Greetings, Free Lunch readers. For the next few weeks, Tej will hold the fort here as we continue our Sundays-only summer schedule. I wish you all a relaxing northern hemisphere summer.

A week ago, the EU agreed a trade “deal” that it didn’t need with the US. Or at least their respective presidents did, according to the carefully worded explainer from Brussels. That explainer goes out of its way to point out this was a “political agreement” that is “not legally binding”. It is quite true, as the FT Editorial Board thunders, that the EU “capitulated” and gave Donald Trump his “dream scenario”. It might also be true that the Europeans could never have hoped for better terms, and that while they gave up the EU’s role as a defender of a rules-based order, they may at least have gained a bit of stability. (But don’t hold your breath.)

With the other “deals” and unilateral tariff changes now set for most of the US’s trading partners, will we get some peace? It is possible, but far from guaranteed, that the dust settles for a while, with Trump leaving the trade agenda quiet while pursuing other goals. In any case, it seems clear that US trade policy will not get any more liberal than this new status quo. So it is worth starting to think about how the new regime will reshape the global economy. Share your thoughts on freelunch@ft.com; below are mine.

What we are looking at is a world in which the US charges its consumers and businesses tariffs on imports from most of the world at rates from about 15 to 30 per cent. There are various sectoral and country exemptions and quotas, but that is the big picture: trade taxes are an order of magnitude greater than they have been for almost a century. Assuming something like this is here to stay (or gets worse), what will be the fallout? Here are four essential questions to ponder.

Will there be less trade?

Overall, probably yes. And with the US — in both directions — certainly. As I have explained before, the main effect of tariffs is not to change overall surpluses and deficits. Instead, it is to make all trade more expensive and shuffle activity between sectors and countries depending on the relative changes in trade costs. So we should expect altered supply chains with overall less trade.

There is, however, the possibility that the rest of the world reacts to Trump’s disruptive policy by doubling down on deepening trade integration between themselves. Already, most of the world is less exposed to trade with the US than the panicky response to Trump’s threats would suggest — so a decoupling from the US, combined with intensifying other trade networks, is certainly conceivable. (For a particularly, er, savoury example of strategies for dealing with US protectionism, my colleague Joel Suss has checked in on the Canadian maple syrup industry.)

There are obstacles to this, of course — the distrust between the EU and China seriously jeopardises even existing economic exchange between the blocs, let alone more integration. But elsewhere, trade deepening is within reach, certainly inside the EU single market and between the EU and friendly trading partners. So, it is quite possible that global trade integration will persist or even increase, even as the US’s share and absolute level of trade shrink radically.

Will global trade (im)balances change?

International trade flows are asymmetric. The EU, China, Japan and the big commodity exporters are large net surplus economies; the US, Canada and the UK run large external deficits. It can be hard to discern Trump’s goal, but it seems to include reducing the US’s negative trade balance. His policies are unlikely to achieve this, but what if he succeeds? Then it is arithmetically necessary that other countries’ external balances adjust as well.

If the US deficit is eliminated, either China or the EU or both must eliminate or at least run much smaller surpluses, since these are by far the biggest economies in the world and the numbers must add up to zero. How this might happen is perhaps the biggest macroeconomic conundrum we confront. The answer depends, in part, on which policy tools each economy is willing to use to affect the external balance and whether they are more powerful than those of a trading partner unwilling to adjust.

Michael Pettis, for example, has suggested that China’s more state-controlled economy has more influence, forcing market-based economies to adapt. The implication is that there is little the US can do to reduce the deficit unless China changes its policies. It also means the EU will be the victim of a rechanneling of Chinese exports from a US market closing towards Europe — a fear expressed by many EU policymakers and quantified by the European Central Bank. In Pettis’s words:

This shift would not occur because EU citizens, EU governments or the ECB wanted it to occur. It would be an automatic structural shift in the EU economy caused by an expansion in manufacturing that was engineered by Beijing for wholly domestic reasons and diverted away from the US economy by Washington, also for wholly domestic reasons.

I am sceptical: it seems to me that there are plenty of tools available for every economy to tilt the spending-versus-saving balance of its public, corporate or household sectors, which would tilt the external deficit as well. But that still raises two questions: first, will the big economic blocs in fact take the decisions required to change their external balances; and, second, what gives if their preferred choices are incompatible — if the US wants rid of its deficit but China and the EU want to maintain their surpluses?

How do economies restructure at home?

The irony is that both China and the EU have self-interested reasons to let their surpluses disappear and thereby accommodate Trump’s wish. For the EU, this is a matter of financing more investment inside the bloc rather than accumulating financial savings outside it. For China, it is an opportunity to vastly raise the prosperity and economic security of hundreds of millions of its citizens. But they will only do so if they better appreciate the link between the external position of the economy and the opportunities for restructuring at home.

What would a restructured EU economy look like? It would be one where the 3 per cent of economic production that is devoted to exports in excess of imports would instead be rechannelled into non-exportables — either infrastructure or services, or industrial goods that could be exported but won’t be, such as defence hardware. This could involve some painful sectoral reallocation, away from the German car industry in particular.

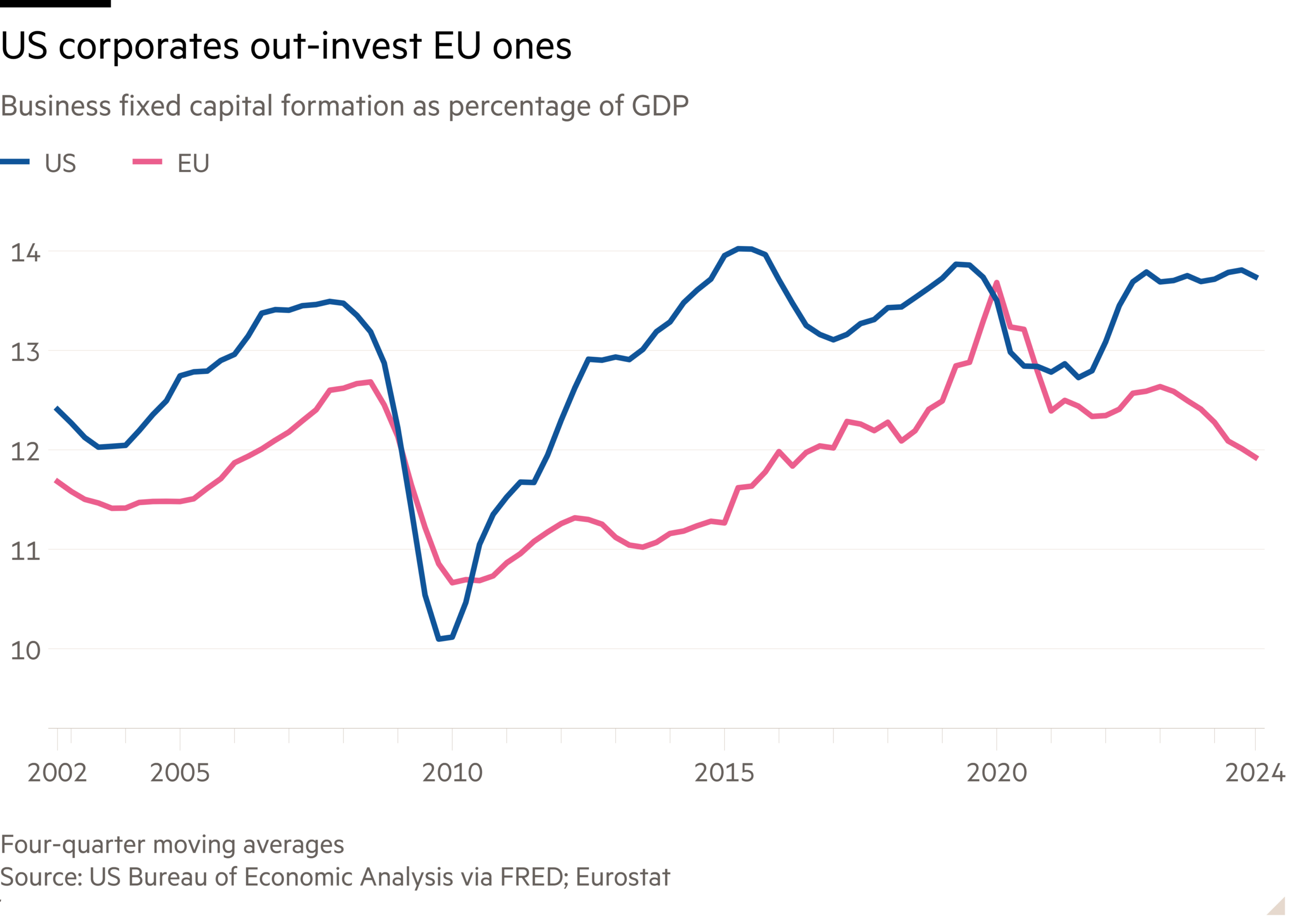

The US, too, would have to accept a domestic restructuring. As I have explained before, the deficit is what allows the US to out-invest Europe (see chart below). Paradoxically enough, Trump getting his way could involve US companies investing less and European ones investing more.

What happens to Chinese manufacturing?

In China, a sectoral reallocation would, in particular, involve greater consumption by households, which, given the country’s severe inequality, would bring a leap in economic wellbeing. Whether China’s elites have the stomach to give people the greater power and independence that comes with economic security, however, is doubtful.

A further question — of huge consequence to the entire world — is what would happen to manufacturing if China did engage in domestic rebalancing. My colleagues’ excellent Big Read article on Chinese manufacturing this week nails what is at stake. Huge policy support was put behind manufacturing expansion, in general as a way to restore demand growth that had collapsed with the real estate bubble, and more narrowly to make China a leader in green technology such as solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles. However, the result has been vanishing profit margins and falling productivity, even as production capacity has soared.

The conventional view is that manufacturing must be reined in by ending the excessive subsidy schemes. I am not convinced. It seems to me hard to argue there is overcapacity until every Chinese household has an electric car and a home with self-sufficient, storable, renewable electricity. But getting there would require the Chinese authorities to redirect subsidies to fuel domestic consumption. If it did, not only would it benefit its own citizens but ease the political economy of global macroeconomic relations.

All I have had to offer are questions more than answers. But if we are now going to live in Trump’s trading regime for the foreseeable future, these are the questions we need to ask.

Other readables

● In addition to capitulating to the US, Brussels proposed a new seven-year budget. Here is my take.

● As this FT Editorial points out, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy committed a terrible mistake in undermining the independence of his country’s anti-corruption agencies. Under domestic and foreign pressure, he has vowed to remedy the change, but a lot of damage has already been done. To understand who calls the shots in Zelenskyy’s office, read my colleague Chris Miller’s in-depth profile of his chief of staff Andriy Yermak.

● Paul Krugman analyses the economics of enshittification.

● It’s in the numbers: geopolitics increasingly shapes foreign direct investment decisions.

● The IMF has nudged up its growth forecast for the world economy.

● Minna Ålander asks some good questions about whether Nato’s new 5 per cent commitment to defence spending will do all that much good.