Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A few weeks ago, I had one of those “blink” moments that changed my view of the labour market in America. I was in a shipbuilding factory in Marinette, Wisconsin, owned by the Italian company Fincantieri. Among other things they build giant frigates for the US Navy, vessels that are more than 400-feet long and many stories high.

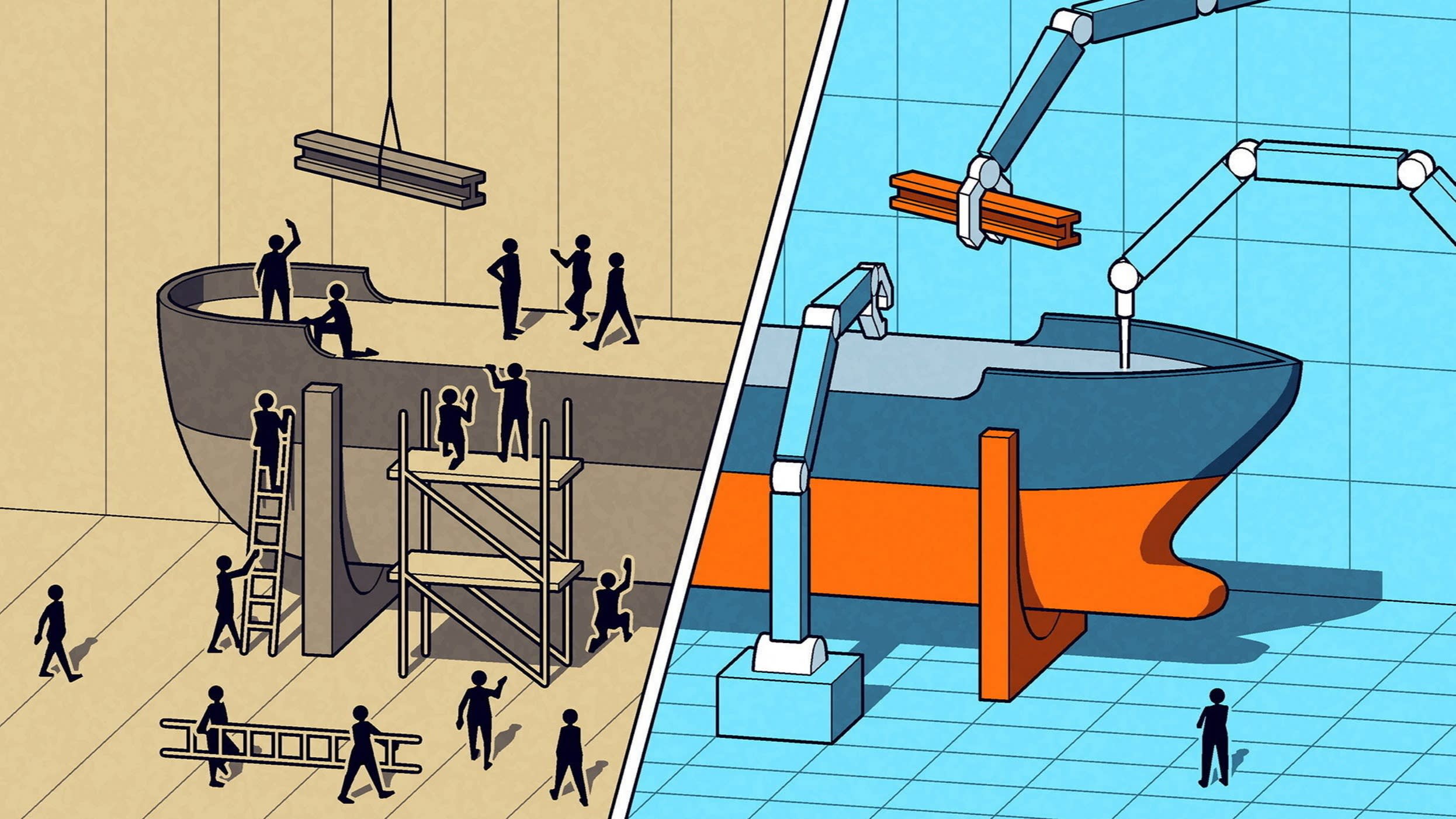

It used to take hundreds of men years to do the kind of metal bending this takes. But in this massive building, a little more than the size of a football field, I counted fewer than two dozen workers. They were directing robotic welding arms to carve massive pieces of steel in a fraction of the time that hand blasting takes. Virtual reality helmets helped them to exactly match construction on new builds to parts yet to be fitted, something that used to involve guesswork and paper blueprints. Even painters were wearing sci-fi type “exosuits” (think Matt Damon in Elysium) to make their jobs exponentially easier and more comfortable.

If this is what’s happening in shipbuilding, one of the more antiquated industries around, think about the potential of technology to change the industrial workplace over the next few years. We already know that it has had a greater impact on manufacturing jobs than even outsourcing to China did. The two factors have together radically transformed the employment map of the US. In 1990, manufacturing was the biggest employer in most states. Today, it’s top only in Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, Alabama, Kentucky and my own home state of Indiana.

The latest jobs figures from June show manufacturing employment as flat, despite all the president’s talk about reshoring. While some of this might be about tariffs, I think it’s more about the changing nature of industrial employment. Factory jobs are fewer, but much better than they used to be when I was hanging out in the crowded, relatively low-tech electronic component facilities my father ran decades ago for companies such as United Technologies.

The employees I met in Marinette were working more at the level of engineers than machinists. They were involved in product innovation, research and the training of new workers, something that is transformed by technology — it now takes days rather than months to get a new welder up to speed using robotic equipment.

But it also takes investment, and that’s something not every company has been willing or able to make. Fincantieri poured almost a billion dollars in capex into its Wisconsin facilities over 15 years, and the long-term security of defence contracts (which extend over years or even decades) have made that a good bet. The company now employs 2,500 people in a town of roughly 11,000, with a large multiplier effect. For every Fincantieri job in the region, eight others are supported in areas like the company’s supply chain, housing and construction, services and the public sector.

This kind of technology deployment is not present in every shipbuilding business, or indeed in most industrial companies. There is a superstar effect in terms of technology investment in manufacturing, which tends to be concentrated among standout businesses, and in particular industries — the automotive sector is highly automated, for example, while areas such as food production, mining and textiles are less so.

Greater dissemination of technology across industries and companies of all sizes is crucial because tech-based productivity increases are the only way for the manufacturing sector in a country such as the US to compete with China or other nations that have cheaper labour costs.

While building ships or chips or even cars in the US isn’t going to replace the jobs of the 1990s, it’s important to keep a healthy level of industrial production in large regionalised economies (the Americas, Europe and China would all fit that description) for national security and resiliency. Supply chain disruptions happen for all kinds of reasons, and the world shouldn’t put all its eggs in one basket.

That said, the changing nature and number of manufacturing jobs raises important questions about where labour market growth will come from. In the US, healthcare has replaced manufacturing over the last three decades as the top employer in most states. Some of this is down to the fact that Americans are getting older and richer and spending more on medical treatment. Some of it is because they are fatter and less healthy than they should be and have a highly inefficient and fragmented healthcare industry that incentivises expensive procedures and medications rather than prevention. And some of it is down to the fact that healthcare can’t, in most cases, be outsourced.

But an increasing number of healthcare jobs can be improved or even replaced by technology. And here, changes in the manufacturing sector provide a window into what is coming down the pike for America’s fastest growing industry. Healthcare costs in the US are high and growing faster than overall inflation. Service quality is quite mixed, and workers are both in short supply and less well trained than they should be. Technology penetration is low.

My guess is that this will present an opportunity for artificial intelligence. Doctors may be the shipbuilders of the future, in a labour market that will be defined — as it always has been — by technology disruption.