Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Here are two contrasting facts about Japan. Number one: the yield on 30-year government bonds hit an all-time high of 3.21 per cent earlier this month after a series of weak auctions — a sign, perhaps, that markets are finally becoming concerned about the country’s enormous public debt. Number two: according to Morgan Stanley, Japan’s budget deficit was almost completely eliminated in the first quarter of this year, putting the public finances in their best position for almost three decades.

Which of these is signal and which is noise? Is it a moment for alarm or for optimism about Japan’s finances? A bad election result for the ruling Liberal Democratic party this month, which raises the odds of spendthrift, populist governance, seems like a good reason for markets to worry. But the remarkable and little-appreciated transformation in Japan’s economy since the pandemic makes the second fact more relevant: after decades when it was trapped in a deflationary equilibrium, Japan is on its way to a new regime. Managing the public finances of an elderly, low-growth country will always be difficult, but Japan’s position is no longer obviously worse than Italy, France or the UK, and its immediate fiscal trajectory looks quite a lot healthier than the US. It is quite a turnaround.

To make sense of the shift, consider Japan’s situation during the so-called “lost decades” after its bubble burst in 1990. The country suffered from chronically weak demand. Corporates and households both sought to save rather than spend. Prices were in deflation or thereabouts; interest rates were stuck at zero. Wages were flat. To keep unemployment down and the economy afloat, Japan’s government acted as the spender of last resort, stepping in with regular stimulus packages, running persistent deficits that cumulated into a large debt, all without ever doing enough to break free from the deflationary trap. (China’s situation today is somewhat similar.)

The so-called Abenomics stimulus, following the election of prime minister Shinzo Abe in 2012, began to change this, but in the end it was Covid and the associated global inflation that made the difference. Prices have risen faster than the Bank of Japan’s 2 per cent goal for the past three years; interest rates, at 0.5 per cent, are off the lower limit of zero; and wages are rising. This return to nominal growth in wages and prices has led to an immediate rise in revenues from income and consumption taxes, which is what has brought the public finances back into balance.

This transformation has been painful for the Japanese public because it is unfinished. The inflation shock came from outside, rather than within, and so wages have not kept up with prices, resulting in falling real incomes. Expressed in terms of financial balances, a decline in the government deficit has been offset by lower household savings, while the corporate sector continues to run a surplus. The final, badly needed change is to drive wages higher. It makes sense, therefore, to seek a hot labour market and raise interest rates only slowly, not least because the international environment is ominous, with Japan badly exposed to competition from China and tariffs in the US.

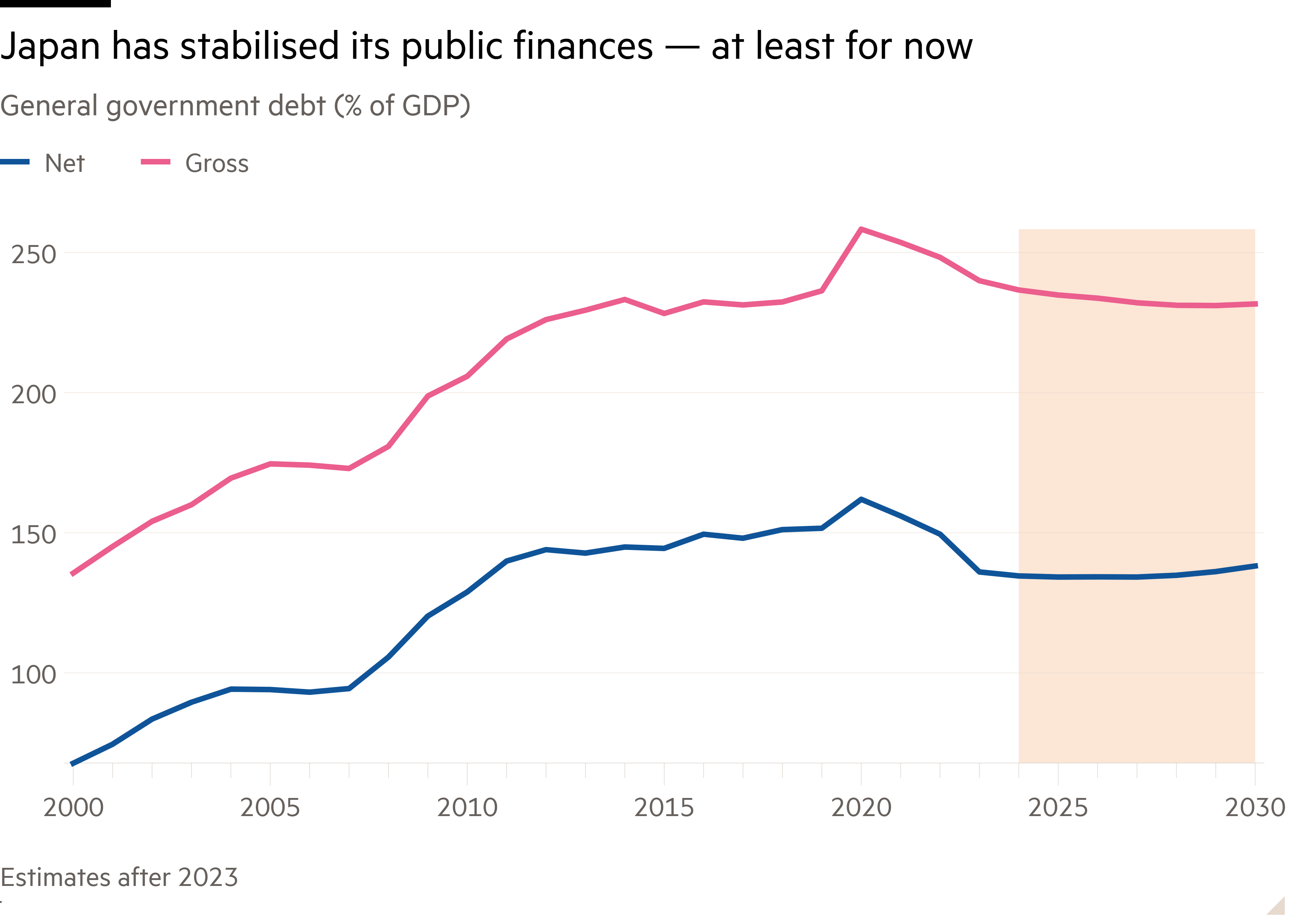

Nominal growth opens up a window during which it is possible to bring down debt. Indeed, gross debt has already fallen from a peak of 258 per cent of GDP in 2020 to 235 per cent this year, according to the IMF. Price rises have an almost instant effect on tax revenues, whereas it takes years for existing debt to roll off and refinance at higher interest rates, so there is a one-time benefit from moving to a regime with inflation.

This window will not last for ever. It would therefore be unwise to squander it with tax giveaways or new spending pledges, other than, perhaps, some short-term relief for overstretched households. While deflation continued, stimulus made sense in order to escape it; now that inflation is back, fiscal discipline must return as well. Politicians may find the changeover uncomfortable.

Nor does the return of inflation solve the deeper problem of growth in Japan’s economy. It never could, by itself. Expanding a heavily regulated economy with an ageing, declining population is an exceptionally hard challenge, and one Japan shares with Europe. But healthy demand makes it easier to try. A tight labour market with rising prices is a better environment in which to risk starting a new business, to reform rigid employment protections or to borrow money in order to invest.

What of the rise in 30-year bond yields? There is a plausible technical explanation, which is that Japanese insurance companies have already bought enough long-dated debt to match their liabilities, and the government is issuing too much of it. An argument to be sanguine is the lesser increase in 10-year yields. They now stand at 1.57 per cent, which does not imply an enormous risk premium for holding Japanese paper, although nor does it encourage further borrowing.

Abe, the prime minister whose stimulus set the current changes in motion, was gunned down in 2022 by a man with a grudge against a religious cult. To tackle Japan’s endlessly rising debt by first ending deflation was always an explicit goal of his policies. Politically, his stimulus was the easy part, and quite naturally, nobody will appreciate it while incomes are still rising slower than prices. The turnaround in Japan’s public finance is, nonetheless, a vindication.