Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Armoured vehicles were lined up across the lawn of Dhaka’s premier arts institute, the Shilpakala Academy, when I visited in May. Soldiers had slung camp beds across the ground floor galleries of the fine arts department. The bronze and stone artworks that dot the sculpture garden were overshadowed by the army-green livery of the 1st East Bengal Regiment. It’s been like this since last year’s “monsoon revolution”, when former prime minister Sheikh Hasina ordered the army into the academy, as a base from which to crack down on protests over jobs across the Bangladeshi capital. After more than a thousand were killed in the unrest, Hasina resigned and fled the country. But, a year later, the soldiers are still there; Bangladesh has yet to return to normal.

The army shares the space with artists and curators tasked with rejuvenating the country’s arts scene. Amid uncertain political circumstances, they have begun to uncover a trove of 20th-century art few have ever seen.

The Shilpakala Academy’s then director of fine arts, Mustafa Zaman, took me round his basement storage unit. In one room, he pulled out trolleys bearing the close-stacked remnants of a unique — and little known — form of global modernism. There were daring abstract works by Murtaja Baseer, who studied in Florence and came of age in the febrile political climate of Dhaka during the run-up to the war that won Bangladesh its independence from Pakistan in 1971. There were huge but faint canvases by SM Sultan, whose deteriorating pigments marked out a highly stylised, richly symbolic record of Bengali rural life in the 20th century. And then there were a series of black-and-white ink sketches by Zainul Abedin, depicting the victims of a cyclone that struck what was then East Pakistan in 1970; their bold black lines still have a harrowing, virtuosic power.

They were also in terrible condition, never having been exhibited before. Thousands of important works belonging to state collections have languished for decades in institutional storehouses.

“All our master painters’ works were just dumped in storerooms, because our culture ministers never knew what their job was — they didn’t care,” said filmmaker Mostafa Sarwar Farooki, who now runs the culture ministry as part of economist and Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus’s interim government. “They didn’t know how to protect and preserve our cultural heritage.” Zaman agrees: “These people just wanted to please the national leader.”

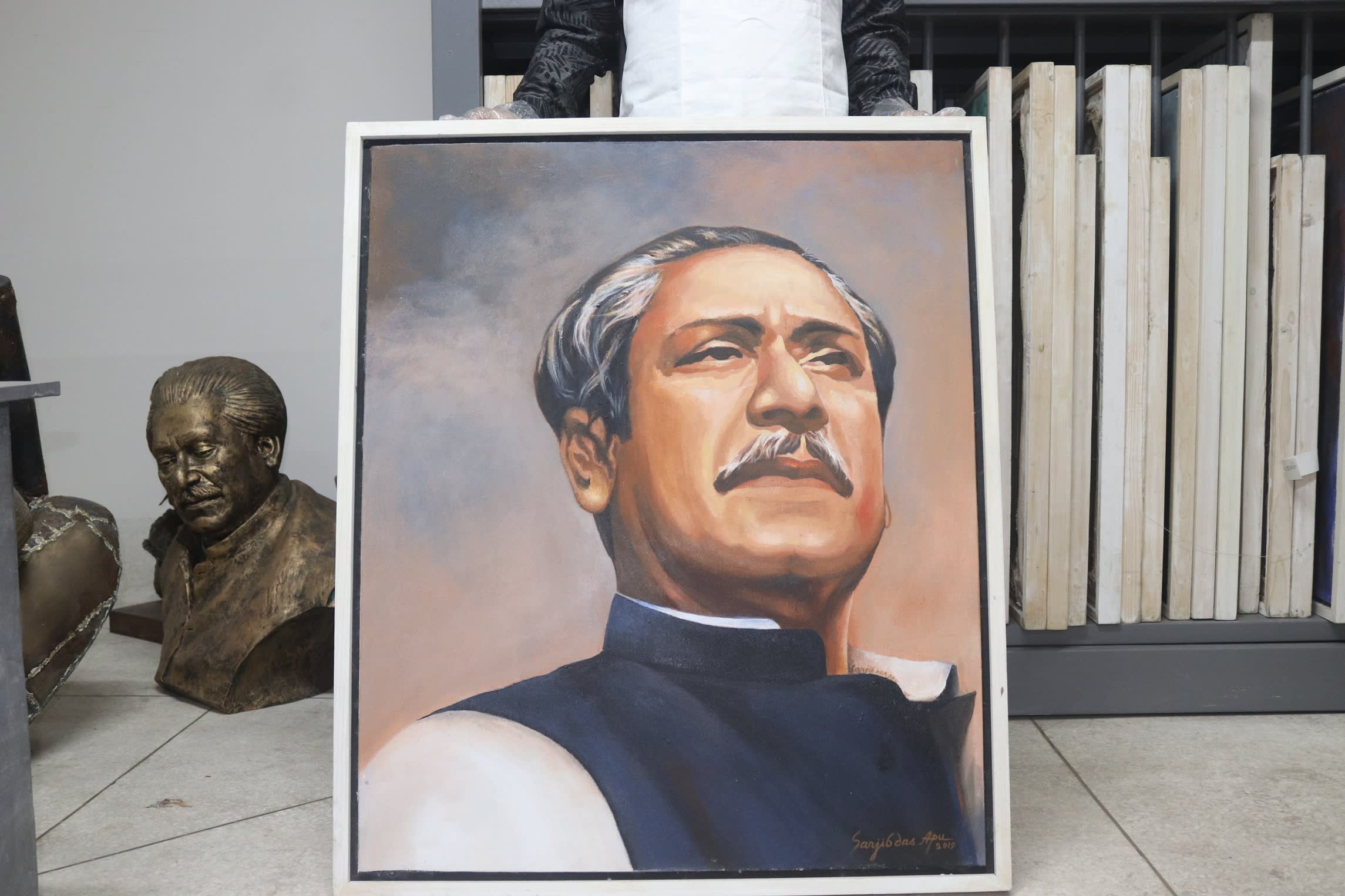

Over her 15 years in power, Hasina had fostered a cult of personality dedicated to the ruling family. Across Bangladesh, hundreds of millions of dollars were reportedly spent on statues and billboards of Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the country’s independence leader. Arts budgets were drained dry for years, Zaman told me. In another storage unit, I saw abandoned portraits of Hasina and her relatives, gathering dust like a fallen autocrat’s Terracotta Army.

The interim government has appointed the architect Marina Tabassum to take over the governing body of the National Museum: “We gave her a mandate and complete freedom to prepare a reform plan”, said Farooki, who will hold his position until Bangladesh holds elections next April. “Even if it takes years, whoever comes to power after us will have to see it through.”

Tabassum has a number of socially conscious architectural projects to her name, building emergency housing in the vast, impoverished Ganges delta. This year, she designed the Serpentine Pavilion in London’s Kensington Gardens, drawing on a tradition of Bengali canopies. She told me about her mission to overhaul Bangladesh’s approach to cultural heritage: “Our primary goal is to see how things are being kept,” she said. “The museums have such rich collections but they are not seen in public, because 90 per cent is kept in reserve.” She wants to put these paintings on permanent display, but, first, she said, “we need to find proper curation”.

It’s a daunting task: there has never been a comprehensive catalogue of the government’s art collection, nor any specialist curation or conservation. “Do these paintings actually exist?” wondered Bangladeshi collector Durjoy Rahman. “Or are they missing or completely damaged?” Several arts professionals told me they feared it might be too late to save some of these works, which have been stored for decades without air conditioning in the Dhaka humidity.

Meanwhile, there has been “significant market growth for Bangladeshi modern art”, according to Manjari Sihare-Sutin, head of Indian and South Asian art at Sotheby’s in New York. Last year, the auction house sold an ink work by Zainul Abedin from the series I saw at the Shilpakala for over £500,000, one of several works by the artist to have made six-figure sums in the last couple of years. That sort of valuation might encourage some to see Dhaka’s neglected storage units in a different light.

Perhaps the country’s foremost artist, Zainul Abedin was born near Dhaka in 1914, and trained in Kolkata during the dying days of British India. His most famous works date from the 1943 Bengal famine: ink sketches of the starving people he encountered every day on his way to work. The art school he founded in Dhaka after the Partition of India in 1947 absorbed disparate global influences, including cubist-inflected social realism, nascent abstract expressionism, and Japanese print-making.

Today, Abedin’s designs adorn Bangladeshi banknotes, but his work is on public display in just one room in Dhaka. His often socially conscious work sat uncomfortably with Hasina’s jingoistic, dynastic brand of nationalism. “We were always afraid of her attitude towards my father’s work,” said Abedin’s son Mainul, who lives in his father’s old house, its walls lined with canvases of half-a-century ago.

Now Tabassum says her job is made easier because there is finally the political will to show off modern art. No one can say how long that will last. The walls of government offices still bear the pale white imprints where portraits of Hasina and her father had hung before last year’s uprising.

Nevertheless, Tabassum is determined: “It’s our identity, and we have to preserve it before it’s lost.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning