklustre and fiscal deficits were persistently gaping:

To many, debt looked unsustainable — or at least terribly bad value. And so managers were sucked into this losing trade year after year after year — either on a relative-to-benchmark basis, or as an outright short.

But as the past five years have shown, all those macro types who saw their careers ended by the trade prior weren’t entirely wrong — just wildly early.

As FTAV highlighted back in May, even in a world where long-dated bonds have generally traded poorly, price action at the long end of the Japanese government bond curve stands out as particularly flaccid.

Long-dated JGBs have now lost their holders vast amounts of money since 2020. And so those foreigners who have been long the widow-maker trade (that is, short superlong-JGBs) will have finally made out like bandits.

Will JGB trading reach the epic levels of flaccidity achieved by gilts under Liz Truss? This is, after all, the widow-maker dream. And Barclays’ analysts Shinichiro Kadota, Ayao Ehara, Moyeen Islam, Jack Meaning and Naohiko Baba think the question is at least worth asking, last week publishing a research report with the clickbait title “2022 gilt-style crisis for Japan?”

The authors note up front that despite a few similarities (a backdrop of rising yields, high debt, and prospectively weakening fiscal), there are also very important differences between gilts under Truss and JGBs today.

Specifically, Japan has a massive positive net international investment position totalling around 84 per cent of GDP (in contrast to the UK’s humungous net negative position); a large current account surplus worth 3-5 per cent of GDP each year (in contrast to the UK’s persistent deficits), and the JGB market “does not face the bloated leverage that LDI posed to the gilt market”.

And — as we’ve written more than once — this leverage was key to understanding what went on under Truss. While the Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget was the metaphorical match carelessly struck by politicians lacking the wherewithal to first check whether they might be standing in a room crammed with kegs of gunpowder, the match alone would not have been enough to burn down the gilt market absent said gunpowder.

But the Barclays note isn’t just another piece of evidence proving Betteridge’s Law. That’s because Barclays reckon that in the context of high government debt there are at least three reasons to be worried about the prospect of a gilt-crisis-style fiscal risk premium blowout in JGBs (despite the lack of LDI-style combustible accelerants).

First up:

. . . the JGB market faces a structural lack of superlong demand . . .

Issuing bonds into a part of the curve for which there is no longer demand is frankly stupid. But it’s also an easy thing to fix. If there are no longer natural buyers of superlong JGBs, the Ministry of Finance can just stop supplying superlongs and issue more shorter-term bonds instead.

To be fair, the authors do discuss how the JGB sell-off could eventually infect sub-10 year tenors as well, if Japan’s fiscal situation worsens further. So maybe our glib answer isn’t quite a silver bullet.

Second, the country has:

. . . no independent fiscal monitoring institutions, . . .

Alphaville is aware of the literature on how adopting fiscal rules reduces risk premia. And there’s bound to be work of which we’re not aware looking at the impact of introducing independent fiscal monitoring institutions like the OBR (comments box please 🙏).

We’re not convinced that establishing a new independent institution in Japan will be enough to tilt the scales between Truss-style-crisis and no-crisis, but what do we know. At least establishing such a body doesn’t look hard.

The authors note that there are a few candidate organisations in Japan, like the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy of Cabinet Office (reporting to the prime minister) and the Fiscal System Council of the Ministry of Finance (reporting to the finance minister) that could be made independent. Seems like an easy win.

Third, the market:

. . . is populated by volatility-averse domestic investors with increasing foreign participation.

Increasing foreign participation? The idea that the JGB market might be vulnerable to foreigners cutting their positions seems frankly weird. Because unlike the UK, the JGB market has not historically been dependent on the kindness of strangers. Aggregate foreign ownership sits at around 6 per cent.

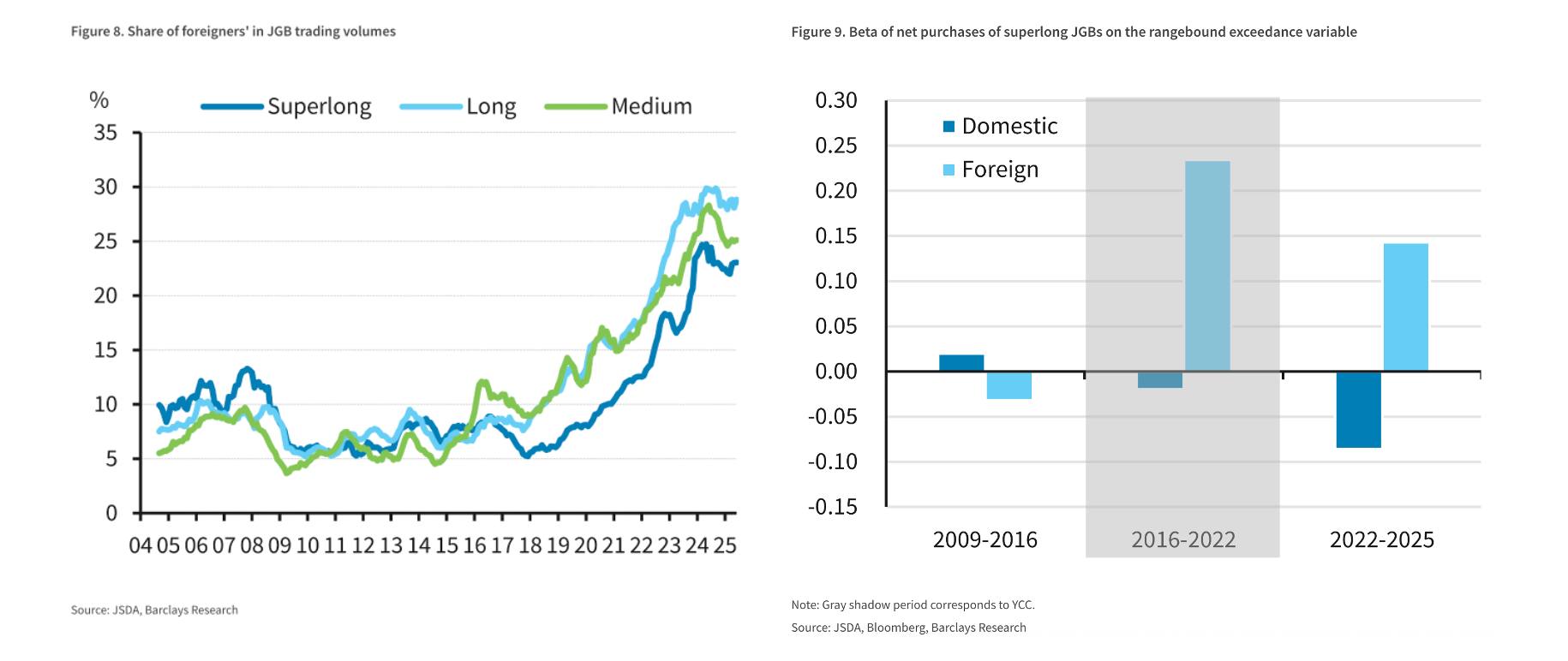

But Barclays points to data on trading volumes published by JSDA to show that even if foreign ownership of the total market is low, foreigners represent an increasingly large share of trading volumes at the long and superlong parts of the curve — between a fifth and a third.

Trading volumes are not the same as ownership statistics. Maybe foreigners are making an absolute mint by shorting the bejeesus out of 30 and 40 year JGBs, and this is showing up as high levels of foreigner trading in superlong JGBs?

Apparently not. Using some clever maths, Barclays analysis shows that:

. . . foreign investors tend to net-purchase superlong JGBs on large rates selloffs (defined as those exceeding the past 3m range), while domestic investors tend to be net sellers

In other words, it looks like ever since yields hit rock bottom, the gaijin trade has been long to buy each dip (in price) and go long superlong JGBs. And this increasing reliance on foreign interest is a crucial vulnerability in the Japanese government bond market.

It looks like there’s a new widow-maker trade in town.