Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what Trump’s second term means for Washington, business and the world

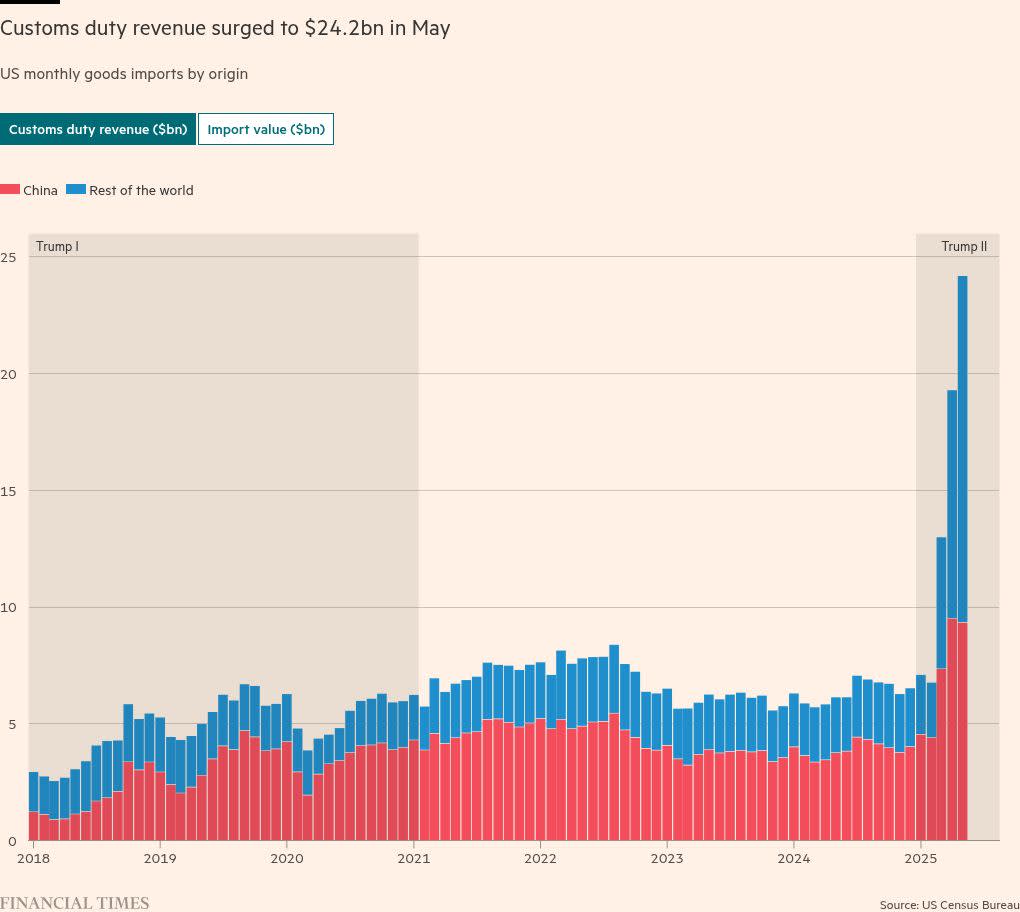

US tariff revenues surged almost fourfold from a year earlier to a record $24.2bn in May, the first full month in which President Donald Trump’s 10 per cent global tariff was in effect.

The figure represented a rise of more than 25 per cent from the month earlier, while the total value of US goods imports remained broadly unchanged from April.

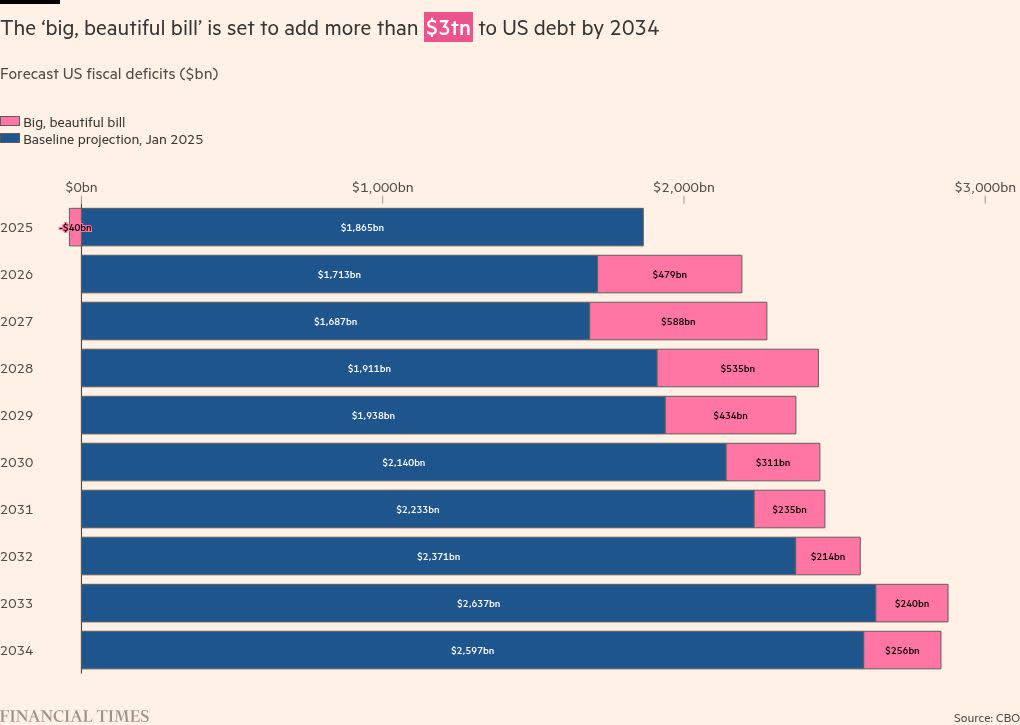

The figures suggest Trump’s trade war could provide a much-needed boost to the US government’s coffers and comes as Republicans in Congress close in on passing the president’s flagship tax and spending bill.

The bill, which extends vast tax cuts from Trump’s first administration but makes steep cuts to public healthcare for low-income Americans, is forecast to add $3.4tn to the US government deficit over the next decade.

But the data also underscored the potential for Trump’s aggressive tariff increases to distort global trade flows.

Imports to the US from China fell to $19.3bn, a 21 per cent drop from the previous month and 43 per cent down from the same month in 2024, reflecting a significant decline in trade between the world’s two largest economies.

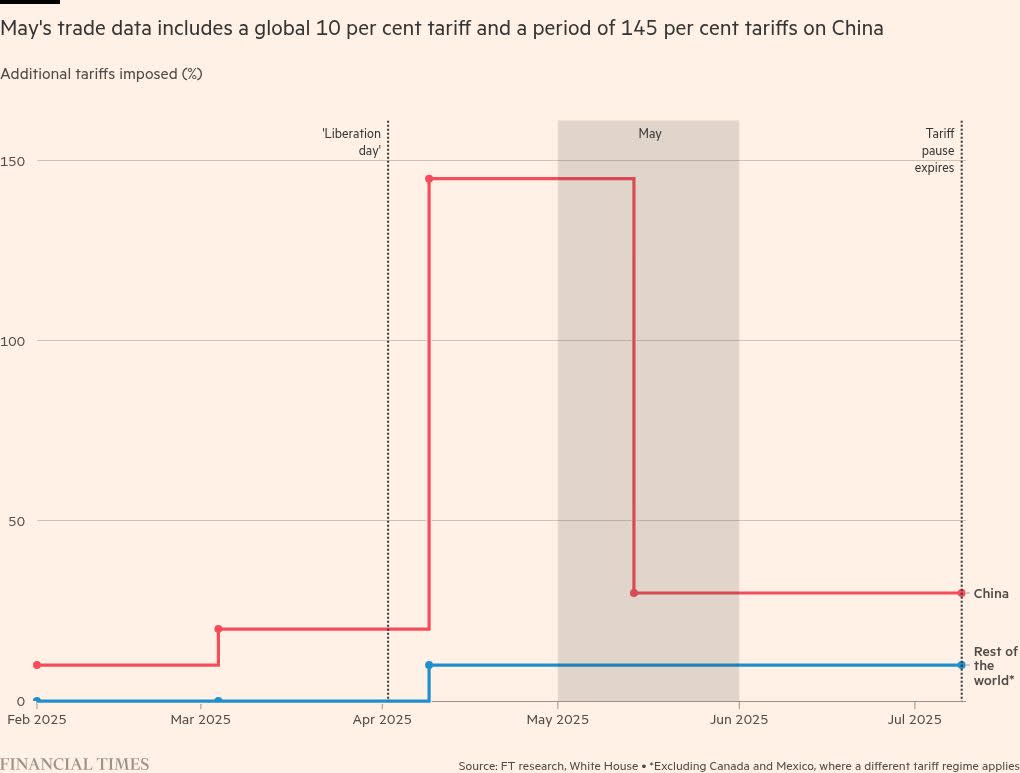

Earlier this year, Trump imposed new tariffs of 145 per cent on all Chinese goods before cutting the rate to 30 per cent after US officials held talks with their Chinese counterparts in London and Geneva.

The slump in trade brought Chinese imports destined for domestic consumption to their lowest level in 19 years.

The US leader has particularly targeted China as he seeks to reshape global trade, saying both that he wants to bring manufacturing back to the US and that the levies will raise money and make the country “very rich”.

Trump has insisted the revenues raised from tariffs can reduce reliance on income taxes. But despite the rise in sums collected, the receipts represented only about 7.7 per cent of May’s federal deficit of $316bn.

The deficit figure oscillates from month to month, however. The sum raised in May was equivalent to about 14.5 per cent of the typical $166bn shortfall between federal spending and revenues over the past year.

Despite singling out China for the steepest tariffs, Trump triggered a global stock market rout with April’s so-called liberation day, when he unleashed tariffs of 10 per cent to 50 per cent on most US trading partners, before later temporarily lowering them to 10 per cent for 90 days.

Since April 9, a baseline rate of 10 per cent has been applied on almost all goods imports. Certain products, including pharmaceuticals and semiconductors, are exempted but may face a separate tariff in future, while steel, aluminium and automobiles are charged a higher rate of 25 per cent to 50 per cent.

If the 90-day pause expires as planned on July 9, the US is set to increase tariffs on dozens of countries without special agreements. Trump has threatened the EU with a 50 per cent levy if a deal is not reached, while Vietnam has successfully negotiated a 20 per cent rate, down from the original 46 per cent the US had threatened to impose.

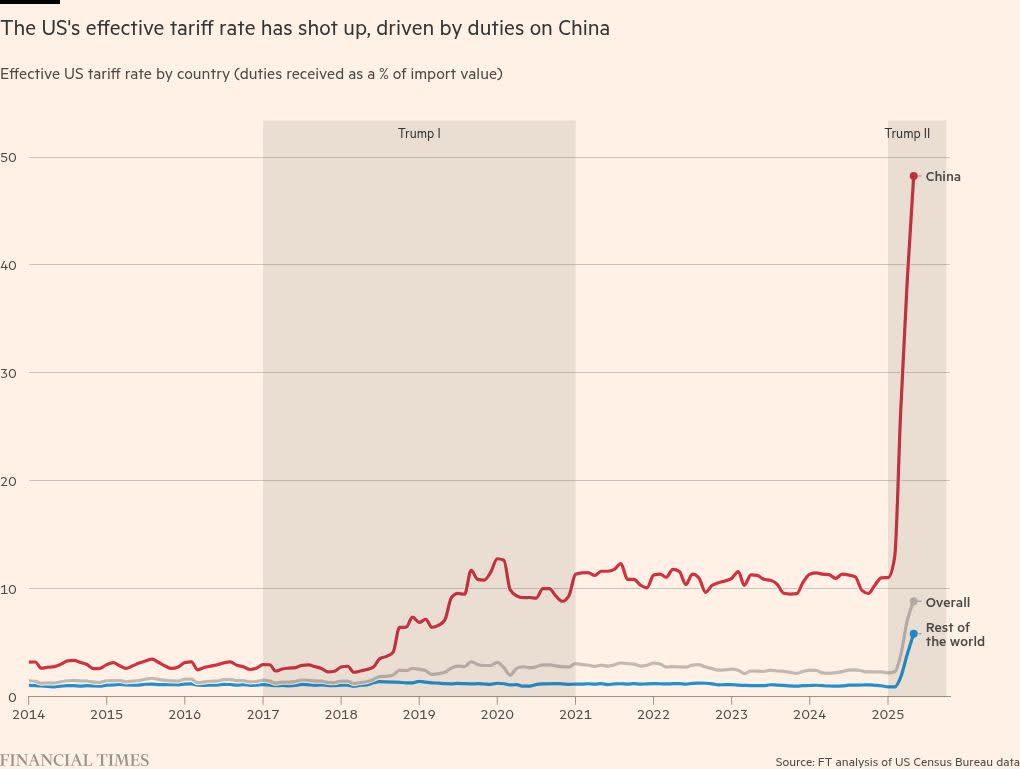

The effective tariff rate, calculated as the average duty raised across all imports as a share of their value, increased to 8.8 per cent in May, its highest figure since 1946. For Chinese goods, the tariff rate reached a record 48 per cent.

At the end of May, the US doubled steel and aluminium tariffs to 50 per cent and later expanded its definition to include steel derivative products such as freezers, dishwashers and washing machines.

Analysis by Yale Budget Lab suggests that if the rates in place as of June 16 were to remain, with no further increase on July 9, the effective tariff rate would settle at about 15 per cent, even after accounting for changes in consumer behaviour.

Taking into account various effects of the tariffs on the US economy, the think-tank projected that the current tariff policy would raise $2.2tn between 2025 and 2034, but thanks to reductions in tax revenue streams elsewhere, would result in net revenues of $1.8tn during those years.

Although a large sum, it is significantly less than the $3.2tn forecast to be added to US federal debt over the same period by implementing Trump’s tax bill, according to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office.

Additional reporting by Aime Williams in Washington