Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Australian beef producers hope to prolong a boom in sales to the US after Donald Trump’s tariffs handed the country an advantage over rival exporters such as Brazil.

Cattle farmers feared the worst in April when the US president singled out Australia’s strict biosecurity laws for criticism and warned that the US would stop importing red meat from the Pacific country.

“I figured we were about to get railroaded,” said Adam Armstrong, a Queensland cattle farmer.

But Trump’s extensive new global tariff regime introduced last week imposed a relatively mild baseline duty of 10 per cent on Australia, which has an overall trade deficit with the US.

Other beef producers faced significantly higher levies, including 50 per cent for Brazil, 35 per cent for Canada and 15 per cent for New Zealand.

“What this decision means is that, in conjunction with the changes to other countries, Australian products are now more competitive going into the US,” Don Farrell, Australia’s trade minister, said.

US demand for Australian “trim” beef — which is blended with fattier American meat to make hamburger patties and mince — has boomed in recent years, as the American cattle industry has been unable to keep pace with consumption.

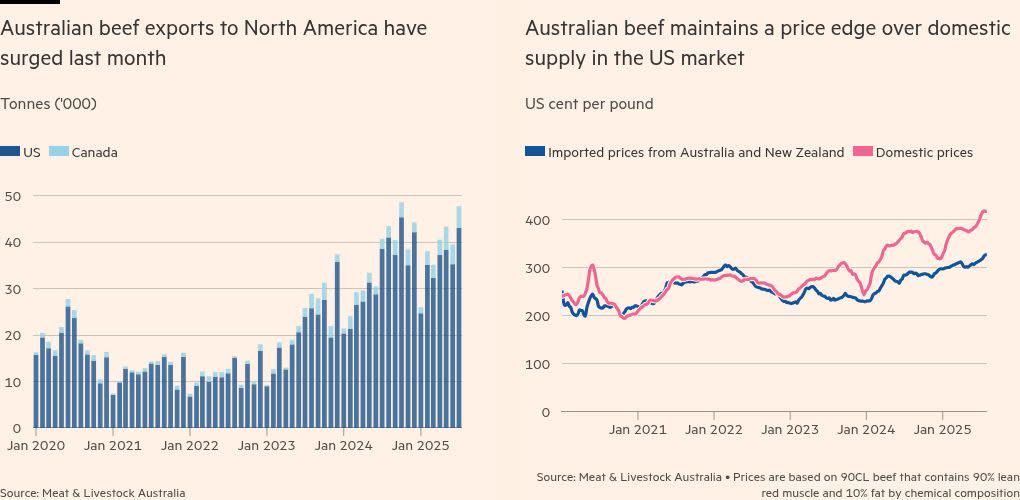

Exports of beef to the US rose 12 per cent in July on the year before to 43,000 tonnes, according to data from Meat & Livestock Australia, helping boost overall shipments last month to an all-time high.

Constrained domestic supply due to years of drought has driven US meat prices to record levels this year and further increased appetite for imports.

Australian exports to North America — including Canada, which has also imported more Australian beef — are up 30 per cent in 2025, and overall exports are up 11 per cent, according to MLA.

Will Evans, chief executive of Cattle Australia, a trade lobby, said the US was a “vital” partner, noting the country imported more than A$6bn (US$3.9bn) of beef last year.

Australia exports about 70 per cent of the beef it produces, according to the MLA. Prime cuts also go to markets including Japan, China and Europe.

Robert Mackenzie, a fifth-generation farmer in northern New South Wales with 3,500 Angus cattle, said the US industry could absorb the impact of the tariffs but that the product was “price driven”, which should play to Australia’s position.

“Higher tariffs for other countries that have made political waves have opened up bigger markets for Australia, not just [the] US but also China,” he said. “It’s made us more competitive.”

He said this had helped offset the impact of high energy and labour costs in Australia, where the industry also does not enjoy the subsidies offered in some other countries.

Yet Canberra’s move to lift restrictions on imports of cattle processed in the US but sourced from other countries — which were introduced in 2003 to prevent mad cow disease and other threats from infecting local herds — has stoked concern among farmers.

The Australian government denied it had compromised on its biosecurity regulations in service of a better trade deal with the US.

“The outcome of the technical assessment of beef from the United States is the culmination of a decade of science and risk-based import assessments and evaluations,” Farrell said in July.

Many cattle farmers remain cynical, pointing to the eleventh-hour announcement and alleging a lack of consultation with industry. They also fear that the country’s reputation for producing “clean, green, disease-free meat” could be jeopardised.

“It only takes one infected cow or infected piece of beef to spread the disease. Why would we take the risk?” said Mackenzie.

Armstrong cautioned that the beef industry was a “blood sport”, with frequent fluctuation between global winners and losers and no room for triumphalism.

“Brazil is in the line of fire and that bodes well for us,” he said. “But Trump could single us out for something else, so I’d be careful about celebrating.”